Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Econ - Unit - 9.2 - Incentive Analysis

Econ - Unit - 9.2 - Incentive Analysis

Uploaded by

Sampurnaa Das0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views19 pagesThe document discusses the concept of economic rationality which assumes that people prefer more to less and maximize net benefits. It describes the assumptions of substitutability, marginality, and fixed tastes and preferences. The document also discusses how economists use incentive analysis and the concepts of demand, supply, elasticity, costs and benefits, consumers' and producers' surplus to analyze how individuals and groups respond predictably to changes in costs and benefits. Optimal outcomes are achieved when marginal costs equal marginal benefits.

Original Description:

incentive analysis

Original Title

Econ_Unit_9.2_Incentive Analysis

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the concept of economic rationality which assumes that people prefer more to less and maximize net benefits. It describes the assumptions of substitutability, marginality, and fixed tastes and preferences. The document also discusses how economists use incentive analysis and the concepts of demand, supply, elasticity, costs and benefits, consumers' and producers' surplus to analyze how individuals and groups respond predictably to changes in costs and benefits. Optimal outcomes are achieved when marginal costs equal marginal benefits.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views19 pagesEcon - Unit - 9.2 - Incentive Analysis

Econ - Unit - 9.2 - Incentive Analysis

Uploaded by

Sampurnaa DasThe document discusses the concept of economic rationality which assumes that people prefer more to less and maximize net benefits. It describes the assumptions of substitutability, marginality, and fixed tastes and preferences. The document also discusses how economists use incentive analysis and the concepts of demand, supply, elasticity, costs and benefits, consumers' and producers' surplus to analyze how individuals and groups respond predictably to changes in costs and benefits. Optimal outcomes are achieved when marginal costs equal marginal benefits.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 19

Economic rationality

The concept of economic rationality has a specific

but simple meaning in economics.

It means that people prefer more to less and

maximise net benefits, whether utility, wealth, or

profits, as perceived by them.

This theory of rational choice is based on several

assumptions - substitutability, marginality and fixed

tastes and preferences.

Substitutability:

Goods are assumed substitutable one for the other (or

for money) at the margin. That is, there is a rate of

exchange (price) between any pair of goods that will

make an individual indifferent between them. This

notion of a trade-off is central to economic reasoning.

Marginality or equi-marginal principle: Maximising

implies equal- ising marginal values and diminishing

marginal returns - i.e. the equi- marginal principle. In

any activity, to obtain the maximum utility or profit

marginal values have to be equated.

The maximisation principle thus not only requires that

benefits exceed costs for each activity but that the level

of each activity be at a point where the marginal costs

of expanding the activity are equal to the marginal

benefits.

Fixed tastes and preferences:

The tastes' and preferences of individuals are

assumed to be given and stable. This assumption is

related to, and implied by, rational behaviour. If tastes

change over time or with past choices, preferences may

not be consistent.

Economists believe that groups react in a predictable way to

changes in the costs and benefits of the options they face.

This incentive analysis is a direct implication of the

rationality assumption.

As a result prices and laws are primarily viewed as creating

incentives which alter behaviour and outcomes.

Incentive analysis is formalised by the economists‘ as 'laws'

of demand and supply. These are 'laws' in the sense that

they describe observed regularities in behaviour and

outcomes. The 'law' of demand states that when the price of

a good or service, increases, all other things equal, less is

purchased.

• The economic approach applies incentive analysis to

all economic and non-economic activities.

• incentive analysis has wide application - in drug

dealing, prostitution, crime, adoption, sale of body

parts, marriage, divorce, illegal immigrants, armies and

so on.

• Economics simply formalises the demand and supply

conditions operating in these activities and, most

importantly, works through the implications of how

changes in economic and non-economic factors affect

the willingness of people to demand and supply the

activity under consideration.

The economists' incentive analysis can be illustrated by the law

restricting the speed limit. Most people, even those who would regard

themselves as law abiding, break the speed limit from time to time. If

there is 110 penalty, people will speed if the benefits they derive at the

time exceed the likely costs in terms of the potential likelihood of an

accident and its consequences to others and themselves.

If a penalty is imposed, the costs of breaking the speed limit rises and,

all things equal we expect that fewer people will speed. Drivers will

take into account not only the inherent risks, benefits and costs, but

also the potential penalties - the fine, the loss of their Licence and the

impact of a conviction on their insurance payments.

As the penalties get greater, most people, even non-economists, would

agree that less and less speeding will occur. More people will speed if

the penalty is £10 than if it is £20,000! This is informal economic

modelling.

In looking at the world in this way one is conscious

of the fact that the 'price up/quantity demanded down'

prediction may not apply to all, or even a large

number, of people. If the penalty for speeding (or the

price of bread) goes up 5 per cent or 10 per cent

many people will simply take it in their stride and not

modify their behaviour.

If the courts mete out more severe punishment some,

maybe many, criminals will simply go on as before.

Does this undermine the economises' incentive

analysis?

Incentive analysis does not assume that every

individual reacts to a curb on his or her actions. Some

will react by reducing their participation or cease

altogether; others will not.

But all that is required for, say, fines, to deter is that a

subset of those who previously speed now decide not

to, or to do so less frequently. To put it more

graphically, criminals at the margin will be deterred by

higher penalties; not the psychopath or deranged serial

killer." It is the reaction of some that generates the

response predicted by the economists' rationality

model: clearly, the greater the number sensitive to

increases in fines or cost the greater the reaction.

It is often useful to know not only whether an increase

in penalties or costs deters or reduces a particular

activity, but by how much.

A quantitative measure of the incentive effects of a

change in price, cost or legal sanction is known as its

elasticity.

This measures the proportionate response to 1per cent

increase/decrease in the price/cost/sanction. An

elasticity of minus 1(-1)would mean that a 1 per cent

increase in, say, the penalty imposed on criminals leads

to a fall (hence the minus) of 1 per cent in the number

of crimes. A higher elasticity indicates greater

responsiveness.

Economics used the measuring rod of money to

evaluate economic and legal outcomes. It thus places

heavy reliance on assessing the costs and benefits of

the law, considerations that will always be relevant

when resources are limited.

• Economic value or benefits are measured by the

'willingness-to-pay' (WTP) of those individuals who

are affected.

• That is, the economist's notion of benefit is similar to

the utilitarian notion of happiness but it is happiness

backed by WTP. Mere desire or 'need' is not relevant.

WTP provides a quantitative indication of the intensity

of individual preferences.

The consumers' surplus -which is the difference

between the maximum willingness to pay of all

consumers' above the price.

The producers' surplus is the difference between the

costs of production including a reasonable profit and

the price. It is shown by the unshaded triangle below

the cousumners' surplus.

By framing the question in this way the economist is able to

adopt a consistent valuation procedure - one which takes

into account the preferences of those whose lives are at risk

and the society's ability to devote resources to reduce risks -

i.e. buy more safety. This simple calculation provides

guidance on the vexing question of‘ How safe is safe?' or, in

a legal context, 'What is reasonable care?' Optimal care is

achieved when an additional pound, euro, or dollar spent on

reducing risks saves a pound, euro or dollar in expected

accident losses. 'Optimal' defined in this way means that

many accidents are 'justified' - because they would be too

costly to avoid. The corollary to this is that just as there can

be too little care, there can be excessive care.

The distinction between a real cost and a wealth

transfer can be illustrated by the impact of a

Government (ad valorem) sales tax on a good. This tax

generates revenues for the Government; each time a

unit of the good is bought, wealth is transferred from

consumers to the government.

This transfer is not a cost since the consumers' loss is the

Government's (taxpayers') gain. These losses and gains net out,

provided that the government does not waste the money on

activities which generate negative consumers' surplus. However, the

increase in the tax-inclusive price causes consumers to buy less of

the now more expensive good.

This has two effects: society saves the resources that would have

otherwise been used to produce the lost output (a gain), but loses the

consumers' (and producers') surplus above these (marginal) costs of

production. It is this lost economic surplus - which economists refer

to as the 'deadweight loss' - that is the real economic cost of the tax:

it is the inefficiency generated by the way the tax distorts

consumption decisions.

By casting the problem in this way it should be immediately

obvious that this 'cost' is not registered in the marketplace as such.

The real cost of a tax, law, or any other policy that distorts prices in

an economy is given by the value of the output not produced and

consumed.

Thus the valuation of economic costs and benefits must often

proceed on the basis counterfactual or 'but for' analysis - 'but for'

the specific law in question what would have been the costs and

benefits?

You might also like

- Most Frequently Used HotkeysDocument6 pagesMost Frequently Used HotkeysCarlos Ferreira100% (1)

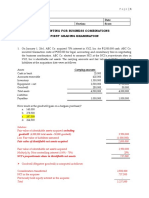

- Accounting For Business Combinations First Grading ExaminationDocument18 pagesAccounting For Business Combinations First Grading Examinationjoyce77% (13)

- Singapore Airlines Limited: SWOT AnalysisDocument9 pagesSingapore Airlines Limited: SWOT AnalysisDarshil ShahNo ratings yet

- Test Bank MGMT 126Document8 pagesTest Bank MGMT 126najihachangminNo ratings yet

- H3 Theme 1 Assignment Suggested AnswerDocument6 pagesH3 Theme 1 Assignment Suggested Answer23S46 ZHAO TIANYUNo ratings yet

- The Economics of PenaltiesDocument13 pagesThe Economics of PenaltiesCore ResearchNo ratings yet

- GDP-The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross Domestic Income (GDI) Is The Amount ofDocument4 pagesGDP-The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross Domestic Income (GDI) Is The Amount ofluna.razia8812No ratings yet

- Chapter 6: Reporter: Caballero, DianneDocument14 pagesChapter 6: Reporter: Caballero, Dianne박니치No ratings yet

- Mankiw's "Ten Principles of Economics": How People Make DecisionsDocument3 pagesMankiw's "Ten Principles of Economics": How People Make DecisionsmadskillzNo ratings yet

- The Consequences of Taxation: © 2006 Social Philosophy & Policy Foundation. Printed in The USADocument15 pagesThe Consequences of Taxation: © 2006 Social Philosophy & Policy Foundation. Printed in The USAkdrtkrdglNo ratings yet

- MicroeconomicsDocument6 pagesMicroeconomicsSriranjani SureshNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics Chapter-Two: Theory of DemandDocument37 pagesManagerial Economics Chapter-Two: Theory of Demandabey.mulugetaNo ratings yet

- Conspectus International EconomicsDocument22 pagesConspectus International EconomicsРоберт МкртчянNo ratings yet

- JawapanDocument13 pagesJawapanmsfaziah.hartanahNo ratings yet

- Managerial Eco q-4Document9 pagesManagerial Eco q-4Ritik katochNo ratings yet

- Micro Economics 2Document9 pagesMicro Economics 2kunwarsundar62No ratings yet

- 02045-Tortliabilitysystem Apr02Document19 pages02045-Tortliabilitysystem Apr02losangelesNo ratings yet

- Taxation (Contribution)Document8 pagesTaxation (Contribution)Suciu IuliaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Microeconomics F1 Accountant in Business ACCA Qualification Students ACCA GlobalDocument1 pageIntroduction To Microeconomics F1 Accountant in Business ACCA Qualification Students ACCA Globalnajmi ahmadNo ratings yet

- Fall 2017Document11 pagesFall 2017Kripaya ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Psychic Cost of Tax EvasionDocument5 pagesPsychic Cost of Tax EvasionMohammad Shahjahan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Business Economics BCADocument25 pagesBusiness Economics BCAamjoshuabNo ratings yet

- After Reading Chapter 5Document1 pageAfter Reading Chapter 5kapsegunjanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 SummaryDocument8 pagesChapter 1 SummaryTejpal LathherNo ratings yet

- Steps of CostDocument5 pagesSteps of Costleonxchima SmogNo ratings yet

- MicroeconomicsDocument35 pagesMicroeconomicsRaghu Ram100% (1)

- Economic Policy Assignment 1Document9 pagesEconomic Policy Assignment 1Harry DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- Legal Entity State: Government ActivityDocument3 pagesLegal Entity State: Government ActivityEunice Bucao BuesaNo ratings yet

- Klazar AJDocument14 pagesKlazar AJapi-3716466No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Introduction To EconomicsDocument8 pagesAssignment 1 Introduction To Economicsdmpp55676No ratings yet

- What Is MicroeconomicsDocument6 pagesWhat Is MicroeconomicsjuliaNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument6 pagesEconomicsmeighantoffeeNo ratings yet

- Economic Functions of GovernmentDocument9 pagesEconomic Functions of GovernmentshahidulislamtaluckderNo ratings yet

- BIT 2120 Econ Notes 1Document24 pagesBIT 2120 Econ Notes 1kelvinkakuru2No ratings yet

- Marginalist School of Economic ThoughtDocument7 pagesMarginalist School of Economic ThoughtSalawu SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 M1Document9 pagesChap 2 M1science boyNo ratings yet

- The Goals and Strategies of Financial RegulationDocument29 pagesThe Goals and Strategies of Financial Regulationsara jessicaNo ratings yet

- How Microeconomics Will Help You As A Lawyer in Future: From:-Divyanshi Gupta Bba LLBDocument19 pagesHow Microeconomics Will Help You As A Lawyer in Future: From:-Divyanshi Gupta Bba LLBManglam GuptaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Limits, Alternatives and ChoicesDocument9 pagesChapter 1 - Limits, Alternatives and ChoicesTrixy FloresNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDocument4 pagesBachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDave EscalaNo ratings yet

- A6 - ECON 119-1 - Osunero, Leanzy JenelDocument5 pagesA6 - ECON 119-1 - Osunero, Leanzy Jenelleanzyjenel domiginaNo ratings yet

- SM Econ 05 Micro Ch05Document24 pagesSM Econ 05 Micro Ch05senrucatNo ratings yet

- Price ActDocument5 pagesPrice ActJohny TumaliuanNo ratings yet

- Chapter Review 7Document3 pagesChapter Review 7Tória RajabecNo ratings yet

- Theories of Tax Shifting& IncidenceDocument8 pagesTheories of Tax Shifting& IncidenceSamruddhiNo ratings yet

- Theories of Tax Incidence and ShiftingDocument4 pagesTheories of Tax Incidence and Shiftinganushkajaiswal2002No ratings yet

- BIT 2120 Econ Notes 1Document23 pagesBIT 2120 Econ Notes 1Onduso Sammy MagaraNo ratings yet

- Definition of Economics WWWWDocument5 pagesDefinition of Economics WWWWSonu KumarNo ratings yet

- Framework of Financial Management Week 3 Part 1Document5 pagesFramework of Financial Management Week 3 Part 1Louie Ann CasabarNo ratings yet

- BHM 111.1Document7 pagesBHM 111.1kelvinavurili03No ratings yet

- What Is Economic RegulationDocument5 pagesWhat Is Economic RegulationSyril PujanteNo ratings yet

- Purposes and EffectsDocument16 pagesPurposes and EffectsChelle OcampoNo ratings yet

- ECON1101: Microeconomics 1: Chapter 1: Thinking As An EconomistDocument14 pagesECON1101: Microeconomics 1: Chapter 1: Thinking As An EconomistmaustroNo ratings yet

- A Primer On Antitrust DamagesDocument59 pagesA Primer On Antitrust DamagesOleksiy KuntsevychNo ratings yet

- Untitled 2Document4 pagesUntitled 2Luddu MinhNo ratings yet

- Economic ProblemsDocument26 pagesEconomic Problemschaitu34100% (4)

- Chapter 1 & 2 Ten Principles of Economics and Thinking Like An EconomistDocument92 pagesChapter 1 & 2 Ten Principles of Economics and Thinking Like An EconomistNaeemullah baigNo ratings yet

- Economics Chapter 5 SummaryDocument6 pagesEconomics Chapter 5 SummaryAlex HdzNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 ECONOMICS Notes MBADocument5 pagesUNIT 1 ECONOMICS Notes MBAMegha ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Economic Principles Assist in Rational Reasoning and Defined ThinkingDocument3 pagesEconomic Principles Assist in Rational Reasoning and Defined Thinkingdodialfayad9665No ratings yet

- Managerial NotesDocument7 pagesManagerial NotesCJ ReynoNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument145 pagesEconomicsSaeed WataniNo ratings yet

- Economic, Business and Artificial Intelligence Common Knowledge Terms And DefinitionsFrom EverandEconomic, Business and Artificial Intelligence Common Knowledge Terms And DefinitionsNo ratings yet

- Econ Unit I Demand and SupplyDocument49 pagesEcon Unit I Demand and SupplySampurnaa DasNo ratings yet

- Econ - Unit - 5 - Cost TheoryDocument39 pagesEcon - Unit - 5 - Cost TheorySampurnaa DasNo ratings yet

- Econ - Unit - 2 - Consumer Demand TheoryDocument36 pagesEcon - Unit - 2 - Consumer Demand TheorySampurnaa DasNo ratings yet

- Econ - Unit - 4 - Production Theory.Document47 pagesEcon - Unit - 4 - Production Theory.Sampurnaa DasNo ratings yet

- PART - II - Market StructureDocument35 pagesPART - II - Market StructureSampurnaa DasNo ratings yet

- Golf Logix: Measuring The Game of Golf: Written Analysis of CaseDocument3 pagesGolf Logix: Measuring The Game of Golf: Written Analysis of CaseNimrah ZubairyNo ratings yet

- ASF - Youth Empowerment Initiative (Poster)Document2 pagesASF - Youth Empowerment Initiative (Poster)Burton MwakilasaNo ratings yet

- Taxation Management - CourseworkDocument9 pagesTaxation Management - CourseworkKamauWafulaWanyamaNo ratings yet

- QM Awards FrameworkDocument12 pagesQM Awards FrameworkSrinivasan JeganNo ratings yet

- JPM Investment Outlook For 2023Document14 pagesJPM Investment Outlook For 2023Igor BielikNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Risk ManagementDocument91 pagesIntroduction To Risk Managementaiman afiqNo ratings yet

- Remote Working and Work Life BalanceDocument16 pagesRemote Working and Work Life BalanceDwayne DevonishNo ratings yet

- Vietnam 2023q4 CW Market Beat Hanoi - en CombinedDocument36 pagesVietnam 2023q4 CW Market Beat Hanoi - en CombinedVu Ha NguyenNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentAalizae Anwar YazdaniNo ratings yet

- Ekonomi Teknik - Tugas 2Document12 pagesEkonomi Teknik - Tugas 2HanliWijayaNo ratings yet

- NEFT Mandate Form - Effective From Aug 2012Document1 pageNEFT Mandate Form - Effective From Aug 2012Mohan VarkeyNo ratings yet

- Thanapriya SOP - CompressedDocument7 pagesThanapriya SOP - CompressedlkayoungcplNo ratings yet

- AIS - Problem Set - Session 12Document3 pagesAIS - Problem Set - Session 12qonitahmutNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001 in A NutshellDocument4 pagesISO 9001 in A Nutshelliamvanes0% (1)

- About Rtgs & NeftDocument5 pagesAbout Rtgs & NeftAbdulhussain JariwalaNo ratings yet

- Upto 1000 Solved MCQs of MKT501 Marketing Management WWW - VustudentsDocument228 pagesUpto 1000 Solved MCQs of MKT501 Marketing Management WWW - VustudentsLyla Abbas Khan100% (24)

- HSC Business Studies Syllabus AcronymsDocument9 pagesHSC Business Studies Syllabus AcronymsmissgroganNo ratings yet

- HRPDocument7 pagesHRPAmro Ahmed RazigNo ratings yet

- SAP Certified Application Associate - Financial Accounting With SAP ERP - FullDocument41 pagesSAP Certified Application Associate - Financial Accounting With SAP ERP - FullMohammed Nawaz ShariffNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment Ib1704 Phuong Oanh Sa160135Document14 pagesIndividual Assignment Ib1704 Phuong Oanh Sa160135Hoa PhươngNo ratings yet

- John Ervin Bonilla Bsba Fm2B 1. Admission by Purchase of InterestDocument8 pagesJohn Ervin Bonilla Bsba Fm2B 1. Admission by Purchase of InterestJohn Ervin Bonilla100% (4)

- Agriclinics and Agribusiness CentersDocument47 pagesAgriclinics and Agribusiness CentersMadhavilathaNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document19 pagesCH 1Ak AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Driving Innovations in Infrastructure:: The Startup WayDocument66 pagesDriving Innovations in Infrastructure:: The Startup WaydipmalaNo ratings yet

- Reverse Innovation A Global Growth Strategy That Could Pre-Empt Disruption at HomeDocument9 pagesReverse Innovation A Global Growth Strategy That Could Pre-Empt Disruption at HomePitaloka RanNo ratings yet

- Distinction Between Promissory Note and Bill of ExchangeDocument5 pagesDistinction Between Promissory Note and Bill of ExchangeZeesahnNo ratings yet