Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 viewsThe Second Group

The Second Group

Uploaded by

farhan1. The document discusses the history of Muslim and Christian relations in Ambon, Indonesia, including the influence of separatist movements, transmigration policies, and the Pela tradition of alliance between communities.

2. It describes how Soekarno's transmigration program in the 1950s moved Muslims from other parts of Indonesia to Ambon to reduce the Christian majority and threats of separatism, though he also accommodated Christians in local government.

3. The oldest Pela ceremony formed alliances between communities to reduce segregation from colonial policies, though its origins are unclear with both factual and mythological explanations existing. It became an interreligious treaty after Christianization of parts of Ambon.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- How To Make 10K A Month With Dropshipping Ebook PDFDocument21 pagesHow To Make 10K A Month With Dropshipping Ebook PDFhappy100% (1)

- Azazel PDFDocument175 pagesAzazel PDFDevon MonstratorNo ratings yet

- Sea Nomads 1Document12 pagesSea Nomads 1qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Learning Agreement Traineeships Form Nou 2016-2017-1Document5 pagesLearning Agreement Traineeships Form Nou 2016-2017-1florin31No ratings yet

- The Second GroupDocument18 pagesThe Second GroupfarhanNo ratings yet

- TASKDocument7 pagesTASKfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelDocument9 pagesThe Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelfarhanNo ratings yet

- Acehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterDocument31 pagesAcehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterTeuku Fadli SaniNo ratings yet

- Moro PiracyDocument20 pagesMoro PiracyEmmanuel LoyaNo ratings yet

- RRLFINALDocument79 pagesRRLFINALAdrienne Margaux DejorasNo ratings yet

- African Studies 2003 ChiefsmigrantsethnicityarticleDocument27 pagesAfrican Studies 2003 ChiefsmigrantsethnicityarticleThabang MasekwamengNo ratings yet

- The "Ethnic" in Indonesia's Communal Conflicts: Violence in Ambon, Poso and SambasDocument3 pagesThe "Ethnic" in Indonesia's Communal Conflicts: Violence in Ambon, Poso and SambasHanifahNo ratings yet

- Malay BruneiDocument20 pagesMalay Bruneisudang johnnyNo ratings yet

- The Khoikhoi 203Document7 pagesThe Khoikhoi 203iyaomolere oloruntobaNo ratings yet

- 5902-Article Text-7829-1-10-20090319 PDFDocument18 pages5902-Article Text-7829-1-10-20090319 PDFReza Maulana HikamNo ratings yet

- 2 CulturalPluralismReinventingAzyumardiDocument10 pages2 CulturalPluralismReinventingAzyumardiIcaios AcehNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Migration On The Development and Spreading of Bantu LanguagesDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Migration On The Development and Spreading of Bantu LanguagesavduongNo ratings yet

- Bbilo Nnopa ProposalDocument18 pagesBbilo Nnopa ProposalMelese LegeseNo ratings yet

- Ndebele Shona Relations Were Cordial PDFDocument2 pagesNdebele Shona Relations Were Cordial PDFNyasha Mutamehama91% (11)

- I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ke Ola I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ka MakeDocument9 pagesI Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ke Ola I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ka MakeZen. Ni100% (2)

- History of Philippine Foreign Policy Revised - 075901Document38 pagesHistory of Philippine Foreign Policy Revised - 075901Keiren Faith BaylonNo ratings yet

- HIS203 Complete Note-WPS OfficeDocument8 pagesHIS203 Complete Note-WPS OfficeONAOLAPONo ratings yet

- History of Ethiopia & The Horn Unit 5Document57 pagesHistory of Ethiopia & The Horn Unit 5Suraphel BirhaneNo ratings yet

- Biologi - 5037Document4 pagesBiologi - 5037Ilham Taufik MunandarNo ratings yet

- People's Way of Life Is Commonly Referred To As Culture.Document14 pagesPeople's Way of Life Is Commonly Referred To As Culture.Jhoy Valerie Foy-awonNo ratings yet

- A.Abubakar-muslim Philippines Sulus Muslim Christian Contradictions Mindanao Crisis PDFDocument17 pagesA.Abubakar-muslim Philippines Sulus Muslim Christian Contradictions Mindanao Crisis PDFRina IsabelNo ratings yet

- Hjui 9242Document4 pagesHjui 9242rivandiekaputraNo ratings yet

- Eminov 2000Document37 pagesEminov 2000pycuNo ratings yet

- The Indus VaRley Civilization and Early TibetDocument20 pagesThe Indus VaRley Civilization and Early TibetTenzin SopaNo ratings yet

- Xhosa PeopleDocument7 pagesXhosa PeopleManzini MbongeniNo ratings yet

- The Eastern Nyika: Preliminary Notes On History, Ethnography and LanguageDocument14 pagesThe Eastern Nyika: Preliminary Notes On History, Ethnography and LanguageMartin WalshNo ratings yet

- Henry Assessed Hamattan Corrected ReviewDocument20 pagesHenry Assessed Hamattan Corrected ReviewHenry Gyang MangNo ratings yet

- Apartheid In South Africa - Origins And ImpactFrom EverandApartheid In South Africa - Origins And ImpactRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Full TextDocument30 pagesFull TextbethgovoNo ratings yet

- HANSON The Making of The Maori PDFDocument14 pagesHANSON The Making of The Maori PDFMiguel Aparicio100% (1)

- Buddhaputra and BhumiputraDocument25 pagesBuddhaputra and BhumiputramahamamaNo ratings yet

- Zakaria - Landscapes and Conversions During The Padri WarsDocument40 pagesZakaria - Landscapes and Conversions During The Padri WarsDesi SariNo ratings yet

- Jdhcvda 4099Document17 pagesJdhcvda 4099Shop PeNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Berry's Acculturation FrameworkDocument12 pagesTheorizing Berry's Acculturation FrameworkTrudy DamenNo ratings yet

- Paideusis - Journal For Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Studies Volume 1 1998 ARTICLES (N1ae)Document13 pagesPaideusis - Journal For Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Studies Volume 1 1998 ARTICLES (N1ae)Whodabanger ThebangerNo ratings yet

- The Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDocument44 pagesThe Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDafner Siagian100% (1)

- GST 113 Lecture 1, 2Document14 pagesGST 113 Lecture 1, 2Solomon BinutuNo ratings yet

- Hidden Land of PemakoDocument32 pagesHidden Land of Pemakoneuweil1100% (1)

- The Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicDocument14 pagesThe Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicCarola LalalaNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Ethnicity in Southeast AsiaDocument16 pagesNationalism and Ethnicity in Southeast Asiacrystalgarcia0329No ratings yet

- Historic Aboriginal Pottery at Stono Plantation: A Descriptive Summary by Ronald W. AnthonyDocument13 pagesHistoric Aboriginal Pottery at Stono Plantation: A Descriptive Summary by Ronald W. AnthonySECHSApapersNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Politics, Development and Identity in Peninsular Malaysia: The Orang Asli and The Contest For ResourcesDocument18 pagesIndigenous Politics, Development and Identity in Peninsular Malaysia: The Orang Asli and The Contest For ResourcesThareq Akmal HibatullahNo ratings yet

- Ardes04 - T'boliDocument45 pagesArdes04 - T'boliHANNIE BROQUEZANo ratings yet

- Oromo HistoryDocument4 pagesOromo Historymuzayanmustefa9No ratings yet

- Muller LDancinggoldenstoolsDocument27 pagesMuller LDancinggoldenstoolsudehgideon975No ratings yet

- AJISS 26!3!5 Article 5 Islam As An Ideology of Resistance Mohammed HassenDocument24 pagesAJISS 26!3!5 Article 5 Islam As An Ideology of Resistance Mohammed HassenUsme OnispireNo ratings yet

- Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland ManDocument21 pagesWiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland ManMaria Luísa LucasNo ratings yet

- HANSON - The Making of The MaoriDocument14 pagesHANSON - The Making of The MaoriRodrigo AmaroNo ratings yet

- History Extra PDFDocument13 pagesHistory Extra PDFblenNo ratings yet

- Tomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Document29 pagesTomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Diego MarquesNo ratings yet

- Maori History and ProtestDocument18 pagesMaori History and ProtestHelgeSnorriNo ratings yet

- Makhubo HisvDocument11 pagesMakhubo HisvTHAPELO MAKHUBONo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism in Mindanao, Philippines: The Role of Ethnicity in External and Internal HegemonyDocument20 pagesMulticulturalism in Mindanao, Philippines: The Role of Ethnicity in External and Internal HegemonyAaliyahNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Regionalism in Colonial IndonesiaDocument22 pagesNationalism and Regionalism in Colonial IndonesiaGeoNo ratings yet

- HDR2005 Brown, Graham - Horizontal Inequalities, Ethnic Separatism, and Violent Conflict: The Case of Aceh, IndonesiaDocument11 pagesHDR2005 Brown, Graham - Horizontal Inequalities, Ethnic Separatism, and Violent Conflict: The Case of Aceh, IndonesiaEmma 'Emmachi' AsombaNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Marronage, The Power of Language, and Creole GenesisDocument8 pagesSpiritual Marronage, The Power of Language, and Creole GenesisJason BurrageNo ratings yet

- Maribeth Errb-Catholic and Identity in ManggaraiDocument30 pagesMaribeth Errb-Catholic and Identity in ManggaraiEdward AngimoyNo ratings yet

- Education, Recognition, and The Sami People of NorwayDocument19 pagesEducation, Recognition, and The Sami People of NorwayJonas JakobsenNo ratings yet

- The 7th Meeting AssignmentDocument1 pageThe 7th Meeting AssignmentfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelDocument9 pagesThe Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelfarhanNo ratings yet

- TASKDocument7 pagesTASKfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Second GroupDocument18 pagesThe Second GroupfarhanNo ratings yet

- Blossoms of The Savannah Kcse Essay Questions and AnswersDocument32 pagesBlossoms of The Savannah Kcse Essay Questions and AnswersMichael Mike100% (1)

- SelfEmploymentBook PDFDocument198 pagesSelfEmploymentBook PDFexecutive engineerNo ratings yet

- GS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormDocument2 pagesGS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormJP De La PeñaNo ratings yet

- Using Self-Reliance As A Ministering Tool (Revised June 13, 2018)Document18 pagesUsing Self-Reliance As A Ministering Tool (Revised June 13, 2018)joseph malawigNo ratings yet

- English For Practical UseDocument4 pagesEnglish For Practical Usenursaida100% (1)

- Financial Status AffectingDocument9 pagesFinancial Status AffectingChen ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- BFN Amphitheater Lineup 2023Document2 pagesBFN Amphitheater Lineup 2023TMJ4 NewsNo ratings yet

- English QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesEnglish QuestionnairePamelaCindyTumuyu80% (15)

- CIV PRO DigestDocument54 pagesCIV PRO DigestbcarNo ratings yet

- DH 2011 1008 Part A DCHB KishanganjDocument594 pagesDH 2011 1008 Part A DCHB Kishanganjaditi kaviwalaNo ratings yet

- Arts in Muslim SouthDocument12 pagesArts in Muslim SouthKem Paulo QueNo ratings yet

- 27.0 - Confined Spaces v3.0 EnglishDocument14 pages27.0 - Confined Spaces v3.0 Englishwaheed0% (1)

- Corpuz vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesCorpuz vs. PeopleAli NamlaNo ratings yet

- Errors About Detective StoriesDocument3 pagesErrors About Detective StoriesAgustin IssidoroNo ratings yet

- AIFs in GIFT IFSC Booklet October 2020Document12 pagesAIFs in GIFT IFSC Booklet October 2020Karthick JayNo ratings yet

- Economy - Indian EconomicsDocument382 pagesEconomy - Indian EconomicshevenpapiyaNo ratings yet

- Presentation To IEEDocument17 pagesPresentation To IEEomairakhtar12345No ratings yet

- Philippine School of Business Administration R. Papa ST., Sampaloc, ManilaDocument12 pagesPhilippine School of Business Administration R. Papa ST., Sampaloc, ManilaNaiomi NicasioNo ratings yet

- Publishing and Disseminating Dalit Literature: Joshil K. AbrahamDocument8 pagesPublishing and Disseminating Dalit Literature: Joshil K. AbrahamkalyaneeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Quiz 1Document3 pagesChapter 4 Quiz 1yash_28No ratings yet

- Quarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberDocument1 pageQuarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberJenny Lyn MasgongNo ratings yet

- History of PlumbingDocument2 pagesHistory of PlumbingPaola Marie JuanilloNo ratings yet

- Compound Complex SentenceDocument32 pagesCompound Complex SentenceReynaldo SihiteNo ratings yet

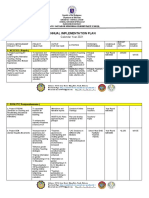

- Annual Implementation Plan: Calendar Year 2021Document5 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan: Calendar Year 2021Guia Marie Diaz BriginoNo ratings yet

- 78903567-Garga by GargacharyaDocument55 pages78903567-Garga by GargacharyaGirish BegoorNo ratings yet

- The Thin Red Line: European Philosophy and The American Soldier at WarDocument8 pagesThe Thin Red Line: European Philosophy and The American Soldier at Warnummer2No ratings yet

- Case Digest - Carpio VS Sulu Resources Development CorporationDocument3 pagesCase Digest - Carpio VS Sulu Resources Development Corporationfred rhyan llausasNo ratings yet

The Second Group

The Second Group

Uploaded by

farhan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views13 pages1. The document discusses the history of Muslim and Christian relations in Ambon, Indonesia, including the influence of separatist movements, transmigration policies, and the Pela tradition of alliance between communities.

2. It describes how Soekarno's transmigration program in the 1950s moved Muslims from other parts of Indonesia to Ambon to reduce the Christian majority and threats of separatism, though he also accommodated Christians in local government.

3. The oldest Pela ceremony formed alliances between communities to reduce segregation from colonial policies, though its origins are unclear with both factual and mythological explanations existing. It became an interreligious treaty after Christianization of parts of Ambon.

Original Description:

Original Title

THE SECOND GROUP (2)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. The document discusses the history of Muslim and Christian relations in Ambon, Indonesia, including the influence of separatist movements, transmigration policies, and the Pela tradition of alliance between communities.

2. It describes how Soekarno's transmigration program in the 1950s moved Muslims from other parts of Indonesia to Ambon to reduce the Christian majority and threats of separatism, though he also accommodated Christians in local government.

3. The oldest Pela ceremony formed alliances between communities to reduce segregation from colonial policies, though its origins are unclear with both factual and mythological explanations existing. It became an interreligious treaty after Christianization of parts of Ambon.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views13 pagesThe Second Group

The Second Group

Uploaded by

farhan1. The document discusses the history of Muslim and Christian relations in Ambon, Indonesia, including the influence of separatist movements, transmigration policies, and the Pela tradition of alliance between communities.

2. It describes how Soekarno's transmigration program in the 1950s moved Muslims from other parts of Indonesia to Ambon to reduce the Christian majority and threats of separatism, though he also accommodated Christians in local government.

3. The oldest Pela ceremony formed alliances between communities to reduce segregation from colonial policies, though its origins are unclear with both factual and mythological explanations existing. It became an interreligious treaty after Christianization of parts of Ambon.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 13

SECOND GROUP

The Dynamics of Muslim

and Christian Relations in

Ambon, Eastern Indonesia

MEMBERS OF GROUP TWO :

1. Sartika Rahangmetan

2. Surianti Loupatan

3. Selfi Rabrusun

4. Siti Fatima Rahantan

5. Anisa Fatsey

6. M. Ali Farhan Marasabessy

continued from page two

. In 1950, the Republic of South Moluccas (RMS) broke away,

attempting to make the Moluccas separate and independent

from Indonesia. Finally, the Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia

(NKRI, Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia) defeated the

RMS. Subsequently, separatists came under pressure as the

central government of Indonesia set out to create a more

balanced population of Muslims and Christians. The Christian

majority in the Moluccas was seen by central government as

posing a separatist threat.

Certainly, the RMS separatist movement has had a long historical influence on

Muslim and Christian relations. Soekarno's government saw the movement as

a threat to national unity. Soekarno began a transmigration program where by

people from the heavily populated Java, Madura, Bali and Lombok regions

were moved to the Moluccas and other islands (Hardjono, 1977, p. 25-26).

Soekarno's transmigration policy was projected as supporting national

security, as promoting national integration, and as remedying Indonesia's

uneven population distribution (Goss, 1992, p. 87-88). Sainz called this a

policy of "Javanisation" of the Outer Islands as [a] means, to achieve "national

unity" against separatist tendencies' (1982, p. 10). Certainly, this policy served

to reduce the emergence of separatist movements in the Moluccas, by

assimilating national traditions and by balancing the Christian and Muslim

populations, as most transmigrants were Muslims. However, Soekano also

accommodated Christians by placing them in positions of political panel in the

local government.

The Dynamic of Pela in the Pre-

Colonial and Colonial Periods

The population of the Ambonese islands has been segregated since

the pre-colonial period. As stated previously, the Muslims of Ternate

and Tidore had successfully Islamised the Leihitu peninsula.

However, in the Leitimor (later Ambon city) region, the inhabitants

were originally animist-Hindus. The Portuguese converted the

Leitimor Hindus to Catholicism and the Dutch converted the rest of

the Hindus and a small number of Muslims and Catholics to

Protestantism. Herein are the early roots of segregation in the

Ambonese islands. The Dutch reinforced this segregation with their

discriminatory policies against certain groups in the islands.

The impact of segregation was reduced, however, by a treaty arrangement

between the different communities that allowed friendships to be formed. This

treaty was based on the Pela tradition. 'Pela' means 'brother' or 'trusted friend'

and is a word originally from the Hoamoal peninsula (Seram) and adopted into

the Ambonese language. The original meaning of Pela was 'to be finished'

(Bartels, 1978, p. 58). Pela tradition can be divided into three categories: Pela

Tuni or Pela Kerns', Pela Tempat Sirih; and, Pela Gandong. Pela Tuni has two

categories: Pela Tumpah Darah and Pela Batu Karang (Huwae, 1995, p. 79).

The further analysis will focus on the Pela Gandong tradition, which was

prominent in discussion during reconciliation attempts in 1999-2002. The Pela

Gandong tradition is an alliance of two or more people related by marriage, in

which they agree to help each other based on family ties. For example, the

Pela among the regions of the Tamilou, Siri-Sori and Hutumuri2 was originally

between three brothers from the village of Hatumeten on the island of Ceram,

who decided to be in alliance after migrating to their new places in the three

villages mentioned (Huwae, 1995, p. 80-81).

Ironically, the oldest and existing Pela ceremony was not found in

Ceram, but in the mountains of the Leitimur peninsula in Ambon. It

was supposed that the Ceramese had adopted the tradition during a

time of turbulence between Ambonese communities (Bartels, 1978,

p. 80). The actual origins of Pela are blurred and there is a lack of

strong historical evidence. According to Bartels, it was the subject of

speculation in early European writings and not part of 'native

explanations' (1978, p. 67). Furthermore, Bartels states that:

Ambonese explanations of the origin of pela ... range ... from factual

speculations to semimythical accounts. The first are based on

historical factors but their elaboration is hampered by the still

insufficient access of Ambonese to written historical records. In

Respect to the latter, it must be remembered that Ambonese, like

other people, are ... curious about past events and their chronology.

In such circumstances, history often becomes a justification [for] the

present situation and [a] basis lor ideology (Bartels, 1978, p. 72).

Ambonese explanations of the origin of pela ...

range ... from factual speculations to semimythical

accounts. The first are based on historical factors

but their elaboration is hampered by the still

insufficient access of Ambonese to written historical

records. In respect to the latter, it must be

remembered that Ambonese, like other people, are

... curious about past events and their chronology.

In such circumstances, history often becomes a

Justification [for] the present situation and [a] basis

lor ideology (Bartels, 1978, p. 72).

The earliest Pela tradition was given brief mention in Ridjali's Hikayat

Tanah Hitu, which Bartels (1978) considers to be the oldest written

source discussing this alliance. In 1495, there was an unbreakable tie

between the King of Ternate, Zainul abedien, and Pati Tuban, the

ruler of Hitu kingdom. They declared by a ceremonial oath that they

Along with their territories would have an eternal friendship and

alliance. This pela was merely a promulgation of the raja (king) of

Hitumessen, which was accepted by the Hitu people (Bartels, 1978,

p. 73). However, during the Dutch period, the Hitu with the support of

the Ternate kingdom defended their interests in the face of Dutch

pressure. The alliance was pragmatically employed by both rulers to

preserve their political and economic interests. Subsequently,

differences in policy regarding the Dutch arose between them.

Ternate adopted a non-aggression approach toward the Dutch. The

Hitu lost their ties with the Ternate kingdom.

The Pela was also meant as a treaty between

Muslims and Christians. It was probably not

originally an interreligious treaty, but because of the

subsequent Christianisation of parts of the

Ambonese islands by the Portuguese and Dutch,

the treaty became an inter-religious one. This was a

crucial development in the Pela tradition, especially

in the first five or six decades after the Dutch arrival

(1605-1656). Many of the Pela alliances entered

into between Muslims, non-Muslims and pagans

have continued until today (Bartels, 1978, p. 15).

The New Order Centralisation of

Development and Politics

During the New Order period, the Pela Gandong tradition was merely a symbol of

Religious harmony in the Ambonese islands. It was promoted in tourism brochures by a

National government proud of the harmony between multi-ethnic and multi-religious

Indonesians. However, more transmigrants were coming to the Moluccas under the

sponsorship of the central government so as to foster development, national unity and

national defense and security (Goss, 1992, p. 88). Many came voluntarily from Java,

Sumatra and Sulawesi to the transmigration projects in Ceram, other regions in the

Moluccas and to the capital city of Ambon. In the capital, the proportion of Christians in

the population changed from 60 per cent in the 1970s to 52 per cent in the 1990s. This

was the result not only of a rise in the number of new Butonese, Buginese, Makassarese

and Javanese migrants coming to the city, but was also the result of an increase in

number of Ambonese Christians emigrating to Java after facing difficulties in finding work

and making a living during the 1990s. Of course, non-indigenous Ambonese did not hold

to the Pela tradition, which continued to influence the thought of young indigenous

Ambonese. Transmigration and the growing urbanisation of indigenous Ambonese were

important factors in bringing about a change in Ambonese culture during the 1990s.

Ambonese culture was also drastically changed by

of the New Order's centralisation of government.

The traditional local leadership was remodeled

along Javanese lines based around the concept of

the lurah (head of village). In the longer term, the

king and traditional leaders lost privileges and the

respect of their communities. According to New

Order policy, the only official political ideology was

that of Pancasila. Soeharto succeeded in

suppressing the power of local political figures, by

eliminating the essence of their political identity and

the basis for their power.

However, local cultural expressions resurged after the fall of

Soeharto. President Habibie's government gave more opportunities

for local politics and local political identities when the government

introduced a regional autonomy policy. Unfortunately, the euphoria of

regional autonomy was to result in the strengthening of the

indigenous community against migrants. Thus, the Arnbon conflict

can be seen as the product of regional political dynamics in this

Period of transition in Indonesian politics. In the city of Ambon, most

Muslims live in the coastal areas around Batu Merah. They are

migrants from South and Southeast Sulawesi, Java and Sumatra.

Muslims also came to live in the middle of Christian areas in Ambon.

As has been indicated, during the Colonial and the Soekarno periods

Leitimor became a Christian region. However, the structure of the

population changed once the New Order introduced its transmigration

policy and open up Ambon city for Muslim urban settlement.

Furthermore, the central government openly pushed this development as part

of its ambitious transmigration policy.

THANK YOU

FOR YOUR

ATTENTION

AND

GOOD LUCK

;)

You might also like

- How To Make 10K A Month With Dropshipping Ebook PDFDocument21 pagesHow To Make 10K A Month With Dropshipping Ebook PDFhappy100% (1)

- Azazel PDFDocument175 pagesAzazel PDFDevon MonstratorNo ratings yet

- Sea Nomads 1Document12 pagesSea Nomads 1qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Learning Agreement Traineeships Form Nou 2016-2017-1Document5 pagesLearning Agreement Traineeships Form Nou 2016-2017-1florin31No ratings yet

- The Second GroupDocument18 pagesThe Second GroupfarhanNo ratings yet

- TASKDocument7 pagesTASKfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelDocument9 pagesThe Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelfarhanNo ratings yet

- Acehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterDocument31 pagesAcehnese Culture(s) : Plurality and Homogeneity.: Prof. Dr. Susanne SchröterTeuku Fadli SaniNo ratings yet

- Moro PiracyDocument20 pagesMoro PiracyEmmanuel LoyaNo ratings yet

- RRLFINALDocument79 pagesRRLFINALAdrienne Margaux DejorasNo ratings yet

- African Studies 2003 ChiefsmigrantsethnicityarticleDocument27 pagesAfrican Studies 2003 ChiefsmigrantsethnicityarticleThabang MasekwamengNo ratings yet

- The "Ethnic" in Indonesia's Communal Conflicts: Violence in Ambon, Poso and SambasDocument3 pagesThe "Ethnic" in Indonesia's Communal Conflicts: Violence in Ambon, Poso and SambasHanifahNo ratings yet

- Malay BruneiDocument20 pagesMalay Bruneisudang johnnyNo ratings yet

- The Khoikhoi 203Document7 pagesThe Khoikhoi 203iyaomolere oloruntobaNo ratings yet

- 5902-Article Text-7829-1-10-20090319 PDFDocument18 pages5902-Article Text-7829-1-10-20090319 PDFReza Maulana HikamNo ratings yet

- 2 CulturalPluralismReinventingAzyumardiDocument10 pages2 CulturalPluralismReinventingAzyumardiIcaios AcehNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Migration On The Development and Spreading of Bantu LanguagesDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Migration On The Development and Spreading of Bantu LanguagesavduongNo ratings yet

- Bbilo Nnopa ProposalDocument18 pagesBbilo Nnopa ProposalMelese LegeseNo ratings yet

- Ndebele Shona Relations Were Cordial PDFDocument2 pagesNdebele Shona Relations Were Cordial PDFNyasha Mutamehama91% (11)

- I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ke Ola I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ka MakeDocument9 pagesI Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ke Ola I Ka 'Ōlelo Nō Ka MakeZen. Ni100% (2)

- History of Philippine Foreign Policy Revised - 075901Document38 pagesHistory of Philippine Foreign Policy Revised - 075901Keiren Faith BaylonNo ratings yet

- HIS203 Complete Note-WPS OfficeDocument8 pagesHIS203 Complete Note-WPS OfficeONAOLAPONo ratings yet

- History of Ethiopia & The Horn Unit 5Document57 pagesHistory of Ethiopia & The Horn Unit 5Suraphel BirhaneNo ratings yet

- Biologi - 5037Document4 pagesBiologi - 5037Ilham Taufik MunandarNo ratings yet

- People's Way of Life Is Commonly Referred To As Culture.Document14 pagesPeople's Way of Life Is Commonly Referred To As Culture.Jhoy Valerie Foy-awonNo ratings yet

- A.Abubakar-muslim Philippines Sulus Muslim Christian Contradictions Mindanao Crisis PDFDocument17 pagesA.Abubakar-muslim Philippines Sulus Muslim Christian Contradictions Mindanao Crisis PDFRina IsabelNo ratings yet

- Hjui 9242Document4 pagesHjui 9242rivandiekaputraNo ratings yet

- Eminov 2000Document37 pagesEminov 2000pycuNo ratings yet

- The Indus VaRley Civilization and Early TibetDocument20 pagesThe Indus VaRley Civilization and Early TibetTenzin SopaNo ratings yet

- Xhosa PeopleDocument7 pagesXhosa PeopleManzini MbongeniNo ratings yet

- The Eastern Nyika: Preliminary Notes On History, Ethnography and LanguageDocument14 pagesThe Eastern Nyika: Preliminary Notes On History, Ethnography and LanguageMartin WalshNo ratings yet

- Henry Assessed Hamattan Corrected ReviewDocument20 pagesHenry Assessed Hamattan Corrected ReviewHenry Gyang MangNo ratings yet

- Apartheid In South Africa - Origins And ImpactFrom EverandApartheid In South Africa - Origins And ImpactRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Full TextDocument30 pagesFull TextbethgovoNo ratings yet

- HANSON The Making of The Maori PDFDocument14 pagesHANSON The Making of The Maori PDFMiguel Aparicio100% (1)

- Buddhaputra and BhumiputraDocument25 pagesBuddhaputra and BhumiputramahamamaNo ratings yet

- Zakaria - Landscapes and Conversions During The Padri WarsDocument40 pagesZakaria - Landscapes and Conversions During The Padri WarsDesi SariNo ratings yet

- Jdhcvda 4099Document17 pagesJdhcvda 4099Shop PeNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Berry's Acculturation FrameworkDocument12 pagesTheorizing Berry's Acculturation FrameworkTrudy DamenNo ratings yet

- Paideusis - Journal For Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Studies Volume 1 1998 ARTICLES (N1ae)Document13 pagesPaideusis - Journal For Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Studies Volume 1 1998 ARTICLES (N1ae)Whodabanger ThebangerNo ratings yet

- The Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDocument44 pagesThe Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDafner Siagian100% (1)

- GST 113 Lecture 1, 2Document14 pagesGST 113 Lecture 1, 2Solomon BinutuNo ratings yet

- Hidden Land of PemakoDocument32 pagesHidden Land of Pemakoneuweil1100% (1)

- The Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicDocument14 pagesThe Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicCarola LalalaNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Ethnicity in Southeast AsiaDocument16 pagesNationalism and Ethnicity in Southeast Asiacrystalgarcia0329No ratings yet

- Historic Aboriginal Pottery at Stono Plantation: A Descriptive Summary by Ronald W. AnthonyDocument13 pagesHistoric Aboriginal Pottery at Stono Plantation: A Descriptive Summary by Ronald W. AnthonySECHSApapersNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Politics, Development and Identity in Peninsular Malaysia: The Orang Asli and The Contest For ResourcesDocument18 pagesIndigenous Politics, Development and Identity in Peninsular Malaysia: The Orang Asli and The Contest For ResourcesThareq Akmal HibatullahNo ratings yet

- Ardes04 - T'boliDocument45 pagesArdes04 - T'boliHANNIE BROQUEZANo ratings yet

- Oromo HistoryDocument4 pagesOromo Historymuzayanmustefa9No ratings yet

- Muller LDancinggoldenstoolsDocument27 pagesMuller LDancinggoldenstoolsudehgideon975No ratings yet

- AJISS 26!3!5 Article 5 Islam As An Ideology of Resistance Mohammed HassenDocument24 pagesAJISS 26!3!5 Article 5 Islam As An Ideology of Resistance Mohammed HassenUsme OnispireNo ratings yet

- Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland ManDocument21 pagesWiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland ManMaria Luísa LucasNo ratings yet

- HANSON - The Making of The MaoriDocument14 pagesHANSON - The Making of The MaoriRodrigo AmaroNo ratings yet

- History Extra PDFDocument13 pagesHistory Extra PDFblenNo ratings yet

- Tomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Document29 pagesTomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Diego MarquesNo ratings yet

- Maori History and ProtestDocument18 pagesMaori History and ProtestHelgeSnorriNo ratings yet

- Makhubo HisvDocument11 pagesMakhubo HisvTHAPELO MAKHUBONo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism in Mindanao, Philippines: The Role of Ethnicity in External and Internal HegemonyDocument20 pagesMulticulturalism in Mindanao, Philippines: The Role of Ethnicity in External and Internal HegemonyAaliyahNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Regionalism in Colonial IndonesiaDocument22 pagesNationalism and Regionalism in Colonial IndonesiaGeoNo ratings yet

- HDR2005 Brown, Graham - Horizontal Inequalities, Ethnic Separatism, and Violent Conflict: The Case of Aceh, IndonesiaDocument11 pagesHDR2005 Brown, Graham - Horizontal Inequalities, Ethnic Separatism, and Violent Conflict: The Case of Aceh, IndonesiaEmma 'Emmachi' AsombaNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Marronage, The Power of Language, and Creole GenesisDocument8 pagesSpiritual Marronage, The Power of Language, and Creole GenesisJason BurrageNo ratings yet

- Maribeth Errb-Catholic and Identity in ManggaraiDocument30 pagesMaribeth Errb-Catholic and Identity in ManggaraiEdward AngimoyNo ratings yet

- Education, Recognition, and The Sami People of NorwayDocument19 pagesEducation, Recognition, and The Sami People of NorwayJonas JakobsenNo ratings yet

- The 7th Meeting AssignmentDocument1 pageThe 7th Meeting AssignmentfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelDocument9 pagesThe Dynamics of Muslim and Christian RelfarhanNo ratings yet

- TASKDocument7 pagesTASKfarhanNo ratings yet

- The Second GroupDocument18 pagesThe Second GroupfarhanNo ratings yet

- Blossoms of The Savannah Kcse Essay Questions and AnswersDocument32 pagesBlossoms of The Savannah Kcse Essay Questions and AnswersMichael Mike100% (1)

- SelfEmploymentBook PDFDocument198 pagesSelfEmploymentBook PDFexecutive engineerNo ratings yet

- GS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormDocument2 pagesGS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormJP De La PeñaNo ratings yet

- Using Self-Reliance As A Ministering Tool (Revised June 13, 2018)Document18 pagesUsing Self-Reliance As A Ministering Tool (Revised June 13, 2018)joseph malawigNo ratings yet

- English For Practical UseDocument4 pagesEnglish For Practical Usenursaida100% (1)

- Financial Status AffectingDocument9 pagesFinancial Status AffectingChen ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- BFN Amphitheater Lineup 2023Document2 pagesBFN Amphitheater Lineup 2023TMJ4 NewsNo ratings yet

- English QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesEnglish QuestionnairePamelaCindyTumuyu80% (15)

- CIV PRO DigestDocument54 pagesCIV PRO DigestbcarNo ratings yet

- DH 2011 1008 Part A DCHB KishanganjDocument594 pagesDH 2011 1008 Part A DCHB Kishanganjaditi kaviwalaNo ratings yet

- Arts in Muslim SouthDocument12 pagesArts in Muslim SouthKem Paulo QueNo ratings yet

- 27.0 - Confined Spaces v3.0 EnglishDocument14 pages27.0 - Confined Spaces v3.0 Englishwaheed0% (1)

- Corpuz vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesCorpuz vs. PeopleAli NamlaNo ratings yet

- Errors About Detective StoriesDocument3 pagesErrors About Detective StoriesAgustin IssidoroNo ratings yet

- AIFs in GIFT IFSC Booklet October 2020Document12 pagesAIFs in GIFT IFSC Booklet October 2020Karthick JayNo ratings yet

- Economy - Indian EconomicsDocument382 pagesEconomy - Indian EconomicshevenpapiyaNo ratings yet

- Presentation To IEEDocument17 pagesPresentation To IEEomairakhtar12345No ratings yet

- Philippine School of Business Administration R. Papa ST., Sampaloc, ManilaDocument12 pagesPhilippine School of Business Administration R. Papa ST., Sampaloc, ManilaNaiomi NicasioNo ratings yet

- Publishing and Disseminating Dalit Literature: Joshil K. AbrahamDocument8 pagesPublishing and Disseminating Dalit Literature: Joshil K. AbrahamkalyaneeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Quiz 1Document3 pagesChapter 4 Quiz 1yash_28No ratings yet

- Quarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberDocument1 pageQuarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberJenny Lyn MasgongNo ratings yet

- History of PlumbingDocument2 pagesHistory of PlumbingPaola Marie JuanilloNo ratings yet

- Compound Complex SentenceDocument32 pagesCompound Complex SentenceReynaldo SihiteNo ratings yet

- Annual Implementation Plan: Calendar Year 2021Document5 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan: Calendar Year 2021Guia Marie Diaz BriginoNo ratings yet

- 78903567-Garga by GargacharyaDocument55 pages78903567-Garga by GargacharyaGirish BegoorNo ratings yet

- The Thin Red Line: European Philosophy and The American Soldier at WarDocument8 pagesThe Thin Red Line: European Philosophy and The American Soldier at Warnummer2No ratings yet

- Case Digest - Carpio VS Sulu Resources Development CorporationDocument3 pagesCase Digest - Carpio VS Sulu Resources Development Corporationfred rhyan llausasNo ratings yet