Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 Famous Paintings

10 Famous Paintings

Uploaded by

John Rey Logrosa0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views12 pages1. Vincent van Gogh's The Starry Night, painted in 1889 at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, reflects his turbulent state of mind through swirling brushstrokes depicting the night sky.

2. Johannes Vermeer's 1665 painting Girl with a Pearl Earring portrays an unknown sitter looking over her shoulder intimately at the viewer, though some speculate it was his maid.

3. Gustav Klimt's 1907-1908 painting The Kiss depicts intimate figures as luxurious symbols of the era through gold leaf and patterns inspired by Byzantine art.

Original Description:

Original Title

10 Famous Paintings.pptx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. Vincent van Gogh's The Starry Night, painted in 1889 at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, reflects his turbulent state of mind through swirling brushstrokes depicting the night sky.

2. Johannes Vermeer's 1665 painting Girl with a Pearl Earring portrays an unknown sitter looking over her shoulder intimately at the viewer, though some speculate it was his maid.

3. Gustav Klimt's 1907-1908 painting The Kiss depicts intimate figures as luxurious symbols of the era through gold leaf and patterns inspired by Byzantine art.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views12 pages10 Famous Paintings

10 Famous Paintings

Uploaded by

John Rey Logrosa1. Vincent van Gogh's The Starry Night, painted in 1889 at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, reflects his turbulent state of mind through swirling brushstrokes depicting the night sky.

2. Johannes Vermeer's 1665 painting Girl with a Pearl Earring portrays an unknown sitter looking over her shoulder intimately at the viewer, though some speculate it was his maid.

3. Gustav Klimt's 1907-1908 painting The Kiss depicts intimate figures as luxurious symbols of the era through gold leaf and patterns inspired by Byzantine art.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 12

2.

Vincent van Gogh,

The Starry Night, 1889

Vincent Van Gogh’s most popular painting,

The Starry Night was created by Van Gogh

at the asylum in Saint Remy, where he’d

committed himself in 1889. Indeed, The

Starry Night seems to reflect his turbulent

state of mind at the time, as the night sky

comes alive with swirls and orbs of

frenetically applied brush marks springing

from the yin and yang of his personal

demons and awe of nature.

3. Johannes Vermeer,

Girl with a Pearl Earring,

1665

Johhanes Vermeer’s 1665 study os a young

woman is startlingly real and startlingly

modern, almost as if it were a photograph.

This gets into the debate over whether or

not Vermeer employed a pre-photographic

device called a camera obscura to create

the image. Leaving that aside, the sitter is

unknown, though it’s been speculated that

she might have been Vermeer’s maid. He

portrays her looking over her shoulder,

locking her eyes with the viewers as if

attempting to establish an intimate

connection across the centuries. Technically

speaking, Girl isn’t a portrait, but rather an

example of the Dutch genre called a tronie-

a headshot meant more as still life of facial

features than as an attempt to capture a

likeness.

4. Gustav Klimt, The

Kiss, 1907-1908

Opulently gilded and extravagantly

patterned, The Kiss, Gustav Klimt’s fin de-

siècle portrayal of intimacy, is a mix of

Symbolism and Vienna Jugendstil, the

Austrian variant of Art Nouveau. Klimt

depicts his subjects as mythical figures

made modern by luxuriant surfaces of up-

to-the moment graphic motifs. The work is a

highpoint of the artist’s Golden Phase

between 1899 and 1910 when he often

used gold leaf – a technique inspired by a

1903 trip to the Basilica di San Vitale in

Ravenna, Italy, where he saw the church’s

famed Byzantine mosaics.

5. Sandro Botticelli, The

Birth of Venus. 1484-

1486

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus was the first full-

length, non-religious nude since antiquity, and

was made for Lorenzo de Medici. It’s claimed

that the figure of the Goddess of Love is

modeled after one Simonetta Cattaneo

Vespucci, whose favors were allegedly shared by

Lorenzo and his younger brother, Giuliano.

Venus is seen being blown ashore on a giant

clamshell by the wind gods Zephyrus and Aura

as the personification of spring awaits on land

with a cloak. Unsurprisingly, Venus attracted the

ire of Savonarola, the Dominican monk who led

a fundamentalist crackdown on the secular

tastes of the Florentines.

6. James Abbott McNeill

Whistler, Arrangement in

Grey and Black No. 1,

1871

Whisler’s Mother, or Arrangement in Grey

and Black no. 1, as it’s actually titled,

speaks to the artist’s ambition to pursue art

for art’s sake. James Abbott McNeill

Whistler painted the work in his London

studio in 1871, and in it, the formality of

portraiture becomes an essay form.

Whistler’s mother Anna is pictured as one of

several elements locked into an

arrangement of right angles. Her severe

expression fits in with the rigidity of the

composition, and it is somewhat ironic to

note that despite Whistler’s formalist

intentions, the painting became a symbol of

motherhood.

7. Jan van Eyck, The

Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

One of the most significant works produced

during the Northern Renaissance, this

composition is believed to be one of the first

paintings executed in oils. A full-length

double portrait, it reputedly portrays an

Italian merchant and a woman who may or

may not be his bride. In 1934, the

celebrated art historian Erwin Panofsky

proposed that the painting is actually a

wedding contract. What can be reliably said

is that the piece is one of the fist depictions

of an interior using orthogonal perspective

to create a sense of space that seems

contiguous with the viewer’s own; it feels

like a painting you could step into.

8. Hieronymus Bosch,

The Garden of Earthly

Delights, 1503-1515

This fantastical triptych is generally

considered a distant forerunner to

Surrealism. In truth, it is the expression of a

late medieval artist who believed that God

and the Devil, Heaven and Hell were real.

Of the three scenes depicted, the left panel

shows Christ presenting Eve to Adam, while

the right one features the depredations of

Hell; less clear is whether the center panel

depicts Heaven. In Bosch’s perfervid vision

of Hell, an enormous set of ears wielding a

phallic knife attacks the damned, while a

bird-beaked bug king with a chamber pot for

a crown sits on its throne, devouring the

doomed promptly defecating them out

again. This riot of symbolism has been

largely impervious to interpretation, which

may account for its widespread appeal.

9. Geroges Seurat, A

Sunday Afternoon on

the Island of La Grande

Jatte, 1884-1886

Georges Seurat’s masterpiece, evoking the

Paris of La Belle Epoque, is actually

depicting a working-class suburban scene

well outside the city’s center. Seurat often

made this milieu his subject, which differed

from the bourgeois portrayals of his

Impressionist contemporaries. Seurat

abjured the capture-the-moment approach

of Manet, Monet, and Degas, going instead

for the sense of timeless permanence found

in Greek sculpture. And that is exactly what

you get in this frieze-like processional of

figures whose stillness is in keeping with

Seurat’s aim to creating a classical

landscape in modern form.

10. Pablo Picasso, Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon,

1907

The ur-canvas of 20th-century art, Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon ushered in the

modern era by decisively breaking with the

representational tradition of Western

painting, incorporating allusions to the

African masks that Picasso had seen in

Paris’s ethnographic DNA also includes El

Greco’s The Vision of Saint John (1608-14),

now hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of

Art. The women being depicted are actually

prostitutes in a brothel in the artist’s native

Barcelona.

THE END

BY: DEBERLITA P. ESTORGIO BSED ENGLISH I-C

You might also like

- Gombrich, Ernst, H - MacGregor, Neil - Penny, Nicholas - Shadows. The Depiction of Cast Shadows in Western Art. Reprint (2014)Document102 pagesGombrich, Ernst, H - MacGregor, Neil - Penny, Nicholas - Shadows. The Depiction of Cast Shadows in Western Art. Reprint (2014)skiniks100% (1)

- Art and The Human FacultiesDocument9 pagesArt and The Human FacultiesRyuen ChouNo ratings yet

- Youens, Excavating An Allegory Pierrot Lunaire Texts (JASI 8-2, 1984)Document11 pagesYouens, Excavating An Allegory Pierrot Lunaire Texts (JASI 8-2, 1984)Victoria Chang100% (1)

- As 1900 050 97 TB enDocument48 pagesAs 1900 050 97 TB enYZ Cem Soydemir100% (1)

- PDF GenfinalDocument29 pagesPDF GenfinalLorenzoNo ratings yet

- Healthymagination at Ge Healthcare SystemsDocument5 pagesHealthymagination at Ge Healthcare SystemsPrashant Pratap Singh100% (1)

- PHD Progress Presentation TemplateDocument11 pagesPHD Progress Presentation TemplateAisha QamarNo ratings yet

- Category: Grading Rubric For Storyboard ProjectDocument1 pageCategory: Grading Rubric For Storyboard ProjectRyan EstonioNo ratings yet

- Newyorkarttop Famous Paintings in Art History RankedDocument2 pagesNewyorkarttop Famous Paintings in Art History Rankedgoocsherlyn18No ratings yet

- GEC 6 ART APPRECIATION Famous ArtDocument40 pagesGEC 6 ART APPRECIATION Famous ArtNovie LabadorNo ratings yet

- PAINTERSDocument9 pagesPAINTERSMary Jane MalabananNo ratings yet

- PaintingsDocument55 pagesPaintingsSahNo ratings yet

- The Most Famous PaintingsDocument3 pagesThe Most Famous PaintingssuluNo ratings yet

- All About Sandro BotticelliDocument5 pagesAll About Sandro Botticellilxikxaxxin ImonéNo ratings yet

- The Meaning Behind The PaintingDocument4 pagesThe Meaning Behind The PaintingZanila YoshiokaNo ratings yet

- GEARTAP RecitationDocument4 pagesGEARTAP RecitationAllysa Sarmiento HonraNo ratings yet

- Subject and Ways of Art (Alyza Caculitan)Document15 pagesSubject and Ways of Art (Alyza Caculitan)Alyza CaculitanNo ratings yet

- ADocument6 pagesADjura JovanovicNo ratings yet

- The Birth of Venus (Botticelli) : InterpretationsDocument4 pagesThe Birth of Venus (Botticelli) : InterpretationsBogdan CurtaNo ratings yet

- Sandro Bottecelli's: "The Birth of Venus"Document21 pagesSandro Bottecelli's: "The Birth of Venus"Nanditha PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Hum 101Document4 pagesHum 101Aki Love HillNo ratings yet

- Classical Studies 3.5 2017Document9 pagesClassical Studies 3.5 2017Ronan CarrollNo ratings yet

- Top50MostFamousPaintings PDFDocument50 pagesTop50MostFamousPaintings PDFwin buf100% (1)

- 07 Nude AwakeningDocument4 pages07 Nude AwakeningdelfinovsanNo ratings yet

- Van Goghs AgonyDocument13 pagesVan Goghs AgonygahgahgahNo ratings yet

- Most Notable Artist in HistoryDocument10 pagesMost Notable Artist in HistorystarzaldejaNo ratings yet

- From Goya To ErnstDocument7 pagesFrom Goya To ErnstN BNo ratings yet

- Pallas and The Centaur and The Primavera. This DebateDocument2 pagesPallas and The Centaur and The Primavera. This DebateKebab TvrtkićNo ratings yet

- Exhibition Catalogue ReviewDocument4 pagesExhibition Catalogue Reviewraul0benitoNo ratings yet

- GoddessesDocument2 pagesGoddessesJohn JamesNo ratings yet

- BAROQUEDocument4 pagesBAROQUEWin Yee Mon ThantNo ratings yet

- The Cosmonaut of The Erotic FutureDocument9 pagesThe Cosmonaut of The Erotic FutureGianna Marie AyoraNo ratings yet

- ArtenglishDocument11 pagesArtenglishРуня ГрушаNo ratings yet

- Wimsey the Bloodhound's Institute of Houndish Art Volume OneFrom EverandWimsey the Bloodhound's Institute of Houndish Art Volume OneNo ratings yet

- Renaissance ArtDocument6 pagesRenaissance ArtleeknoowieeNo ratings yet

- ART 100 The Genre of The NudeDocument19 pagesART 100 The Genre of The Nudenyeshim20No ratings yet

- BDocument7 pagesBDjura JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Gray-The Vision SceneDocument11 pagesGray-The Vision Scenealloni1No ratings yet

- Chapter6 PromoDocument24 pagesChapter6 Promoapi-274677147No ratings yet

- Ancient Aliens Based On HistoryDocument28 pagesAncient Aliens Based On HistoryGino ToralbaNo ratings yet

- ContemporaryDocument2 pagesContemporarySasay DiamanteNo ratings yet

- Project in Humanities: Mrs. Anita Boral A-45Document6 pagesProject in Humanities: Mrs. Anita Boral A-45Randy Gerard SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Vision After The SermonDocument9 pagesVision After The SermonPatrick AlimuinNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The NewsDocument3 pagesWelcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The Newssagerel276No ratings yet

- Charles Baudelaire - The Modern Public and PhotographyDocument6 pagesCharles Baudelaire - The Modern Public and PhotographyCarlos Henrique SiqueiraNo ratings yet

- An Intimate Poetry of Pain and Laughter: ExhibitsDocument3 pagesAn Intimate Poetry of Pain and Laughter: ExhibitsCarlos RoderoNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Romanticism, Realism, and Expressionism in ArtDocument5 pagesA Guide To Romanticism, Realism, and Expressionism in ArtRowena Odhen UranzaNo ratings yet

- Robert Rosenblum - The Origin of Painting A Problem in The Iconography of Romantic ClassicismDocument17 pagesRobert Rosenblum - The Origin of Painting A Problem in The Iconography of Romantic Classicismlaura mercaderNo ratings yet

- James EnsorDocument2 pagesJames EnsorJuan José BurziNo ratings yet

- Pablo Picasso (25 October 1881 - 8 April 1973)Document35 pagesPablo Picasso (25 October 1881 - 8 April 1973)Shafaq NazirNo ratings yet

- On The Iconography of The Nymph of The Fountain by Lucas Cranach The ElderDocument6 pagesOn The Iconography of The Nymph of The Fountain by Lucas Cranach The ElderMárcio MendesNo ratings yet

- The Last History Painter - William Adolphe Bouguereau - The Imaginative ConservativeDocument4 pagesThe Last History Painter - William Adolphe Bouguereau - The Imaginative ConservativeNadge Frank AugustinNo ratings yet

- OdalisqueDocument3 pagesOdalisqueEdward John AglehamNo ratings yet

- Vênus de MiloDocument10 pagesVênus de MiloLenineNo ratings yet

- THE Legend Literature: Devil-CompactDocument19 pagesTHE Legend Literature: Devil-CompactsupriyatnoyudiNo ratings yet

- Portrait - WikipediaDocument30 pagesPortrait - Wikipediakhloodwalied304No ratings yet

- Jan MielDocument6 pagesJan MielBenjamin KonjicijaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Appreciating A Collaborative Work (P. 9)Document2 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Appreciating A Collaborative Work (P. 9)Chris Gabriel UcolNo ratings yet

- Pas001,+1762 6621 1 CEDocument12 pagesPas001,+1762 6621 1 CEMarius StanNo ratings yet

- W.B.yeats Leda and The Swan 2Document5 pagesW.B.yeats Leda and The Swan 2Daineanu Madalina Delia100% (1)

- New English File - Elementary File 10 - Test 10Document5 pagesNew English File - Elementary File 10 - Test 10Sanja IlovaNo ratings yet

- S Bing 0605175 Chapter4Document29 pagesS Bing 0605175 Chapter4Rose GreenNo ratings yet

- Underwood C. P., "HVAC Control Systems, Modelling Analysis and Design" RoutledgeDocument2 pagesUnderwood C. P., "HVAC Control Systems, Modelling Analysis and Design" Routledgeatif shaikhNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIIDocument3 pagesChapter IIIRenan S. GuerreroNo ratings yet

- 723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardDocument40 pages723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardMichael TanNo ratings yet

- Aztec MagicDocument2 pagesAztec MagicBob MarinoNo ratings yet

- Glutamine USPDocument3 pagesGlutamine USPJai MurugeshNo ratings yet

- Horn Persistence Natural HornDocument4 pagesHorn Persistence Natural Hornapi-478106051No ratings yet

- Science Cubing GettingNerdyLLCDocument3 pagesScience Cubing GettingNerdyLLCVanessa PassarelloNo ratings yet

- College of Engineering Course Syllabus Information Technology ProgramDocument5 pagesCollege of Engineering Course Syllabus Information Technology ProgramKhaled Al WahhabiNo ratings yet

- Effect of IBA and NAA With or Without GA Treatment On Rooting Attributes of Hard Wood Stem Cuttings of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.)Document5 pagesEffect of IBA and NAA With or Without GA Treatment On Rooting Attributes of Hard Wood Stem Cuttings of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.)warlord_ckNo ratings yet

- Keraplast Wound Care BrochureDocument4 pagesKeraplast Wound Care BrochureclventuriniNo ratings yet

- Division) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 FiledDocument16 pagesDivision) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 Filedsoojung jungNo ratings yet

- Research in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagDocument17 pagesResearch in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagBobby DNo ratings yet

- Empower 2e B1+ Word List GermanDocument94 pagesEmpower 2e B1+ Word List GermanwaiNo ratings yet

- Crossing The Threshold - Audrey TopazianDocument3 pagesCrossing The Threshold - Audrey Topazianapi-502833469No ratings yet

- Roll Number Name Subject Marks Obtained Total Grade Result: 2967917 Bhagesh Ari MauryaDocument3 pagesRoll Number Name Subject Marks Obtained Total Grade Result: 2967917 Bhagesh Ari MauryaShiv PoojanNo ratings yet

- How To Use ExscannerDocument51 pagesHow To Use ExscannerRenee Rose TropicalesNo ratings yet

- Cavite Mutiny AccountsDocument4 pagesCavite Mutiny AccountsSAMANTHA ANN GUINTONo ratings yet

- TM I RubenDocument165 pagesTM I RubenMark Kevin DaitolNo ratings yet

- In Re SantiagoDocument2 pagesIn Re SantiagoKing BadongNo ratings yet

- Self WorthDocument5 pagesSelf WorthSav chan123No ratings yet

- Indian Feminism - Class, Gendera & Identity in Medieval AgesDocument33 pagesIndian Feminism - Class, Gendera & Identity in Medieval AgesSougata PurkayasthaNo ratings yet

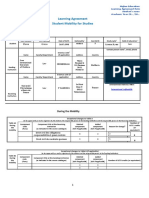

- Learning Agreement During The MobilityDocument3 pagesLearning Agreement During The MobilityVictoria GrosuNo ratings yet

- Dan Webb Concealment GradeDocument2 pagesDan Webb Concealment Gradeapi-565691734No ratings yet

- CHN Transes Week 1Document5 pagesCHN Transes Week 1cheskalyka.asiloNo ratings yet