Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 viewsChapter Four: Project Financing

Chapter Four: Project Financing

Uploaded by

Endashew AlemuProject financing involves raising long-term debt for major projects based on the cash flow from the project rather than the balance sheets of sponsors. It is commonly used for large infrastructure and resource extraction projects. Key characteristics include non-recourse or limited-recourse debt, high leverage through mostly debt financing, and lenders relying on projected cash flows from contracts/licenses rather than asset values. Project financing provides benefits to investors such as limiting liability, improving returns through leverage, obtaining tax benefits, and potentially keeping debt off balance sheets.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- FR - MID - TERM - TEST - 2020 CPA Financial ReportingDocument13 pagesFR - MID - TERM - TEST - 2020 CPA Financial ReportingH M Yasir MuyidNo ratings yet

- FOF Tutorial 9 AnsDocument6 pagesFOF Tutorial 9 AnsYasmin Zainuddin100% (1)

- Pizza Hut Corporation Has Decided To Enter The Catering BusinessDocument2 pagesPizza Hut Corporation Has Decided To Enter The Catering Businesstrilocksp Singh0% (1)

- Credtrans Activity CasesDocument5 pagesCredtrans Activity CasesChaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Project Finance - A Guide For Contractors and EngineersDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Project Finance - A Guide For Contractors and Engineershazemdiab100% (1)

- Project Financing... NotesDocument21 pagesProject Financing... NotesRoney Raju Philip75% (4)

- Why Do Sponsors Use Project Finance?: 2. How Does Project Finance Create Value? Justify With An ExampleDocument3 pagesWhy Do Sponsors Use Project Finance?: 2. How Does Project Finance Create Value? Justify With An Examplekumsisa kajelchaNo ratings yet

- Unit-6:-Project FinanceDocument2 pagesUnit-6:-Project FinanceShradha KapseNo ratings yet

- Project Report - Project FinanceDocument10 pagesProject Report - Project Financeanon_266246835No ratings yet

- CH 7 Project FinancingDocument37 pagesCH 7 Project Financingyimer50% (2)

- Project FinanceDocument10 pagesProject FinanceElj LabNo ratings yet

- Arc612 Group 9Document33 pagesArc612 Group 9Stephen OlufekoNo ratings yet

- System of Project FinancingDocument13 pagesSystem of Project Financingmmaannttrraa100% (1)

- PDI Complete SlidesDocument151 pagesPDI Complete SlidesAbrar AkmalNo ratings yet

- Module 2: Financing of ProjectsDocument24 pagesModule 2: Financing of Projectsmy VinayNo ratings yet

- Project Finance: PURPA, The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act of 1978. Originally Envisioned AsDocument68 pagesProject Finance: PURPA, The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act of 1978. Originally Envisioned Assun_ashwiniNo ratings yet

- Features: Graham D Vinter, Project Finance, 3 Edition, 2006, Page No.1Document9 pagesFeatures: Graham D Vinter, Project Finance, 3 Edition, 2006, Page No.1ayush gattaniNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Project FinancingDocument2 pagesAdvantages of Project FinancingCultural RepresentativesNo ratings yet

- Project Finance AdvantagesDocument8 pagesProject Finance AdvantagesmaheshNo ratings yet

- Aydemir 2006Document128 pagesAydemir 2006Ankit SuriNo ratings yet

- Project FinancingDocument15 pagesProject FinancingAnkush RatnaparkheNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amDocument23 pagesLecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amSyeda Maira Batool100% (1)

- Financing of ProjectDocument13 pagesFinancing of ProjectADITYA SATAPATHYNo ratings yet

- Project Finance & Loan Syndication..EveningDocument21 pagesProject Finance & Loan Syndication..EveningRabina Akter JotyNo ratings yet

- Motivation For Project FinancingDocument15 pagesMotivation For Project FinancinghassanNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes - Intro - Stakeholders - SPVDocument20 pagesLecture Notes - Intro - Stakeholders - SPVHimanshu DuttaNo ratings yet

- Procurement Guide: CHP Financing: 1. OverviewDocument9 pagesProcurement Guide: CHP Financing: 1. OverviewCarlos LinaresNo ratings yet

- Project FinanceDocument128 pagesProject FinanceSantosh Kumar100% (2)

- Chapter 8 The Financing DecisionDocument38 pagesChapter 8 The Financing DecisionAllene MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Project Finance-WPS OfficeDocument12 pagesProject Finance-WPS OfficeLAKHAN TRIVEDINo ratings yet

- What Is Project Financing?: Corporate LoansDocument6 pagesWhat Is Project Financing?: Corporate LoansRam KiranNo ratings yet

- Project Finance: Professor Pierre HillionDocument72 pagesProject Finance: Professor Pierre Hillionnirupma86No ratings yet

- The Advantages-Disadvantages of Project FinancingDocument4 pagesThe Advantages-Disadvantages of Project FinancingBhagyashree Mohite67% (3)

- Lecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 01012022 063406pm 1 18062022 052305pmDocument22 pagesLecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 01012022 063406pm 1 18062022 052305pmSyeda Maira BatoolNo ratings yet

- 1 Pre Read For Introductions To Project FinancingDocument4 pages1 Pre Read For Introductions To Project FinancingChanchal MisraNo ratings yet

- 2017 2018 Eup 222 Sem 1 Project Finance Topic Outcome 1Document32 pages2017 2018 Eup 222 Sem 1 Project Finance Topic Outcome 1NNadiah IsaNo ratings yet

- What Is Project Finance: As Secondary SecurityDocument8 pagesWhat Is Project Finance: As Secondary SecuritySURAJ TALEKARNo ratings yet

- Project FinanceDocument33 pagesProject Financeatharva.bhakre2005No ratings yet

- Project FinancingDocument4 pagesProject FinancingRishabh JainNo ratings yet

- Bpe 34603 - LN 5 25 March 2019Document28 pagesBpe 34603 - LN 5 25 March 2019Irfan AzmanNo ratings yet

- Project Finance: Professor Pierre HillionDocument72 pagesProject Finance: Professor Pierre Hillionzhongyi87No ratings yet

- 403 All UnitsDocument73 pages403 All Units505 Akanksha TiwariNo ratings yet

- Project Financing in India (Module 7) 37Document62 pagesProject Financing in India (Module 7) 37Shazma KhanNo ratings yet

- CAC Tutorial 11Document4 pagesCAC Tutorial 11zachariaseNo ratings yet

- Source of Finance: Management Education CentreDocument20 pagesSource of Finance: Management Education CentredeepakjainbokariaNo ratings yet

- SEBI Guidelines & Institutional Consideration For Project FinanceDocument21 pagesSEBI Guidelines & Institutional Consideration For Project FinanceSachin ShintreNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Capital BudgetingDocument15 pagesChapter 6 Capital Budgetingmddev87No ratings yet

- Methods of Project Finance White Paper White Paper: Why Is It Important To Understand Project Finance?Document18 pagesMethods of Project Finance White Paper White Paper: Why Is It Important To Understand Project Finance?nfkrecNo ratings yet

- Project Management For Construction - Financing of Constructed FacilitiesDocument22 pagesProject Management For Construction - Financing of Constructed Facilitieskingston roseNo ratings yet

- Types of Projects: Project FinancingDocument9 pagesTypes of Projects: Project Financingshandilya-saroj-24No ratings yet

- PFDocument16 pagesPFadabotor7No ratings yet

- Cursul 1 - Introducere in Finantarea ProiectelorDocument27 pagesCursul 1 - Introducere in Finantarea ProiectelorAna-Maria IonescuNo ratings yet

- Project Finance - How It Works, Definition, and Types of LoansDocument7 pagesProject Finance - How It Works, Definition, and Types of LoansP H O E N I XNo ratings yet

- Project FinanceDocument37 pagesProject FinanceFarhana DibagelenNo ratings yet

- Project Finance and Loan Syndication ProceduresDocument28 pagesProject Finance and Loan Syndication ProceduresKeerthi ThulasiNo ratings yet

- Project Financing-Lenders PerspectiveDocument26 pagesProject Financing-Lenders PerspectiveUsman Aziz Khan100% (1)

- Introduction To Project FinancingDocument88 pagesIntroduction To Project FinancingE B100% (1)

- Project FinanceDocument9 pagesProject FinanceLAZY TWEETYNo ratings yet

- PP1Document7 pagesPP1yaminiNo ratings yet

- Project FinancingDocument29 pagesProject FinancingFirehun AlemuNo ratings yet

- Financing and Investment Trends: Subtittle If Needed. If Not MONTH 2018Document32 pagesFinancing and Investment Trends: Subtittle If Needed. If Not MONTH 2018Mihai BalanNo ratings yet

- B.vinod KumarDocument42 pagesB.vinod Kumarmrcopy xeroxNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet - ConsolidatedDocument239 pagesBalance Sheet - ConsolidatedAISHWARYA KUZHIKKATNo ratings yet

- MCQ - Accounting Cycle (ACCT 642 - G1, 2, 4)Document4 pagesMCQ - Accounting Cycle (ACCT 642 - G1, 2, 4)lamslamNo ratings yet

- IAS 1 - Presentation of Financial StatementsDocument17 pagesIAS 1 - Presentation of Financial StatementsMạnh hưng LêNo ratings yet

- Chinkee Tan-LearningsDocument2 pagesChinkee Tan-LearningsjomarvaldezconabacaniNo ratings yet

- FABM 2 HANDOUTS 1st QRTRDocument17 pagesFABM 2 HANDOUTS 1st QRTRDanise PorrasNo ratings yet

- Multi-Class Text Classification With Scikit-LearnDocument20 pagesMulti-Class Text Classification With Scikit-LearnmohitNo ratings yet

- 03 Ch10 Managing Working CapitalDocument41 pages03 Ch10 Managing Working CapitalArnold LuayonNo ratings yet

- Fin 533Document14 pagesFin 533Can ManNo ratings yet

- Example of A Valid Auto-Contract: If The Agent Has Been Empowered To Borrow Money, He May Himself Be The Lender atDocument9 pagesExample of A Valid Auto-Contract: If The Agent Has Been Empowered To Borrow Money, He May Himself Be The Lender atDwight BlezaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document5 pagesChapter 11张心怡No ratings yet

- Unified Directives 2076 Amendment1 PDFDocument74 pagesUnified Directives 2076 Amendment1 PDFRupEshNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Homework Lisa ChandlerDocument13 pagesWeek 7 Homework Lisa ChandlerShopno ChuraNo ratings yet

- Factoring AgreementDocument17 pagesFactoring Agreementfra.spNo ratings yet

- 6809 Accounts ReceivableDocument2 pages6809 Accounts ReceivableEsse Valdez0% (1)

- RATIO ANALYSIS MCQsDocument9 pagesRATIO ANALYSIS MCQsAS GamingNo ratings yet

- 15P35H0256Document91 pages15P35H0256Manoj JainNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Statement of Financial Position Balance SheetDocument24 pagesWeek 1 Statement of Financial Position Balance SheetCamille ReyesNo ratings yet

- Maximum Mark: 80: Cambridge Ordinary LevelDocument12 pagesMaximum Mark: 80: Cambridge Ordinary LevelSyed AsharNo ratings yet

- CH 14Document45 pagesCH 14jjupark2004No ratings yet

- A.1. Financial Statements Part 2Document53 pagesA.1. Financial Statements Part 2Kondreddi SakuNo ratings yet

- Exam 1 Section 2Document23 pagesExam 1 Section 2Chuchai Jittaviroj100% (1)

- BCO126 Mathematics of Finance: 3 Ects Spring Semester 2022Document38 pagesBCO126 Mathematics of Finance: 3 Ects Spring Semester 2022summerNo ratings yet

- 2ndQExam Finance PDFDocument1 page2ndQExam Finance PDFChristian ZebuaNo ratings yet

- 11 Accountancy SP 01Document33 pages11 Accountancy SP 01Abhay ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Prof 3 (Midterm)Document24 pagesProf 3 (Midterm)Tifanny MallariNo ratings yet

- BDO vs. Republic, 13 January 2015 and August 16, 2016Document3 pagesBDO vs. Republic, 13 January 2015 and August 16, 2016Jerry SantosNo ratings yet

Chapter Four: Project Financing

Chapter Four: Project Financing

Uploaded by

Endashew Alemu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views121 pagesProject financing involves raising long-term debt for major projects based on the cash flow from the project rather than the balance sheets of sponsors. It is commonly used for large infrastructure and resource extraction projects. Key characteristics include non-recourse or limited-recourse debt, high leverage through mostly debt financing, and lenders relying on projected cash flows from contracts/licenses rather than asset values. Project financing provides benefits to investors such as limiting liability, improving returns through leverage, obtaining tax benefits, and potentially keeping debt off balance sheets.

Original Description:

Original Title

Chapter Four

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentProject financing involves raising long-term debt for major projects based on the cash flow from the project rather than the balance sheets of sponsors. It is commonly used for large infrastructure and resource extraction projects. Key characteristics include non-recourse or limited-recourse debt, high leverage through mostly debt financing, and lenders relying on projected cash flows from contracts/licenses rather than asset values. Project financing provides benefits to investors such as limiting liability, improving returns through leverage, obtaining tax benefits, and potentially keeping debt off balance sheets.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views121 pagesChapter Four: Project Financing

Chapter Four: Project Financing

Uploaded by

Endashew AlemuProject financing involves raising long-term debt for major projects based on the cash flow from the project rather than the balance sheets of sponsors. It is commonly used for large infrastructure and resource extraction projects. Key characteristics include non-recourse or limited-recourse debt, high leverage through mostly debt financing, and lenders relying on projected cash flows from contracts/licenses rather than asset values. Project financing provides benefits to investors such as limiting liability, improving returns through leverage, obtaining tax benefits, and potentially keeping debt off balance sheets.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 121

Chapter Four: Project Financing

• The Concept of Project Finance

• A huge body of literature is available today on the subject

of structured finance in general and project in particular.

• The majority of authors agree on defining project finance

as financing that as a priority does not depend on the

soundness and credit worthiness of the sponsors, namely,

parties proposing the business idea to launch the project.

• Approval does not even depend on the value of assets

sponsors are willing to make available to financers as

collateral.

• Instead, it is basically a function of the project’s ability to

repay the debt contracted and remunerate capital

invested at a rate consistent with the degree of risk

inherent in the venture concerned.

• Project financing is an innovative and timely financing

technique that has been used on many high-profile

corporate projects.

• Employing a carefully engineered financing mix, it has long

been used to fund large-scale natural resource projects,

from pipelines and refineries to electric-generating

facilities and hydro-electric projects.

• Increasingly, project financing is emerging as the preferred

alternative to conventional methods of financing infrastructure

and other large-scale projects worldwide.

• Project financing discipline includes:

i. understanding the rationale for project financing,

ii. how to prepare the financial plan

iii. assess the risks

Iv. design the financing mix, and raise the funds.

• In addition, one must understand the cogent /well-argued

analyses of why some project financing plans have succeeded

while others have failed.

• A knowledge-base is required financing

• issues for the host government legislative provisions

• public/private infrastructure partnerships,

• public/private financing structures;

• credit requirements of lenders, and how to determine

the project's borrowing capacity;

• how to prepare cash flow projections and use them to

measure expected rates of return;

• tax and accounting considerations; and analytical

techniques to validate the project's feasibility.

• Project finance is finance for a particular project, such as a

mine, toll road, railway, pipeline, power station, ship, hospital

or prison, which is repaid from the cash-flow of that project.

• Project finance is different from traditional forms of finance

because the financier principally looks to the assets and

revenue of the project in order to secure and service the

loan.

• In contrast to an ordinary borrowing situation, in a project

financing the financier usually has little or no recourse to the

non-project assets of the borrower or the sponsors of the

project.

• In this situation, the credit risk associated with

the borrower is not as important as in an

ordinary loan transaction;

• what is most important is the identification,

analysis, allocation and management of every

risk associated with the project.

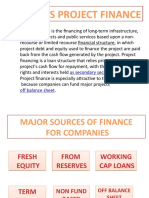

• Project finance is a method of raising long-term

debt financing for major projects through

“financial engineering,” based on lending against

the cash flow generated by the project alone;

• it depends on a detailed evaluation of a project’s

construction, operating and revenue risks, and

their allocation between investors, lenders, and

other parties through contractual and other

arrangements.

• It is a technique that has been used to raise huge amounts of

capital and promises to continue to do so, in both developed

and developing countries, for the foreseeable future.

• Project finance is generally used to refer to a non-recourse

or limited recourse financing structure in which debt, equity

and credit enhancement are combined for the construction

and operation,

• or the refinancing, of a particular facility in a capital-

intensive industry.

• Project finance is a relatively new financial discipline that has

developed rapidly over the last 20 years.

Development of Project Finance

• The growth of project finance over the last 20

years has been driven mainly by the worldwide

process of deregulation of utilities and

privatization of public-sector capital investment.

• This has taken place both in the developed

world as well as developing countries.

• It has also been promoted by the

internationalization of investment in major

projects:

• leading project developers now run worldwide

portfolios and are able to apply the lessons

learned from one country to projects in

another, as are their banks and financial

advisers.

• Governments and the public sector generally

also benefit from these exchanges of

experience.

Features of project finance

• Project finance structures differ between

these various industry sectors and from deal

to deal:

• there is no such thing as “standard” project

finance, since each deal has its own unique

characteristics.

• But there are common principles underlying

the project finance approach.

Some typical characteristics of project

finance are:

a. It is provided for a “ring fenced” project (i.e., one which

is legally and economically self-contained) through a

special purpose legal entity (usually a company) whose

only business is the project (the “Project Company”).

b. It is usually raised for a new project rather than an

established business (although project finance loans

may be refinanced).

c. There is a high ratio of debt to equity (“leverage” or

“gearing”)—roughly speaking, project finance debt may

cover 70 –90% of the cost of a project.

d. There are no guarantees from the investors in the Project

Company (“nonrecourse” finance), or only limited guarantees

(“limited-recourse” finance), for the project finance debt.

e. Lenders rely on the future cash flow projected to be generated

by the project for interest and debt repayment (debt service),

rather than the value of its assets or analysis of historical

financial results.

f. The main security for lenders is the project company’s contracts,

licenses, or ownership of rights to natural resources; the project

company’s physical assets are likely to be worth much less than

the debt if they are sold off after a default on the financing.

g. The project has a finite life, based on such

factors as the length of the contracts or

licenses or the reserves of natural resources,

and therefore the project finance debt must

be fully repaid by the end of this life.

• Hence, project finance differs from a

corporate loan, which is primarily lent against

a company’s balance sheet and projections

extrapolating from its past cash flow and profit

record, and assumes that the company will

remain in business for an indefinite period and

so can keep renewing (“rolling over”) its loans.

• Project finance is made up of a number of

building blocks, although all of these are not

found in every project finance transaction, and

there are likely to be ancillary contracts or

agreements.

• The project finance itself has two elements:

1. Equity, provided by investors in the project

2. Project finance-based debt, provided by one or

more groups of lenders

Principal Advantages and Disadvantages of

Project Financing

• Benefits of Project Finance to Investors

• Investors use project finance for the following variety of

reasons:

A. Non-Recourse

• The typical project financing involves a loan to enable the

sponsor to construct a project where the loan is completely

"non-recourse" to the sponsor, i.e., the sponsor has no

obligation to make payments on the project loan if

revenues generated by the project are insufficient to cover

the principal and interest payments on the loan.

• In order to minimize the risks associated with

a non-recourse loan, a lender typically will

require indirect credit supports in the form of

guarantees, warranties and other

covenants/agreements from the sponsor, its

affiliates and other third parties involved with

the project.

b. High Leverage

• One major reason for using project finance is

that investments in ventures such as power

generation or road building have to be long

term but do not offer an inherently high

return: high leverage improves the return for

an investor.

• Project finance thus takes advantage of the fact

that debt is cheaper than equity, because

lenders are willing to accept a lower return (for

their lower risk) than an equity investor.

• Naturally the investor needs to be sure that the

investment in the project is not jeopardized by

loading it with debt, and therefore has to go

through a sound due diligence process to

ensure that the financial structure is prudent.

• Of course the argument could be turned the

other way around to say that if a project has

high leverage it has an inherently higher risk,

and so it should produce a higher return for

investors.

• But in project finance higher leverage can only

be achieved where the level of risk in the

project is limited.

c. Tax Benefits

• A further factor that may make high leverage more

attractive is that interest is tax deductible, whereas

dividends to shareholders are not, which makes debt even

cheaper than equity, and hence encourages high leverage.

• In major projects there is, however, likely to be a high

level of tax deductions anyway during the early stages of

the project because the capital cost is depreciated against

tax, so the ability to make a further deduction of interest

against tax at the same time may not be significant.

d. Off-balance-sheet financing

• If the investor has to raise the debt and then

inject it into the project, this will clearly appear

on the investor’s balance sheet.

• A project finance structure may allow the

investor to keep the debt off the consolidated

balance sheet, but usually only if the investor

is a minority shareholder in the project—which

may be achieved if the project is owned

through a joint venture.

• Keeping debt off the balance sheet is sometimes seen as

beneficial to a company’s position in the financial markets,

• but a company’s shareholders and lenders should normally

take account of risks involved in any off-balance-sheet

activities, which are generally revealed in notes to the

published accounts even if they are not included in the

balance sheet figures;

• so although joint ventures often raise project finance for

other reasons (discussed below), project finance should

not usually be undertaken purely to keep debt off the

investors’ balance sheets.

e. Borrowing Capacity

• Project finance increases the level of debt that

can be borrowed against a project: nonrecourse

finance raised by the Project Company is not

normally counted against corporate credit lines

(therefore in this sense it may be off-balance

sheet).

• It may thus increase an investor’s overall

borrowing capacity, and hence the ability to

undertake several major projects simultaneously.

f. Risk Limitation

• An investor in a project raising funds through

project finance does not normally guarantee

the repayment of the debt—the risk is

therefore limited to the amount of the equity

investment.

• A company’s credit rating is also less likely to

be downgraded if its risks on project

investments are limited through a project

finance structure.

g. Risk Spreading / Joint Ventures

• A project may be too large for one investor to

undertake, so others may be brought in to

share the risk in a joint-venture Project

Company.

• This both enables the risk to be spread

between investors and limits the amount of

each investor’s risk because of the

nonrecourse nature of the Project Company’s

debt financing.

• As project development can involve major

expenditure, with a significant risk of having to

write it all off if the project does not go ahead

(cf. §4.2),

• a project developer may also bring in a

partner in the development phase of the

project to share this risk.

• This approach can also be used to bring in

“limited partners” to the project (e.g., by

giving a share in the equity of a Project

Company to an Off taker who is thus induced

to sign a long-term Off take Contract, without

being required to make any cash investment,

or with the investment limited to a small

proportion of the equity.)

• Creating a joint venture also enables project

risks to be reduced by combining expertise

(e.g., local expertise plus technical expertise;

construction expertise plus operating expertise;

operating expertise plus marketing expertise).

• In such cases the relevant Project Contracts

(e.g., the EPC Contract or the O&M Contract)

are usually allocated to the partner with the

relevant expertise.

h. Long-Term Finance

• Project finance loans typically have a longer term

than corporate finance.

• Long-term financing is necessary if the assets

financed normally have a high capital cost that

cannot be recovered over a short term without

pushing up the cost that must be charged for the

project’s end product.

• So loans for power projects often run for nearly 20

years, and for infrastructure projects even longer.

• (Oil, gas, and minerals projects usually have a

shorter term because the reserves extracted

deplete more quickly and

• telecommunication projects also have a

shorter term because the technology involved

has a relatively short life.)

i. Enhanced Credit

• If the Off taker has a better credit standing

than the equity investor, this may enable debt

to be raised for the project on better terms

than the investor would be able to obtain

from a corporate loan.

j. Unequal Partnerships

• Projects are often put together by a developer

with an idea but little money, who then has to

find investors.

• A project finance structure, which requires less

equity, makes it easier for the weaker

developer to maintain an equal partnership,

because if the absolute level of the equity in

the project is low, the required investment

from the weaker partner is also low.

The Benefits of Project Finance to Third

Parties

• Equally, there are benefits for the off taker or end

user of the product or service provided by the

Project Company, and also for the government of the

country where the project is located:

a. Lower Product or Service Cost

• In order to pay the lowest price for the project’s

product or service, the Off taker or end user will

want the project to raise as high a level of debt as

possible, and so a project finance structure is

beneficial.

• This can be illustrated by doing the calculation in Table 2.2

in reverse:

• suppose the investor in the project requires a return of at

least 15%, then, as Table 2.3 shows, to produce this,

revenue of 120 is required using low leverage finance, but

only 86 using high leverage project finance, and hence the

cost to the Off taker or end user reduces accordingly.

• (In finance theory, an equity investor in a company with

high leverage would expect a higher return than one in a

company with low leverage, on the ground that high

leverage equals high risk).

• However, as discussed above, this effect cannot be

seen in project finance investment, since its high

leverage does not imply high risk.)

• (Also cf. §13.1 for other issues affecting leverage.)

• So if the Off taker or end user wishes to fix the lowest

long-term purchase cost for the product of the project

and is able to influence how the project is financed,

• the use of project finance should be encouraged, e.g.,

by agreeing to sign a Project Agreement that fits

project finance requirements.

b. Additional Investment in Public

Infrastructure

• Project finance can provide funding for

additional investment in infrastructure that

the public sector might otherwise not be able

to undertake because of economic or financial

constraints on the public-sector investment

budget.

• Of course, if the public sector pays for the project

through a long-term Project Agreement,

• it could be said that a project financed in this way

is merely off-balance sheet financing for the

public-sector, and should therefore be included in

the public-sector budget anyway.

• Whether this argument is a valid one depends on

the extent to which the public sector has

transformed real project risk to the private sector.

c. Risk Transfer

• A project finance contract structure transfers

risks of, for example, project cost overruns

from the public to the private sector.

• It also usually provides for payments only

when specific performance objectives are

met, hence also transferring to the private

sector the risk that these are not met.

c. Lower Project Cost

• Private finance is now widely used for projects that

would previously have been built and operated by

the public sector.

• Apart from relieving public sector budget pressures,

such PPP projects also have merit because the

private sector can often build and run such

investments more cost-effectively than the public

sector, even after allowing for the higher cost of

project finance compared to public-sector finance.

• This lower cost is a function of:

• The general tendency of the public sector to

“overengineer” or “gold plate” projects

• Greater private-sector expertise in control and

management of project construction and

operation (based on the private sector being

better able to offer incentives to good managers)

• The private sector taking the primary risk of

construction and operation cost overruns, for

which public-sector projects are notorious

• “Whole life” management of long-term

maintenance of the project, rather than ad hoc

/public notice arrangements for maintenance

dependent on the availability of further public-

sector funding.

• However, this cost benefit can be eroded by “deal

creep” (i.e., increases in costs during detailed

negotiations on terms or when the specifications

for the project are changed during this period.

d. Third-Party Due Diligence

• The public sector may benefit from the

independent due diligence and control of the

project exercised by the lenders, who will

want to ensure that all obligations under the

Project Agreement are clearly fulfilled and

that other Project Contracts adequately deal

with risk issues.

f. Transparency

• As a project financing is self-contained (i.e., it deals

only with the assets and liabilities, costs, and

revenues of the particular project), the true costs

of the product or service can more easily be

measured and monitored.

• Also, if the Sponsor is in a regulated business (e.g.,

power distribution, the unregulated business can

be shown to be financed separately and on an

arm’s-length basis via a project finance structure.

g. Additional Inward Investment

• For a developing country, project finance

opens up new opportunities for infrastructure

investment, as it can be used to create inward

investment that would not otherwise occur.

• Furthermore, successful project finance for a

major project, such as a power station, can act

as a showcase /platform to promote further

investment in the wider economy.

g. Technology Transfer

• For developing countries, project finance

provides a way of producing market-based

investment in infrastructure for which the

local economy may have neither the resources

nor the skills.

Disadvantages of Project Finance

a. Complexity of risk allocation

• Project financings are complex transactions

involving many participants with diverse

interests.

• This results in conflicts of interest on risk

allocation amongst the participants and

protracted negotiations and increased costs to

compensate third parties for accepting risks.

b. Increased Lender Risk

• Since banks are not equity risk takers, the

means available to enhance the credit risk to

acceptable levels are limited, which results in

higher prices.

• This also necessitates expensive processes of

due diligence conducted by lawyers, engineers

and other specialized consultants.

c. Higher Interest Rates and Fees

• Interest rates on project financings may be

higher than on direct loans made to the

project sponsor since the transaction structure

is complex and the loan documentation

lengthy.

• Project finance is generally more expensive

than classic lending because of:

• The time spent by lenders, technical experts and

lawyers to evaluate the project and draft complex loan

documentation;

• The increased insurance cover, particularly political

risk cover;

• The costs of hiring technical experts to monitor the

progress of the project and compliance with loan

covenant;

• The charges made by the lenders and other parties for

assuming additional risks.

d. Lender Supervision

• In order to protect themselves, lenders will want to closely

supervise the management and operations of the project (whilst

at the same time avoiding any liability associated with excessive

interference in the project).

• This supervision includes site visits by lender’s engineers and

consultants, construction reviews, and monitoring construction

progress and technical performance, as well as financial

covenants to ensure funds are not diverted from the project.

• This lender supervision is to ensure that the project proceeds as

planned, since the main value of the project is cash flow via

successful operation.

e. Lender Reporting Requirements

• Lenders will require that the project company

provides a steady stream of financial and technical

information to enable them to monitor the

project’s progress.

• Such reporting includes financial statements,

interim statements, reports on technical progress,

delays and the corrective measures adopted, and

various notices such as events of default.

f. Increased Insurance Coverage

• The non-recourse nature of project finance

means that risks need to be mitigated.

• Some of this risk can be mitigated via insurance

available at commercially acceptable rates.

• This however can greatly increase costs, which

in itself, raises other risk issues such as pricing

and successful syndication.

g. Transaction Costs May Outweigh the Benefits

• The complexity of the project financing arrangement

can result in a transaction whose costs are so great

as to offset the advantages of the project financing

structure.

• The time-consuming nature of negotiations amongst

various parties and government bodies, restrictive

covenants, and limited control of project assets, and

burgeoning legal costs may all work together to

render the transaction unfeasible.

Common Misconceptions about Project

Finance

• There are several misconceptions about project

finance:

• The assumption that lenders should in all

circumstances look to the project as the exclusive

source of debt service and repayment is

excessively rigid and can create difficulties when

negotiating between the projects participants.

• Lenders do not require a high level of equity

from the project sponsors.

• The assets of the project provide 100% security.

• The project’s technical and economic

performance will be measured according to pre-

set tests and targets.

• Lenders will not want to abandon the project as

long as some surplus cash flow is being generated

over operating costs, even if this level represents

an uneconomic return to the project sponsors.

• Lenders will often seek assurances from the

host government about the risks of

expropriation and availability of foreign

exchange.

• Often these risks are covered by insurance or

export credit guarantee support.

CHAPTER FIVE: PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION

• 5.1 The Concept and Purpose of Project Implementation

• This is the crucial stage of any project since the objective of

the earlier effort in the stages above was to have projects to

be undertaken.

• The implementation period usually has three phases: the

investment period, the development period, and full

development.

• This forms the life of the project.

• The investment period refers to when the major project

investments are undertaken and could take one to three

years, depending on the nature of the project.

5.2 Problems in Project Implementation

• There are enormous problems in project implementation.

• Particularly in developing countries like ours, the nature

and degree of problems varies from sector to sector, from

project to project, from region to region, and from area to

area.

• However, for the convenience of discussion, the

commonly encountered project implementation problems

are divided in to four categories.

• These are financial, managerial and institutional, technical

and political.

1. Financial Problems:

• Financial difficulties occur frequently during project

implementation.

• Inadequate allocation of budgetary funds,

• shortage of foreign exchanges ( for projects constitute

foreign components),

• delay in budget releases,

• general price and salary increases,

• change in tariff and interest rates, and

• losses due to fluctuations in foreign exchange rates are

the most common causes of financial problems:

The effects of financial difficulties on

implementation are:

• Delay /interruption of project activities

• Cost increase ( over - run)

• Reduction in the scope of the project

• In our country what is usually observed is a mismatch

between the investment programs prepared and the

financial resources available to implement them.

• When this happens, the flow of funds for project

finance will frequently interrupted and project activities

are postponed from one budgetary year to the

subsequent one.

• In some cases even when funds are available

there is a chronic delay by responsible

government agencies in paying their bills for

various reasons.

• This again results with implementation delays.

• A vicious circle is then started.

2. Management Problems:

• This encompasses what are usually considered institutional

problems.

• Managerial problems can be manifested:

a. In the top government administration,

b. In the regional or local levels, and

c. In the upper or middle management of the project and/or

implementing agencies.

• An ill defined organizational set -up, low salaries and poor

staffing policies:

• lack of coordination among various agencies that influence the

project implementation, and

• discontinuity of management as a result of changes for

political and other reasons, etc, are some features of

management problems.

• Weak management and institutional capacity is a reflection of

lack of skilled manpower,

• inadequate monitoring and evaluation system,

• inadequate project coordination and lack of information

system.

• These managerial and institutional problems are often the

root cause of implementation delays and cost over - runs.

3. Technical Problems:

• In many cases technical problems result from the poor

estimates and projections on the project activities and

characters during the preparation stage.

• For example, in engineering area such problems as difficult

soil conditions, poor quality of materials, technical defects

in design, mistakes in installation and start- up of

equipment, unsuitability of imported equipment for local

conditions, etc,

• And in agriculture, inadequate technical packages,

inadequate awareness of the beneficiary farmers, etc are

some of the frequently observed problems.

4. Political Problems:

• When government (at all levels) commitment is

absent, weak or changing, obviously project

implementation suffers.

• A rapid rotation of political appointees in some areas

considerably influences success in project

implementation.

• Project management has to take in to account the

potential impact of such political and administrative

factors, anticipate the problems in so far as possible,

and modify the implementation path accordingly.

5. Other Problems:

• Donor conditionality,

• lengthy project approval and fund

disbursement procedures of donors (financing

agencies),

• low community involvements in project

planning and implementation, etc., are the

other contributing factors in delay of

implementation.

5.3 Pre-Requisites for Successful Project

Implementation

• A successful project implementation means

that the project has been completed on time,

at or reasonably close to the original cost

estimates, and with the expected benefits

realized or even exceeded.

• The following are some of the principal factors

that could account for successful projects and

then those that lead to problems and

difficulties during implementation.

1. Adequate Formulation

• Often project formulation is deficient because of one or more of

the following shortcomings. These include:

• Superficial field investigation;

• hasty assessment of input requirements;

• careless methods used for estimating costs and benefits;

• omission of project linkages;

• flawed judgments because of lack of experience and expertise;

• undue hurry to get started;

• deliberate over-estimation of benefits and under-estimation of cost

• Care must be taken to avoid the above deficiencies so that the

appraisal and formulation of the project is thorough, adequate,

and meaningful.

2. Political Commitment:

• Strong and sustained commitment by all levels of the

government body (national, regional, zonal, wereda,

and kebele) to the project's objectives is the first and

probably most important reason for success.

• Political or government commitment-through

allocation of human, financial and other resources or

administrative and political apparatus.

• It is strongly advisable that stakeholders' participation

and consultation during project preparation would

help to ensure commitments

3. Simplicity of Design:

• Selection of proper project design is central to successful

project implementation.

• Projects with relatively simple and well - defined objectives

and based on proven and appropriate technologies or

approaches have a better chance of being implemented

successfully.

• The major success factors in some rural development

programs and projects appear to have been the

appropriateness of the technologies proposed for the

specific local conditions, the complement of recommended

inputs, and the strength of the support systems, etc.

4. Careful Preparation:

• Project must be sufficiently prepared before it started.

• Careful preparation includes not only matters such as detailed

engineering and land acquisition but also other technological

packages, socio - economic factors, environmental issues,

organizational and institutional arrangements, and other

supporting services.

• For a big project, like that of rural development, pilot project is

sometimes important to test proposed activities and approaches

under local conditions.

• This would not only improve success in implementation but also

help to save both time and money that might be unnecessarily

spent.

5. Good Management:

• The influence of the quality of management on project

implementation performance is usually visible.

• Many projects in serious difficulty during implementation

have been turned around by the appointment of a competent

manager.

• What are the qualities of good manager and management?

• Superior performance in managerial job is associated with

performing satisfactorily key areas' of the job.

• A key area can be defined as a major component of a

managerial job of such importance that its failure to perform

satisfactorily will endanger the whole job.

6. Advance Action:

• When the project appears prima face to viable and desirable,

advance action on the following activities may be initiated:

a. acquisition of land,

b. securing essential clearances,

c. identifying technical collaborators/consultants,

d. arranging for infrastructure facilities,

e. preliminary design and engineering, and

f. Calling of tenders.

• To initiate advance action with respect to the above activities,

some investment is required.

• Clearly, if the project is not finally approved,

this investment would represent an

anfractuous outlay.

• However, the substantial saving (in time and

cost) that are expected to occur, should the

project be approved (a very likely event, given

the prima facie desirability of the project)

often amply the incurrence of such costs

7. Timely Availability of Funds:

• Once a project is approved, adequate funds

must be made available to meet its

requirements as per the plan of

implementation-

• it would be highly desirable if funds are

provided even before the final approval to

initiate advance action.

8. Judicious Equipment Tendering and

Procurement.

• To minimize time over-runs, it may appear that

a turnkey contract has obvious advantages.

• Since these contracts are likely to be bagged by

foreign suppliers, when global tenders are

floated, a very important question arises.

• How much should we rely on foreign suppliers

and how much should we depend on

indigenous suppliers?

• Over- dependence on foreign suppliers, even though

seemingly advantageous from the point of view of time and

cost, may mean considerable outflow of foreign exchange

and inadequate incentive for the development of

indigenous technology and capability.

• Over-reliance on indigenous suppliers may mean delays and

higher uncertainty about the technical performance of the

project.

• A judicious balance must be sought which moderates the

outflow of foreign exchange and provides reasonable

stimulus to the development of indigenous technology.

• In any case, the number of contract packages should be kept

to a minimum in order to ensure effective coordination.

9. Better Contract Management:

• In this context, the following should be done:

• The competence and capability of all the contractors must be ensured-

one weak link can jeopardize the timely performance of the contract

• Proper discipline must be inculcated among contractors and suppliers by

insisting that they should develop realistic and detailed resources and

time plans which are congruent with the project plan.

• Penalties-which may be graduated- must be imposed for failure to meet

contractual obligations. Likewise, incentives may be offered for good

performance.

• Help should be extended to contractors and suppliers when they have

genuine problems-they should be regarded as partners in a common

pursuit.

• Project authorities must retain latitude to off-load contracts (partially or

wholly) to other parties well in time where delays are anticipated.

10. Effective Monitoring:

• In order to keep a tab on the progress of the

project, a system of monitoring must be

established. This helps in:

• Anticipating deviations from the

implementation plan.

• Analyzing emerging problems.

• Taking corrective action.

• In developing a system of monitoring, the following

points must be borne in mind:

– It should focus sharply on the critical aspects of project

implementation.

– It must lay more emphasis on physical milestones and not

on financial targets.

– It must be kept relatively simple. If made over-

complicated, it may lead to redundant paper work and

diversion of resources. Even worse, monitoring may be

viewed as an end in itself rather than as a means to

implement the project successfully.

11. Other Factors:

• In addition to the above list, the followings are the

other contributing factors for project

implementation success:

• Well defined goals and objectives,

• Agreement over goals and objectives among the

participants in the project

• Detailed work break - down structure and

commitment to achieving goals and objectives, and

• Reliable monitoring and tracking techniques, etc.

CHAPTER SIX: PROJECT MONITORING &

EVALUATION

• 6.1The Concept of Monitoring and Evaluation

• Monitoring can be defined as a continuous assessment of

both the functioning of the project activities in the context

of implementation schedules and the use of project inputs

by targeted populations in the context of designed

expectations.

• This should be an on-going activity during implementation.

• Monitoring can be carried out by the beneficiaries, the

managing staff, supervisory staff and the project

management staff.

• The aim should be to ensure that the activities of the project are

being undertaken on schedule to facilitate implementation as

specified in the project design.

• Any constraints in implementing the design can quickly be

detected and corrective action taken.

• Key questions in project monitoring include:

– Are the right inputs being supplied/delivered at the right time?

– Are the planned inputs producing the planned outputs?

– Are the outputs leading to the achievement of the planned objectives?

– Is the policy environment consistent with the design assumptions?

– Are the project objectives still valid?

• Monitoring is an internal project activity, an essential

part of good management practice, and, therefore, an

integral part of the day-to-day management.

• The term has a close meaning with control and

supervision.

• Evaluation, on the other hand, can be defined as a

periodic assessment of the relevance, efficiency,

effectiveness, impact, economic and financial viability,

and sustainability of a project in the context of its

stated objectives.

• The purpose of evaluation is to review the achievements

of a project against planned expectations, and to use

experience from the project to improve the design of

future projects and programs.

• Evaluation draws on routine reports produced during

implementation and may include additional investigations

by external monitors or by specially constituted missions.

• This implies that evaluation is a continuous exercise

during the project life and is much related to project

monitoring.

• Monitoring provides the data on which the evaluation is

based. However, formalized evaluation is undertaken at

specified periods.

• There is usually a mid-term and a terminal evaluation.

• Evaluation can also be undertaken when the project is in

trouble as the first step in a re-planning effort.

• Careful evaluation is also undertaken before any follow-up

project.

• Evaluation can be done internally or by external reviewers.

Some organizations have monitoring and evaluation units.

• Such a unit can provide project management with useful

information to ensure efficient implementation of projects,

• especially if it operates independently and objectively,

• because what the unit needs is to judge projects on the basis

of objectives, original project design and the reality on the

ground (the operating physical and policy environment).

• With no free hand, the feedback mechanism will be stifled

and information be “held-back” instead of being “fed-back”.

• The aim of evaluation is largely to determine the extent to

which the objectives are being realized.

• Evaluation, an essential ingredient of project management, is

concerned with the following critical questions:

• Are or have objectives being/been met? If not, were the objectives

realistic?

• Was the technology proposed appropriate?

• Was the institutional, management arrangements suited to the

conditions?

• Were the financial aspects carefully worked out?

• Were the economic aspects carefully explored?

• Did management quickly respond to changes?

• Was its response carefully considered and appropriate?

• How could the project’s structure be changed to make it more flexible?

6.2 Common Problems with Monitoring and

Evaluation

• There are several limiting factors for successful

monitoring and evaluation of development

projects.

• In the Ethiopian case, the following are the

most important frequently mentioned

problems:

• Insufficient awareness of the purpose of monitoring and evaluation

and inadequate attention paid to project implementation.

• Monitoring and evaluation activities are not seen as distinct

responsibility in their own and not given proper consideration.

• People rather feel monitoring and evaluation as faultfinding mission

and limit their cooperation for the activity.

• Inadequate or lack of monitoring and evaluation unit and staff both

at the project level and higher implementing body.

• In most cases, monitoring and evaluation system is not either

properly established or not provided with adequate attention and

resources where it exists.

• Poor accountability for failures and inadequate reward for special

efforts made towards successful project implementation.

• Limited training opportunity for monitoring and evaluation personnel

in projects or offices where the unit exists.

• Limited information source on project progress.

• Even information is available; it doesn’t answer the right questions.

• Frequently where the system exists it focus only on quantitative

financial aspects and physical implementation of the program/project.

• Late arrival of information required for monitoring.

• Too costly to collect information.

• Disregard of previous monitoring and evaluation findings in the design

of new projects.

• High mobility of project staff disrupting continuity of monitoring and

evaluation functions.

CHAPTER 7: PROJECT PROPOSAL WRITING

• Overview

• A project proposal is a detailed description of a series of activities

aimed at solving a certain problem.

• A technical proposal, often called a "Statement of Work,” is a persuasive

document.

• Its objectives are to:

• Identify what work is to be done

• Explain why this work needs to be done

• Persuade the reader that the proposers (you) are qualified for the work,

• have a plausible management plan and technical approach, and have

the resources needed to complete the task within the stated time and

cost constraints.

• The project proposal should be a detailed and

directed manifestation of the project design.

• It is a means of presenting the project to the

outside world in a format that is immediately

recognized and accepted.

• There are critical issues that must be examined in

advance of the actual preparation of project

proposal.

• These include:

• Interview past and prospective beneficiaries

• Though feedback was likely received when the previous project

ended, new benefits and conditions may have arisen since that

time.

• Speak to prospective beneficiaries to ensure that what you are

planning to offer is desired and needed.

• Review past project proposals.

• Avoid repeating mistakes and offering to reproduce results that have

already been achieved.

• Donors will be unlikely to provide more funding for something that

should already have been done.

• Review past project evaluation reports

• Organize focus groups

• Make sure that the people you need are willing and able to

contribute.

• Check statistical data

• Don’t let others discover gaps and inaccuracies in the data you are

relying on.

• Consult experts

• Outside opinions will give you ideas and credibility.

• Conduct surveys, etc. Gather as much preliminary information as

possible to demonstrate commitment to the project and to refine

the objectives.

• Hold community meetings or forums

How to Write a Project Proposal

• Once the groundwork has been completed,

proposal writing can begin.

• The key decision to be made at this stage is

the structure of the project proposal

(including the content and length).

• The structure is determined by the nature of

the project as well as by the funding agency’s

requirements.

• Project Proposal Format

• There is no single fixed and universally accepted structure

for the development of a project proposal.

• General guideline within which one can make an adjustment

depending on the overall context of the problem under

consideration and situational factors that directly or

indirectly can affect implementation of the project.

• Accordingly, an ideal project must involve the following

elements.

• These include:

1. Title Page

• A title page should appear on proposals longer than three to four

pages.

• The title page should indicate:

• The project title in initial capital letters

• The name of the lead organization (and potential partners, if any),

• Team name and individual member names

• Date

• An appropriate picture of the product, a team logo, or both

• The project title should be short, concise, and preferably refer to a

certain key project result or the leading project activity.

• Project titles that are too long or too general fail to give the reader

an effective snapshot of what is inside.

Contents Page

• If the total project proposal is longer than 10

pages it is helpful to include a table of

contents at the start or end of the document.

• The contents page enables readers to quickly

find relevant parts of the document.

• It should contain the title and beginning page

number of each section of the proposal.

Abstract/ Executive Summary

• Abstract which sometimes is also called Executive Summary is a brief

summary of the proposal.

• Many readers lack the time needed to read the whole project proposal.

• It is therefore useful to insert a short project summary-an abstract.

• For this reason, an Abstract/ Executive Summary should summarize the

proposal so that a reviewer knows what to expect when reading the rest of

it.

• It also should be helpful for any others who may not be reviewers, but

need to understand and approve the general concept of the proposed

research.

• This summary should not include information not explained in greater

detail later in the proposal.

• The abstract should include:

• The problem statement;

• The project’s objectives;

• Implementing organizations;

• Key project activities; and

• The total project budget.

• For a small project the abstract may not be longer

than 10 lines.

• Bigger projects often provide abstracts as long as

two pages.

Project Background/Context

• This part of the project describes the social, economic,

political and cultural background from which the project is

initiated.

• It should contain relevant data from research carried out in

the project planning phase or collected from other sources.

• The writer should take into consideration the need for a

balance between the length of this item and the size of the

overall project proposal.

• Large amounts of relevant data should be placed in an

annex.

Project Rationale/Project Justification

• At this stage it is important to clarify why this

particular project is needed, as opposed to all

the other possible projects that might be

proposed to address the same problem.

• Due to its importance usually this section is

divided into four or more sub-sections.

• These include:

5.1. Problem Statement

• The problem statement provides a description of the

specific problem(s) the project is trying to solve, in

order to “make a case” for the project.

• Furthermore, the project proposal should point out

why a certain issue is a problem for the community

or society as a whole, i.e. what negative implications

affect the target group.

• There should also be an explanation of the needs of

the target group that appear as a direct consequence

of the described problem.

– Priority Needs

• The needs of the target group that have arisen as a

direct negative impact of the problem should be

prioritized.

• An explanation as to how this decision was reached

(i.e. what criterion was used) must also be included.

-The Proposed Approach (Type of Intervention)

• The project proposal should describe the strategy

chosen for solving the problem and precisely how it

will lead to improvement.

– The Implementing Organization

• This section should describe the capabilities of your

organization by referring to its capacity and previous project

record.

• Describe why exactly your organization is the most

appropriate to run the project

• its connection to the local community,

• the constituency behind the organization and what kind of

expertise the organization can provide.

• If other partners are involved in implementation provide

some information on their capacity as well.

• Project Goal and Objectives

• 6.1 Project Goal/Overall Objective/Aim

• This is a general aim that should explain what the core

problem is and why the project is important, i.e. what the

long-term benefits to the target group are.

• In principle, there should be only one goal per project. The

goal should be connected to the vision for development.

• It is difficult or impossible to measure the accomplishment

of the goal using measurable indicators, but it should be

possible to prove its merit and contribution to the vision.

• 6.2 Project Objectives/Project Purpose/Project Immediate

Objectives

• This is a more refined, specific, measurable, achievable, real,

and time bounded activities that contribute to the overall

achievement of a project goal.

• Project Implementation and Management Plan

• It is a kind of framework within which the project’s specific

objectives and the necessary project activities are stated in a

clear, precise, and meaningful manner along with the

responsible bodies/organizations.

• Project Activities: Format

• Work Plan /Activity Plan

• The activity plan should include specific information and

explanations of each of the planned project activities.

• The duration of the project should be clearly stated, with

considerable detail on the beginning and the end of the

project.

• In general, two main formats are used to express the activity

plan: a simple table and the Gantt chart.

• A simple table with columns, sub-activities, tasks, timing and

responsibility, is a clear, readily understandable format for

the activity plan.

• Project Implementation Management Strategy

• 8.1 Implementation Strategies

• Implementation strategies refer to the basic mechanisms the project

manager devises to actually carry out the project. These include:

• Distribution of leaflets,

• preparation of symposiums and trainings,

• Meetings with community groups and conducting focus group discussions,

etc.

• Implementation strategies of projects can vary from one to other

depending on the nature and characteristics of the discipline;

• the methodological approach of project planners;

• the actual context of the problem under consideration, and many other

possible reasons.

• 8.2 Sustainability

• Sustainability of a project implies the future fate of the project mainly

after the intervention/implementation period is completed.

• In this section of the proposal, the project manager should outline the key

mechanisms that can likely sustain the impact of the project done on a

certain problem and in certain community.

• Some factors can affect sustainability of projects. These include:

• Organizational sustainability

• Is the division of responsibilities between various organizations, groups

and or individuals clear?

• Have various stakeholders participated in planning, decision making and

implementation?

• Is the management plan good?

• Finance

• Have the long-term running costs been considered?

• Are there other possibilities for long-term financing?

• Technology

• Are local technologies and equipment being used?

• Does the project build on existing local expertise?

• Is there any training required?

• Risks

• Are there organizations or individuals who would prefer that the project

not be successful, and if so have any steps been taken to offset the

threat?

• Is there legislation that could negatively affect the success of the

project?

• In your proposal, you have to describe what steps you are taking to make

sure your project will be sustainable.

• Furthermore, you should effectively illustrate your long term plans for

continuing the work beyond the life of the project.

• Besides, the way will you use the results and resources developed by

this project and other resources can you create must be stated in a clear

and comprehensive manner.

• Risks and Assumptions

• At this part of the project proposal, the project

manager together with the project team

members should wisely predict and illustrate the

possible risk/s of the project,

• its probability, degree of impact, and possible

mitigation strategies.

• Risks and assumptions of a project are usually

stated in the following format.

• Expected Project Results

• This section of the project proposal states the possible results of the project.

• It is usually stated in the form of the following format.

• Monitoring and Evaluation

• At this stage of the project proposal the project manager/ project owners

should clearly indicate the ways of monitoring and evaluating the overall

project implementation process.

• More specifically, the project proposal should indicate:

• How and when the project management team will conduct activities to

monitor the

• Project’s progress;

• Which methods will be used to monitor and evaluate; and

• Who will do the evaluation

• Reporting

• The schedule of project progress and financial report could be set in the project

proposal.

• Often these obligations are determined by the standard requirements of the donor

agency.

• The project report may be compiled in different versions, with regard to the audience

they are targeting.

• Management and Personnel

• A brief description should be given of the project personnel, the individual roles each

one has assumed, and the communication mechanisms that exist between them.

• Budget

• In simple terms, a budget is an itemized summary of an organization’s expected

income and expenses over a specified period of time.

• The two main elements of any budget are income and expenditures.

• References

• References refer to anything cited in the text of the proposal.

• One must acknowledge the author/s of the source material/s used in

the development of the project proposal.

• A separate section entitled "Bibliography" lists other materials (books,

journal articles, etc.)

• related to the project but not specifically referred to in the document.

• Annexes

• The annexes should include all the information that is important, but is

too large to be included in the text of the proposal.

• This information can be created in the identification or planning phase

of the project, but often it is produced separately.

• The usual documentation to be annexed to the project proposal is:

• Analysis related to the general context

• Policy documents and strategic papers

• Information on the implementing organizations (e.g. annual

reports, success stories, brochures and other publications)

• Additional information on the project management

structure and personnel (curriculum vital for the members

of the project team);

• Maps of the location of the target area; and

• Project management procedures and forms (organizational

charts, forms, etc).

• QUALITIES OF A WELL WRITTEN PROJECT PROPOSAL

• A well written project proposal should be:

• Clear: which implies that the proposal should convey one and only one

meaning to what is written and it can be easily understood by the

reader.

• Accurate and Objective: which is to mean that facts must be written as

exactly as they are and presented fully and fairly;

• Accessible: project proposal must be developed in a way which is easy to

find needed information;

• Concise: conciseness of a project proposal implies that the proposal

must be written in a brief, direct, and in a to the point manner.

• Correct: the project proposal must be correct in grammar, punctuation,

and usage.

You might also like

- FR - MID - TERM - TEST - 2020 CPA Financial ReportingDocument13 pagesFR - MID - TERM - TEST - 2020 CPA Financial ReportingH M Yasir MuyidNo ratings yet

- FOF Tutorial 9 AnsDocument6 pagesFOF Tutorial 9 AnsYasmin Zainuddin100% (1)

- Pizza Hut Corporation Has Decided To Enter The Catering BusinessDocument2 pagesPizza Hut Corporation Has Decided To Enter The Catering Businesstrilocksp Singh0% (1)

- Credtrans Activity CasesDocument5 pagesCredtrans Activity CasesChaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Project Finance - A Guide For Contractors and EngineersDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Project Finance - A Guide For Contractors and Engineershazemdiab100% (1)

- Project Financing... NotesDocument21 pagesProject Financing... NotesRoney Raju Philip75% (4)

- Why Do Sponsors Use Project Finance?: 2. How Does Project Finance Create Value? Justify With An ExampleDocument3 pagesWhy Do Sponsors Use Project Finance?: 2. How Does Project Finance Create Value? Justify With An Examplekumsisa kajelchaNo ratings yet

- Unit-6:-Project FinanceDocument2 pagesUnit-6:-Project FinanceShradha KapseNo ratings yet

- Project Report - Project FinanceDocument10 pagesProject Report - Project Financeanon_266246835No ratings yet

- CH 7 Project FinancingDocument37 pagesCH 7 Project Financingyimer50% (2)

- Project FinanceDocument10 pagesProject FinanceElj LabNo ratings yet

- Arc612 Group 9Document33 pagesArc612 Group 9Stephen OlufekoNo ratings yet

- System of Project FinancingDocument13 pagesSystem of Project Financingmmaannttrraa100% (1)

- PDI Complete SlidesDocument151 pagesPDI Complete SlidesAbrar AkmalNo ratings yet

- Module 2: Financing of ProjectsDocument24 pagesModule 2: Financing of Projectsmy VinayNo ratings yet

- Project Finance: PURPA, The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act of 1978. Originally Envisioned AsDocument68 pagesProject Finance: PURPA, The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act of 1978. Originally Envisioned Assun_ashwiniNo ratings yet

- Features: Graham D Vinter, Project Finance, 3 Edition, 2006, Page No.1Document9 pagesFeatures: Graham D Vinter, Project Finance, 3 Edition, 2006, Page No.1ayush gattaniNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Project FinancingDocument2 pagesAdvantages of Project FinancingCultural RepresentativesNo ratings yet

- Project Finance AdvantagesDocument8 pagesProject Finance AdvantagesmaheshNo ratings yet

- Aydemir 2006Document128 pagesAydemir 2006Ankit SuriNo ratings yet

- Project FinancingDocument15 pagesProject FinancingAnkush RatnaparkheNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amDocument23 pagesLecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amSyeda Maira Batool100% (1)

- Financing of ProjectDocument13 pagesFinancing of ProjectADITYA SATAPATHYNo ratings yet

- Project Finance & Loan Syndication..EveningDocument21 pagesProject Finance & Loan Syndication..EveningRabina Akter JotyNo ratings yet

- Motivation For Project FinancingDocument15 pagesMotivation For Project FinancinghassanNo ratings yet