Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Writting Assignment: By: Joel Challa Pérez

Writting Assignment: By: Joel Challa Pérez

Uploaded by

Ladridos De Diogenes0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views14 pagesThe document provides guidance on writing effective writing assignments for students. It recommends (1) providing a thorough written description of the assignment and its purpose, (2) linking assignments to specific course objectives, and (3) specifying criteria for assessment. Longer assignments should be broken into stages, with outlines or drafts due before the final submission. Examples of successful student work can also help provide models. The goal is to make assignments clear and meaningful for learning.

Original Description:

Original Title

Writting assignment

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document provides guidance on writing effective writing assignments for students. It recommends (1) providing a thorough written description of the assignment and its purpose, (2) linking assignments to specific course objectives, and (3) specifying criteria for assessment. Longer assignments should be broken into stages, with outlines or drafts due before the final submission. Examples of successful student work can also help provide models. The goal is to make assignments clear and meaningful for learning.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views14 pagesWritting Assignment: By: Joel Challa Pérez

Writting Assignment: By: Joel Challa Pérez

Uploaded by

Ladridos De DiogenesThe document provides guidance on writing effective writing assignments for students. It recommends (1) providing a thorough written description of the assignment and its purpose, (2) linking assignments to specific course objectives, and (3) specifying criteria for assessment. Longer assignments should be broken into stages, with outlines or drafts due before the final submission. Examples of successful student work can also help provide models. The goal is to make assignments clear and meaningful for learning.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 14

Writting assignment

By: Joel Challa Pérez

How often have faculty members lamented the poor writing we get from our students?

Why can’t our students write an essay? a paragraph? a sentence? Sure, as a nation we

are grappling with increasing numbers of underprepared students, but maybe our

students aren’t entirely to blame. In a discussion of student writing, author and teacher

Donald Murray says, “A principal cause of poor writing received from students is the

assignment…far too many teachers blame the students for poor writing when the fault

lies with the teacher’s instructions—or lack of instructions.” (98)

So how does one write a good assignment that helps a student to be successful? Here

are some general principles

Provide and explain all assignments in writing

• Students need to have a thorough description of the task they will

complete and why they are completing it. In addition, provide as much

information as possible about format requirements, length (in pages or

word count), weighting of the assignment in the course, and grading

criteria. (See also my handout on creating rubrics.) Assignments should be

described in your syllabus or provided as a separate handout. Elements

suggested here can appear in any order that makes sense to you.

Link writing assignments to specific course

objectives

• In the description of the assignment, explain how this assignment relates

to and helps students achieve specific course or daily outcomes.

• Example This week you learned about bisques and chowders and their

thickening agents. In this assignment, you will record, analyze, and

compare your experience creating these two foods in a brief essay.

Specify the purpose and audience of the

assignment

• The more “real” the writing assignment is for the students, the better they will be able to

understand its usefulness and see its application to their learning. This information can

also increase critical thinking by asking students to analyze what their audiences already

know or need to know and how to present the information in their writing. The purpose

might be to explain, to analyze, to persuade, to summarize, to compare…

• The more “real” the writing assignment is for the students, the better they will be able to

understand its usefulness and see its application to their learning. This information can

also increase critical thinking by asking students to analyze what their audiences already

know or need to know and how to present the information in their writing. The purpose

might be to explain, to analyze, to persuade, to summarize, to compare…

Specify the assessment criteria

• If you have already created a grading rubric, provide that to your students

before they begin the assignment. If you have not yet created one, provide

a short list of those elements on which you will base the grading rubric,

describing for students what excellent work would look like. Below, I’ve

included a generic set of criteria you may want to consider, but it is

always good to tailor the language to your specific assignment (as you’ll

note in the sample assignment sheet included here)

Items in a list like this are normally

ordered in order from the most

important (or most heavily weighted)

to the least.

• Also include any statements that indicate a standard below which assignments

will not be acceptable.

Try out a variety of kinds of writing

assignments (short v. long, informal v. formal)

Writing assignments do not all have to be formal, lengthy essays to be effective for student learning.

Consider using several shorter assignments, such as paragraphs, journal entries, or short essays.

The shorter the assignment, however, the more focused it should be.

• Note: 300 words is about one page of text in a paper that is double spaced with 12-

point font and 1” margins on all sides. Remind students that paragraphs should be

well constructed around a main idea (typically presented in a topic sentence) and

should contain enough detail to illustrate or support he point being made. Journal

entries are typically low-stakes assignments in which the audience is the writer and

the instructor. Candid and thorough discussion of the assigned topic are typically the

bases for grading in journal assignments. Longer assignments are normally more

formal and often incorporate outside sources of information (from research or

interviews). Anytime sources are used, students should be expected to document them

in an accepted academic format (of your choice).

Organize longer projects in stages

• Students in writing classes learn to work on their writing as a process, but once they

get to nonwriting classes, they sometimes begin an assignment the night before it is

due and revert to the onedraft-is-plenty approach to writing. Consider asking students

turn at least some their process work in. You might ask for an outline or a draft a week

or two before the final assignment is due. You do not have to grade these, but can give

them a quick glance and check mark in class or you could ask students to spend 15-30

minutes of class time offering feedback on each other’s work. Providing a few points

of completion credit helps the student see this as an important stage of the assignment.

(Note: I find that bonus credit does not usually work for these kinds of assignments,

as too many students opt out of bonus points for such tasks.)

Provide examples of successful work

• Whenever possible, show student work (for which you have permission to

share) completed by previous students that demonstrates a successful

assignment. Post them as a PDF in Blackboard, or show one on the screen

in class. Discuss with your students what made this assignment successful

as well as anything that could make it more successful. Teaching this

assignment for the first time? Tell your student you will be looking for

model papers to use for future classes, and when you see one, ask the

student’s permission to share it at a later date.

Redaction

You might also like

- Erin Loyd - RCIII BibliographyDocument2 pagesErin Loyd - RCIII BibliographyErin Loyd100% (1)

- Digital Unit Plan TemplateDocument4 pagesDigital Unit Plan Templateapi-219209806No ratings yet

- Brussels and BradshawDocument7 pagesBrussels and BradshawSoumendu Mukhopadhyay50% (2)

- Creating Writing Assignments To Promote Student SuccessDocument6 pagesCreating Writing Assignments To Promote Student SuccessRai Ahsan KharalNo ratings yet

- Low Stakes Writing Assignments: Centre For Teaching ExcellenceDocument6 pagesLow Stakes Writing Assignments: Centre For Teaching ExcellenceChristian ChoquetteNo ratings yet

- Creating Effective Peer Review Groups To Improve Student WritingDocument5 pagesCreating Effective Peer Review Groups To Improve Student WritingCristina PérezNo ratings yet

- Activities To Practice Writing Thesis StatementsDocument5 pagesActivities To Practice Writing Thesis Statementsafayememn100% (2)

- K00369 - 20191007160141 - Panduan Menulis Tugasan HSA3043Document29 pagesK00369 - 20191007160141 - Panduan Menulis Tugasan HSA3043Chicha TinggiNo ratings yet

- Activities To Teach Thesis StatementsDocument7 pagesActivities To Teach Thesis StatementsBuyAPaperOnlineUK100% (2)

- Exercises On Writing A Thesis StatementDocument6 pagesExercises On Writing A Thesis StatementLiz Adams100% (2)

- Maculada, Jodi Marie Beed 3-cDocument7 pagesMaculada, Jodi Marie Beed 3-cMa Lourdes Abada MaculadaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Guide: Writing Lesson PlansDocument31 pagesTeaching Guide: Writing Lesson PlansKa Lok LeeNo ratings yet

- Extended Writing - EnGDocument13 pagesExtended Writing - EnGchanteprinsloo1No ratings yet

- LCT-Assignment Design Tip SheetDocument10 pagesLCT-Assignment Design Tip SheetLaiPeiyeeNo ratings yet

- Thesis LessonDocument8 pagesThesis Lessonaouetoiig100% (2)

- Thesis Statement Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Multiple Choice QuestionsHowToWriteMyPaperOmaha100% (2)

- Coursework FormatDocument4 pagesCoursework Formatf5dbf38y100% (2)

- Your CourseworkDocument6 pagesYour Courseworkxdkankjbf100% (2)

- Thesis Statement Activities Middle SchoolDocument6 pagesThesis Statement Activities Middle Schoolcindywootenevansville100% (2)

- How To Teach Middle School Students To Write A Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesHow To Teach Middle School Students To Write A Thesis Statementgjbyse71100% (2)

- Coursework What Does It MeanDocument6 pagesCoursework What Does It Meandthtrtlfg100% (1)

- Teaching of Reading and Writing Skills (Chandran) PDDocument21 pagesTeaching of Reading and Writing Skills (Chandran) PDChandran Abraham EbenazerNo ratings yet

- Content of CourseworkDocument5 pagesContent of Courseworkafayememn100% (1)

- Sample Thesis AssessmentDocument4 pagesSample Thesis AssessmentCheapCustomPapersPaterson100% (2)

- Reading Group Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesReading Group Lesson Planapi-477255988No ratings yet

- Lesson Plans Teaching Thesis StatementsDocument5 pagesLesson Plans Teaching Thesis Statementsruthuithovensiouxfalls100% (2)

- Whats CourseworkDocument6 pagesWhats Courseworkusjcgcnbf100% (2)

- UWC Handouts ReadingessaypromptsDocument3 pagesUWC Handouts ReadingessaypromptsdNo ratings yet

- Background Work: Clarify The Rationale and Context For The CourseDocument10 pagesBackground Work: Clarify The Rationale and Context For The CoursesrinivasanaNo ratings yet

- Steps For Syllabus Design: Developing A Course SyllabusDocument8 pagesSteps For Syllabus Design: Developing A Course SyllabusRt SaragihNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Lesson Plan PDFDocument5 pagesThesis Statement Lesson Plan PDFafknekkfs100% (2)

- How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?Document7 pagesHow Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?ptc clickerNo ratings yet

- Generic Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesGeneric Lesson Plan TemplateIP GNo ratings yet

- Good Coursework PhrasesDocument6 pagesGood Coursework Phrasesf0jimub1lef2100% (2)

- Coursework Plan ExampleDocument5 pagesCoursework Plan Exampleafjwrcqmzuxzxg100% (2)

- Esl Thesis Statement ExercisesDocument6 pagesEsl Thesis Statement Exercisesafcnuaacq100% (1)

- How To Start CourseworkDocument4 pagesHow To Start Courseworkbcqta9j6100% (2)

- Thesis Writing Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesThesis Writing Lesson Planashleydavisshreveport100% (2)

- Speaking Of: Designing CoursesDocument5 pagesSpeaking Of: Designing CoursesHappy DealNo ratings yet

- Nunan, Principles For Teaching WritingDocument5 pagesNunan, Principles For Teaching WritingDewi Rosiana100% (3)

- Practice Creating Thesis Statements WorksheetDocument6 pagesPractice Creating Thesis Statements Worksheetfc5wsq30100% (2)

- Writing A Research Paper Lesson Plan Middle SchoolDocument7 pagesWriting A Research Paper Lesson Plan Middle Schoolfzg9e1r9No ratings yet

- Importance of CourseworkDocument4 pagesImportance of Courseworkf5d17e05100% (2)

- Writing How To WriteDocument27 pagesWriting How To WriteashishsahofficialNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Thesis Statement Middle SchoolDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Thesis Statement Middle Schoolqpftgehig100% (2)

- Lesson Plan For Research PaperDocument5 pagesLesson Plan For Research Paperaflbskroi100% (1)

- Independent Practice Samples TESOLDocument2 pagesIndependent Practice Samples TESOLMarcela TintinagoNo ratings yet

- Teaching GuideDocument20 pagesTeaching GuideSilvia Cecilia SosaNo ratings yet

- Grading Rubric For Research Paper Middle SchoolDocument4 pagesGrading Rubric For Research Paper Middle Schooljsmyxkvkg100% (1)

- What Does Completed Coursework MeanDocument7 pagesWhat Does Completed Coursework Meanswqoqnjbf100% (2)

- Lesson Plan Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Thesis Statementbethanyrodriguezmanchester100% (2)

- A.how To Write Introductions and ConclusionsDocument4 pagesA.how To Write Introductions and ConclusionsashishsahofficialNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Middle School WorksheetsDocument6 pagesThesis Statement Middle School WorksheetsPayingSomeoneToWriteAPaperSingapore100% (2)

- Assignment: Practice Teaching NoDocument22 pagesAssignment: Practice Teaching NoKiranNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Peer Review RubricDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Peer Review RubricipkpzjbkfNo ratings yet

- Which Part of The Writing Process Includes Developing A Thesis StatementDocument6 pagesWhich Part of The Writing Process Includes Developing A Thesis Statementbk156rhq100% (1)

- Exercises On Writing A Good Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesExercises On Writing A Good Thesis Statementobyxqnief100% (2)

- Expository Writing Thesis ExamplesDocument6 pagesExpository Writing Thesis Examplesjessicahillknoxville100% (2)

- Pgce Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPgce Dissertation TitlesWriteMyThesisPaperManchester100% (1)

- Essay Thesis TemplateDocument6 pagesEssay Thesis Templatestephaniekingmanchester100% (2)

- Coursework Writing FormatDocument6 pagesCoursework Writing Formatguj0zukyven2100% (2)

- Introduction To Arabic Egyptian Arabic For First Year Students 1689797941Document424 pagesIntroduction To Arabic Egyptian Arabic For First Year Students 168979794117st03No ratings yet

- Tle 8-Beautycare-Q4-M1Document10 pagesTle 8-Beautycare-Q4-M1Gretchen Sarmiento Cabarles AlbaoNo ratings yet

- Lauren Carew ResumeDocument1 pageLauren Carew ResumeLauren CarewNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Ece Writing AssignmentsDocument1 pageGuidelines For Ece Writing AssignmentsChrismoonNo ratings yet

- Grades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log School: Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates & Time QuarterDocument5 pagesGrades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log School: Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates & Time QuarterJohnCzyril Deladia DomensNo ratings yet

- Article WritingDocument3 pagesArticle WritingAditi TiwariNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument4 pagesClinical Reasoningapi-351971578No ratings yet

- Masterlist: Transfer in & Balik-Aral LearnersDocument2 pagesMasterlist: Transfer in & Balik-Aral LearnersChaa MontillaNo ratings yet

- FMS 825 Research MethodologyDocument125 pagesFMS 825 Research Methodologysunkanmi hebraheemNo ratings yet

- B.SC - Food Science NutritionDocument104 pagesB.SC - Food Science NutritionKathyayani DNo ratings yet

- GGSIPU Application Form PDFDocument1 pageGGSIPU Application Form PDFNarsingh Das AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Teaching Organ in An Holistic Manner LaverDocument6 pagesTeaching Organ in An Holistic Manner Lavermanuel1971No ratings yet

- Certificate of Participation Imee Loren S. Abonales: Jaclyn Joyce T. Bascar Gertrudes Anastacia D. Lopez, Ed. DDocument35 pagesCertificate of Participation Imee Loren S. Abonales: Jaclyn Joyce T. Bascar Gertrudes Anastacia D. Lopez, Ed. DImee Loren AbonalesNo ratings yet

- The Work of The Forensic PhoneticianDocument3 pagesThe Work of The Forensic PhoneticianKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- JDMProSystemRequirements Boeing Jeppesen JDMDocument3 pagesJDMProSystemRequirements Boeing Jeppesen JDMtechgeekvnNo ratings yet

- Etech Teenage PregnancyDocument13 pagesEtech Teenage PregnancyIrish Siagan AquinoNo ratings yet

- Interviews: (Informative Communication Example)Document29 pagesInterviews: (Informative Communication Example)Francis RaagasNo ratings yet

- UNLV/Department of Teaching & Learning Elementary Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesUNLV/Department of Teaching & Learning Elementary Lesson Plan Templateapi-438880639No ratings yet

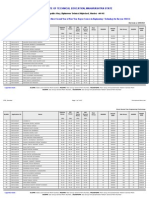

- Provisional Merit List DSE OverAll2010Document1,107 pagesProvisional Merit List DSE OverAll2010Sidd SalNo ratings yet

- Tiempo FuturoDocument3 pagesTiempo FuturoMartha Lucía PeláezNo ratings yet

- 10 Maths XamIdeaDocument308 pages10 Maths XamIdeafathur88% (16)

- Alkitab Journal For Human SciencesDocument71 pagesAlkitab Journal For Human SciencesAmirHB79No ratings yet

- E. Rukmangadachari - Engineering Mathematics - Volume - 1-Pearson Education (2009)Document561 pagesE. Rukmangadachari - Engineering Mathematics - Volume - 1-Pearson Education (2009)Atharv Aggarwal100% (1)

- PT3 Science DSKP + KSSM Notes - Exam Tips UPSR PT3 SPM 2019 - 2020Document4 pagesPT3 Science DSKP + KSSM Notes - Exam Tips UPSR PT3 SPM 2019 - 2020anon_4133945530% (1)

- Harrison-Chen-NegNewark Invitational 2022-Round1Document15 pagesHarrison-Chen-NegNewark Invitational 2022-Round1Richard NguyenNo ratings yet

- Shape It! Level 2Document12 pagesShape It! Level 2ive14_No ratings yet

- SHS WORKBOOK - ENTREP Session 1Document5 pagesSHS WORKBOOK - ENTREP Session 1devriel carsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document12 pagesChapter 3Kenneth Roy MatuguinaNo ratings yet