Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wister7e PPT Chapter5

Wister7e PPT Chapter5

Uploaded by

Justine May0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views33 pagesThis document discusses theories and research used to understand aging phenomena. It begins by explaining that theories provide explanations for observations and help answer "why" questions, while research helps develop and test theories. It then outlines several foundational perspectives - structural functionalism, interpretive, and conflict - before detailing contemporary perspectives like social exchange theory, postmodernism, feminism, life course, activity theory, disengagement theory, and continuity theory. It emphasizes that multiple perspectives are needed to fully understand aging.

Original Description:

Original Title

Wister7e_PPT_Chapter5

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses theories and research used to understand aging phenomena. It begins by explaining that theories provide explanations for observations and help answer "why" questions, while research helps develop and test theories. It then outlines several foundational perspectives - structural functionalism, interpretive, and conflict - before detailing contemporary perspectives like social exchange theory, postmodernism, feminism, life course, activity theory, disengagement theory, and continuity theory. It emphasizes that multiple perspectives are needed to fully understand aging.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views33 pagesWister7e PPT Chapter5

Wister7e PPT Chapter5

Uploaded by

Justine MayThis document discusses theories and research used to understand aging phenomena. It begins by explaining that theories provide explanations for observations and help answer "why" questions, while research helps develop and test theories. It then outlines several foundational perspectives - structural functionalism, interpretive, and conflict - before detailing contemporary perspectives like social exchange theory, postmodernism, feminism, life course, activity theory, disengagement theory, and continuity theory. It emphasizes that multiple perspectives are needed to fully understand aging.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 33

5

Theories and Research

in Explaining and

Understanding Aging

Phenomena

Introduction: Seeking Knowledge

and Understanding

• We often read information (e.g., facts, patterns,

observations about individual and population aging)

in journals, books, government reports, and mass

media.

• Yet “description” represents only one level of

understanding—we also need to know why a fact or

observation exists (e.g., why women are the primary

caregivers for the elderly).

• To better understand, explain, interpret phenomena,

theories (theoretical perspectives) and research methods

are employed.

The Goals of Scholarly Research

• Theory: a set of ideas that explains of an empirical

finding or observation. Specifically, a theory:

• provides a set of propositions to model how social or

physical world operates;

• helps answers the “why” and “how” questions;

• stimulates the development and accumulation of

knowledge;

• facilitates interventions through development,

implementation, and evaluation of policies, services, and

programs.

Developing Knowledge: Multiplicity

in Perspectives and Theories

• Just as different research methods—quantitative and

qualitative methods—are needed to answer

questions, different theories (theoretical

perspectives) are necessary for increasing our

knowledge.

• Each theory is based on different assumptions and

employs different concepts.

• “Foundational” perspectives (structural

functionalist, interpretive, and conflict perspectives)

provide a general orientation to developing research

questions in social research.

Foundational Perspectives

• “Foundational” perspectives provide a general

orientation to developing research questions in

social research.

• Structural functionalist perspective

• Interpretive perspective

• Conflict perspective

The Structural Functionalist

Perspective

• Focuses on relationships between social structures/

institutions (including norms, roles, and

socialization) and the individual.

• Social structure/institutions (like organs in the

human body) function together to regulate

behaviour so society runs smoothly.

• e.g., mandatory retirement removes older individuals

from the social role of “worker.” This is “functional” to

society because it enables younger people to enter labour

force. Older worker adjusts to role of “retiree” and is

rewarded accordingly (with pension income).

The Social Constructionist/

Interpretive Perspective

• The individual defines—through verbal or symbolic

interaction with others (e.g., verbal language, type

of clothing)—a social situation in terms of what the

situation means to him or her.

• e.g., a university student may present (in terms of

language, mannerisms, clothing) him or her “self”

differently to others during class as opposed to at a job

interview or at home with parents.

• It is a form of micro-level analysis, and does not

consider the larger social system in which the

specific individual is found.

The Conflict Perspective

• Society is comprised of competing/conflicting

groups, and is dynamic and changing.

• If one group has more power and money, others believe

that they are exploited and so strive to obtain some or all

of the resources from those in control—social interaction

involves negotiation to resolve conflict.

• e.g., conflict between young people (who have yet to gain

power) and middle-aged people (who have most power), or

between older people (who lost their power and authority) and

middle-aged/younger people.

Contemporary Perspectives on

Aging

• Several theoretical perspectives, based on the

foundational perspectives, have been developed

more recently to explain aging and age-related

processes.

• Social exchange perspective

• Postmodern perspective

• Feminist perspective

• Life-course perspective

Contemporary Perspectives on

Aging, cont’d

• Other age-specific theories include:

• Activity theory

• Disengagement theory

• Continuity theory

• Age stratification

• Political economy of aging

• Critical gerontology

The Social Exchange Perspective

• Individuals search for social situations in which

valued outcomes are possible and in which their

social, emotional, and psychological needs can be

met.

• Social scientists seek knowledge about past

experiences and current personal needs, values, and

options before they determine the amount of

equality or inequality in a specific social exchange

relationship.

• Unbalanced exchanges may also lead to problems (e.g.,

abuse).

The Postmodern Perspective

• Postmodernism argues that science and knowledge

are inexorably linked to social control and power.

• Postmodernists employ two basic intellectual

approaches: social construction and deconstruction.

1. Social constructionism: reality is socially constructed

and evolves as we actively interact with others or

record our thoughts and meanings

2. Deconstructionism: language is a social concept that

must be deconstructed for us to understand and explain

the “real” meaning of thoughts and behaviour

The Feminist Perspective

and Masculinity Theory

• Gender is an organizing principle for studying

social life across the life course, and it can create

inequities that advantage men and disadvantage

women, especially in the later years.

• The goals of feminist research are to understand

social reality through the eyes and experiences of

women, to eliminate gender-based oppression and

inequality, and to improve the lives of women.

• Gender inequities across the life course are socially

constructed, institutionalized, and perpetuated by

dynamic social, economic, and political forces

rather than by individual choices.

The Life-Course Perspective: A

Dynamic Bridging Approach

• The life-course perspective provides an analytical

framework for understanding the interplay between

individual lives and changing social structures, and

between personal biography and societal history.

• Our life course is composed of multiple,

interdependent trajectories relating to education,

work, family, and leisure. What happens along one

trajectory often has an effect on other trajectories.

Activity (Substitution) Theory

• Individual adaptation in later life involved

continuing an active life.

• Continued social interaction would maintain the

self-concept and, hence, a sense of well-being or

life satisfaction.

• Two basic hypotheses stem from this theory:

1. High activity and maintenance of roles is positively

related to a favourable self-concept

2. A favourable self-concept is positively related to life

satisfaction—that is, experiencing adjustment,

successful aging, well-being, and high morale

Disengagement Theory

• Only through a process of work-role withdrawal by

older people can young people enter the labour force.

• Thus, for the mutual benefit of individuals and

society, aging should involve a voluntary process by

which older people disengage from society and

society disengages from the individual.

• The process of disengagement results in less

interaction between an individual and others in

society and is assumed to be a universal process.

• Critics argue that the process was not universal, voluntary,

or satisfying and that not everyone disengages from their

previously established role set.

Continuity Theory

• As people age, they strive to maintain continuity in

their lifestyle.

• People adapt more easily to aging if they maintain a

lifestyle similar to that developed in the early and middle

years.

• In reality, aging involves both continuity and

change.

Age Stratification: The Aging and

Society Paradigm

• Society is segregated by age into:

1. Childhood and adolescence for education

2. Young and middle adulthood for work

3. The later years for retirement and leisure

• Through a process of role allocation or age grading,

individuals gain access to social roles on the basis

of chronological, legal, or social age.

• Through a process of role allocation or age grading,

individuals gain access to social roles on the basis

of chronological, legal, or social age.

The Political Economy of Aging

• Politics and economics, not demography, determine

how old age is constructed and valued in a society.

• The onset of dependency and diminished socio-

economic status and self-esteem in the later years

are an outcome not of biological deterioration but of

public policies, economic trends, and changing

social structures.

Critical Gerontology

• Critical gerontology is “a collection of questions,

problems and analyses that have been excluded by

established (mainstream) gerontologists.” (Baars et

al.)

• Critical gerontology consists of two paths:

1. The political economy of aging

2. A more humanistic path based on the deconstruction of

meanings in communication

• Critical gerontology has generated knowledge of

what it means to grow old within specific class,

gender, racial, and ethnic boundaries, as well as how

to empower older people to improve their lives.

Intersectionality Theory

• Privilege and disadvantage needs to be examined at

the intersections of major systems of inequality

embedded in society along age, gender, sexuality,

social class, race, and ethnicity lines.

The Link between Theory and

Research

• In addition to theories/perspectives, research is

needed to discover, describe, and interpret facts,

behaviour, and patterns we observe in the social

world.

• Research is needed to both develop new theories

and test present ones.

• Research helps to:

• refute or support hypotheses or theories;

• initiate revision of existing theories or perspectives;

• construct new theories or perspectives.

The Selection of

Research Methods

• After a research question is framed using a

theoretical perspective, a method is chosen to

answer the question.

• Generally speaking, there are two research methods

1. qualitative—based on open-ended interviews to

interpret the meaning of what people say, do, or think;

2. quantitative—based on surveys or analyses of existing

data to reach conclusions statistically.

The Selection of

Research Methods, cont’d

• Combination of both research methods—multi-

method or mixed-methods—can also be used to

draw upon synergies of various types of information

to obtain more complete picture.

• e.g., qualitative methods for understanding aging

phenomenon at the individual level and quantitative

methods for understanding at the societal level.

The Selection of

Research Methods, cont’d

• Common qualitative and quantitative research

methods used to study aging include:

• Secondary analysis

• Historical and literary methods

• Narrative gerontology

• Survey research

• Participant observation

• Evaluation and intervention research

• Participatory action research

• Cross-national research

Issues in Quantitative Research

Designs

• A major concern when conducting quantitative-

based aging research is discerning whether findings

are due to age effects (most often, age effects are the

intended goal of research), cohort effects, or period

effects.

• Age effects are differences attributed to biological,

psychological, and social aging processes of the

individual.

• Cohort effects are socio-economic and cultural

experiences shared by all individuals born around the

same time.

• Period effects are the historical and societal events that

affect all individuals in the population, regardless or age

Issues in Quantitative Research

Designs, cont’d

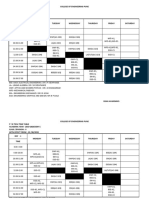

• Cross-sectional research, such as survey research,

involves recording observations of individuals at

different ages at one point in time and reporting the

results for each age group.

• For example, the results of a cross-sectional study on the

relationship between age and obesity, as shown in Table

5.1.

• While these results suggest obesity levels rise with age, we

cannot conclude that the differences are due to growing old—

that is, to an aging effect. They do not allow us to disentangle

age, cohort, or period effects.

Issues in Quantitative Research

Designs, cont’d

• Longitudinal research involves collecting (e.g., with

a survey) data over time, including samples of

different people (a trend design) or the same people

at different points in time (a panel design).

• A panel longitudinal design provides more accurate

explanations of the aging process because the same

individuals are studied over time, and the information

can be used to identify and explain patterns associated

with aging—they allow us to disentangle age and cohort

effects.

Issues in Quantitative Research

Designs, cont’d

• Cohort analysis was developed in response to the

limitations of cross-sectional and panel longitudinal

designs for studying aging processes across time.

• Cohort analysis uses a number of sequential cross-

sectional data sets with the same variables (e.g., health

survey data for 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) to

help identify age changes, cohort differences, and period

effects.

Issues in Quantitative Research

Designs, cont’d

• Another concern when doing quantitative-based

aging research is representation of the sample data.

• Some groups are difficult to sample, such as those who

are frail or those living in long-term care, yet they

constitute an important and growing segment of the older

population.

• Using a “proxy” (e.g., a caregiver or family member) on behalf

of the older subject can help to improve representation and data

quality.

Issues in Qualitative

Research Designs

• Qualitative studies tend to be based on non-random

(e.g., “convenient”) samples, and thus are less

generalizable to the larger population than

quantitative studies.

• Qualitative researchers must also avoid having their

preconceptions interfere with gathering and

interpreting data.

Summary

• Theories/perspectives help explain and interpret

data and observations about aging processes.

• The “foundational” perspectives of structural

functionalism, interpretism, and conflictism,

underlie many of the contemporary perspectives on

social aging.

• Two primary methods of data collection are

qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Summary, cont’d

• No single theoretical perspective or methodological

approach dominates aging research—some theories

(and research methods) are used primarily to study

micro-level (individual) aging questions; others are

used for macro-level questions (issues at the level of

society or the population).

You might also like

- Imagining Ai How The World Sees Intelligent Machines Stephen Cave Full ChapterDocument67 pagesImagining Ai How The World Sees Intelligent Machines Stephen Cave Full Chapterada.marquez749100% (11)

- Chapter 4 Socialization and The Life CourseDocument41 pagesChapter 4 Socialization and The Life CourseWaqas RehmanNo ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN IN SCIENCE 8 (1st Discussion)Document7 pagesLESSON PLAN IN SCIENCE 8 (1st Discussion)John Mark Laurio100% (8)

- Case Study Report Format GuidelineDocument10 pagesCase Study Report Format GuidelineJoanne FerrerNo ratings yet

- Gender and SocietyDocument37 pagesGender and SocietyJosef PlenoNo ratings yet

- The Study of SociologyDocument24 pagesThe Study of SociologyMira Lei MarigmenNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Sociology: The Study of Social Behavior and The Organization of Human SocietyDocument32 pagesIntroduction To Sociology: The Study of Social Behavior and The Organization of Human SocietyFlexNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Social Structure and Social InteractionDocument33 pagesChapter 5 Social Structure and Social InteractionWaqas RehmanNo ratings yet

- Filipino Personality and Social WorkDocument55 pagesFilipino Personality and Social WorkRomy VelascoNo ratings yet

- Perspective On Aging IV: Social Psychological Aspects of AgingDocument67 pagesPerspective On Aging IV: Social Psychological Aspects of Agingnilton31No ratings yet

- Society Is Who: People Shape Lives Aggregated Patterned Ways Distinguish OtherDocument24 pagesSociety Is Who: People Shape Lives Aggregated Patterned Ways Distinguish OtherRhett SageNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 of 09th Aug 2022 SlidesDocument64 pagesLecture 2 of 09th Aug 2022 SlidesHari JNo ratings yet

- Sat EstDocument9 pagesSat EstRegina IlustreNo ratings yet

- What Are Your Likes and Dislikes?Document38 pagesWhat Are Your Likes and Dislikes?Creampop DashNo ratings yet

- Peers Family School Mass Media Religion Workplace StateDocument38 pagesPeers Family School Mass Media Religion Workplace StateTonette 'dgreat Lautrizo MagcamitNo ratings yet

- Sociological PerspectiveDocument41 pagesSociological PerspectiveLeslie Ann Cabasi Tenio100% (1)

- Sociology: Sociological Theory 1 Lecture HoursDocument19 pagesSociology: Sociological Theory 1 Lecture HoursMemes WorldNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Inst 1Document8 pagesModule 3 Inst 1Denny Hannah QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Soci 1000 Test ReviewDocument4 pagesSoci 1000 Test ReviewjeffNo ratings yet

- Chapter#4 SocilizationDocument17 pagesChapter#4 SocilizationasasasNo ratings yet

- Sociology Unit 1 - Lesson 6 - Fundamental ConceptsDocument32 pagesSociology Unit 1 - Lesson 6 - Fundamental ConceptsmikayylacNo ratings yet

- Final SocDocument6 pagesFinal SoczeinabNo ratings yet

- Gender and Sexuality As A Subject of InquiryDocument14 pagesGender and Sexuality As A Subject of InquiryHesed Peñera100% (7)

- Soc114 ch01 2022Document21 pagesSoc114 ch01 2022Thanh TrúccNo ratings yet

- Week 3Document22 pagesWeek 3Stephanie Gayle RuizNo ratings yet

- Sociology Lecture Four On SocializationDocument22 pagesSociology Lecture Four On Socializationharis maqsoodNo ratings yet

- SociologyDocument21 pagesSociologyAnkit TiwariNo ratings yet

- DISS - Lesson 5 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas in Social SciencesDocument33 pagesDISS - Lesson 5 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas in Social SciencesMary Joy Dailo86% (21)

- Introduction To SociologyDocument34 pagesIntroduction To SociologyPeter MwenyaNo ratings yet

- Social Structure and DemographicsDocument9 pagesSocial Structure and DemographicsLoraine MakuletNo ratings yet

- Becoming Member of A SocietyDocument21 pagesBecoming Member of A SocietyCAINGLES, FELIZ ZOIENo ratings yet

- DISS - Lesson 5 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas in Social SciencesDocument37 pagesDISS - Lesson 5 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas in Social SciencesMary Joy DailoNo ratings yet

- For Print Chapter 1Document29 pagesFor Print Chapter 1Nm TurjaNo ratings yet

- Final SocDocument7 pagesFinal SoczeinabNo ratings yet

- SOC100 Test 1 NotesDocument16 pagesSOC100 Test 1 Notesbabaa boboNo ratings yet

- Understanding Social Problems - PPTDocument21 pagesUnderstanding Social Problems - PPTaneri patel100% (1)

- Understanding Culture Society and PoliticsDocument34 pagesUnderstanding Culture Society and PoliticsjenemeamileskimilatNo ratings yet

- Introductory Concepts in Sociology: Compiled by Anacoreta P. Arciaga Faculty Member-Social Sciences DepartmentDocument21 pagesIntroductory Concepts in Sociology: Compiled by Anacoreta P. Arciaga Faculty Member-Social Sciences DepartmentPalos DoseNo ratings yet

- Sociology NotesDocument38 pagesSociology NotesAyush Yadav67% (3)

- SOC101 Lecture Slides Week 2Document15 pagesSOC101 Lecture Slides Week 2maisha.ayman.75No ratings yet

- Page 3 Soc Sci 2Document1 pagePage 3 Soc Sci 2Hope Earl Ropia BoronganNo ratings yet

- C1 Study of SociologyDocument65 pagesC1 Study of Sociologysinagtala_86No ratings yet

- MODULE 1 SociologyDocument63 pagesMODULE 1 SociologyBhavya JhaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Midterms ExamDocument71 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics Midterms ExamNica de los SantosNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Sociology: Is An Invitation To Learn A New Way of Looking at Familiar Patterns of Social LifeDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Sociology: Is An Invitation To Learn A New Way of Looking at Familiar Patterns of Social LifeZia RehmanNo ratings yet

- Lecture December 19Document2 pagesLecture December 19iftikharmir355No ratings yet

- The Sociological Point of View Examining Social Life: Chapter 1, Section 1 Pages: 2-8Document15 pagesThe Sociological Point of View Examining Social Life: Chapter 1, Section 1 Pages: 2-8VJSevilla SevillaNo ratings yet

- Anthropology, Political Science and SociologyDocument13 pagesAnthropology, Political Science and Sociologyjeliena-malazarteNo ratings yet

- Ii-Sociological and AntrhopologicalDocument38 pagesIi-Sociological and Antrhopologicalroberto rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document12 pagesWeek 1Henry dragoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 13 1SGY141 Social InequalityDocument10 pagesLecture 13 1SGY141 Social InequalityowethuayandamthembuNo ratings yet

- Socio-Legal Dimensions of GenderDocument100 pagesSocio-Legal Dimensions of GenderFroilan TinduganNo ratings yet

- CommunityDocument28 pagesCommunityChelsea GraceNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument18 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsBenedicto PintorNo ratings yet

- Social ControlDocument28 pagesSocial ControlKeshav Singhmaar AryaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3-5 Positivist Soc SciDocument4 pagesLesson 3-5 Positivist Soc Scikimberson alacyangNo ratings yet

- Đề Cương Lý Thuyết Xã Hội HọcDocument14 pagesĐề Cương Lý Thuyết Xã Hội Họchoangminhdung2209No ratings yet

- The Concept of Social RolesDocument20 pagesThe Concept of Social RolesCarzo Aggy Mugy100% (1)

- Community Psychology ClassDocument179 pagesCommunity Psychology Classmeghna sarrafNo ratings yet

- Sociology Info& Culture NotesDocument16 pagesSociology Info& Culture NotesDanishNo ratings yet

- SociologyDocument6 pagesSociologyLinh Phan KhánhNo ratings yet

- Example Short Essays With Thesis StatementDocument3 pagesExample Short Essays With Thesis StatementAyu RegitaNo ratings yet

- Doctoral Degree in Civil and Environmental EngineeringDocument15 pagesDoctoral Degree in Civil and Environmental EngineeringThema ArrisaldiNo ratings yet

- Promotional Magazine-3 PDFDocument24 pagesPromotional Magazine-3 PDFsebastianmariusNo ratings yet

- OMSC-Form-COL-13-OBE-Syllabus - Principles of Teaching 2Document14 pagesOMSC-Form-COL-13-OBE-Syllabus - Principles of Teaching 2Amir M. VillasNo ratings yet

- The-influence-of-Artificial-Intelligence-Academically-in-Grade-12-students-of-AMABE 213Document18 pagesThe-influence-of-Artificial-Intelligence-Academically-in-Grade-12-students-of-AMABE 213aljhon.lerryNo ratings yet

- The Self & The Person in Contemporary AnthropologyDocument7 pagesThe Self & The Person in Contemporary AnthropologyRENARD CATABAYNo ratings yet

- CP 402 MBA IV Semester Project Format Jan 17 2012Document3 pagesCP 402 MBA IV Semester Project Format Jan 17 2012anon_78522331No ratings yet

- Matter WavesDocument25 pagesMatter WavesNarayan VarmaNo ratings yet

- Hedonic Treadmill 2Document4 pagesHedonic Treadmill 2rossana garciaNo ratings yet

- Scientific Misconduct PDFDocument14 pagesScientific Misconduct PDFCharlene KatiaNo ratings yet

- I Year April, 2019Document2 pagesI Year April, 2019J chandramohanNo ratings yet

- John M. Riddle - Eve's Herbs - A History of Contraception and Abortion in The West (1997, Harvard University Press) - Libgen - LiDocument349 pagesJohn M. Riddle - Eve's Herbs - A History of Contraception and Abortion in The West (1997, Harvard University Press) - Libgen - Lishabit montasirNo ratings yet

- Buteyko Breathing For Asthma (Protocol) : CochraneDocument7 pagesButeyko Breathing For Asthma (Protocol) : CochraneniyaNo ratings yet

- Resume Template Harvard StyleDocument2 pagesResume Template Harvard StyleEakkarat PattrawutthiwongNo ratings yet

- Perkembangan Teori Manajemen Dari Pemikiran Scientific Management Hingga Era Modern Suatu Tinjauan PustakaDocument20 pagesPerkembangan Teori Manajemen Dari Pemikiran Scientific Management Hingga Era Modern Suatu Tinjauan PustakaDian Sukmasari RahmahNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 8 Social Science History Notes Chapter 1 How When and WhereDocument2 pagesCBSE Class 8 Social Science History Notes Chapter 1 How When and WhereDhanya RamkumarNo ratings yet

- Bhabna De.: Computer Science & EngineeringDocument3 pagesBhabna De.: Computer Science & EngineeringVijay UrkudeNo ratings yet

- Trans 1 - BioethicsDocument2 pagesTrans 1 - BioethicsRencel Hope BañezNo ratings yet

- Dharmik Concept Gems For Knowledge WorkersDocument65 pagesDharmik Concept Gems For Knowledge WorkersKedar JonnalagaddaNo ratings yet

- Leader SelfsacrificeDocument15 pagesLeader SelfsacrificeHumayun Khalid100% (1)

- Rakovic Dejan - Arandjelovic Slavica - Micovic Mirjana - Quantum-Informational Medicine QIM 2011 PDFDocument150 pagesRakovic Dejan - Arandjelovic Slavica - Micovic Mirjana - Quantum-Informational Medicine QIM 2011 PDFPrahovoNo ratings yet

- Problem SolvingDocument361 pagesProblem SolvingIvan Espinobarros100% (2)

- Civil Engineering Topics V4Document409 pagesCivil Engineering Topics V4Ioannis MitsisNo ratings yet

- 7th Grade Cell Theory LessonDocument5 pages7th Grade Cell Theory Lessonapi-375487016No ratings yet

- Gned06 Syllabus STSDocument7 pagesGned06 Syllabus STSGianne Niña AmaroNo ratings yet

- FYBTech 2019-20 Sem-I TT PDFDocument21 pagesFYBTech 2019-20 Sem-I TT PDFShriniwas ApteNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet 10.1 Lesson Plan Template - 5E ModelDocument4 pagesActivity Sheet 10.1 Lesson Plan Template - 5E Modeleverlyn easterNo ratings yet