Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Company Dividend Policy

Company Dividend Policy

Uploaded by

truthoverlove0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views10 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views10 pagesCompany Dividend Policy

Company Dividend Policy

Uploaded by

truthoverloveCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 10

Module 8

Company Dividend Policy

Dividend Irrelevancy I

• There is a set of arguments that says that the dividend decision of a

company is unimportant; that nothing the company does in the way

of paying or not paying a dividend has any effect upon the wealth

of its shareholders. See Simple corporation on page 8/2.

• Higher cash dividends mean lower market value to existing

shareholders, and lower cash dividends mean higher market value

to existing shareholders. This is common to all dividend policy

changes when other financial decisions are to be held the same.

• If existing shareholder dividends are reduced, their claim upon

future dividends, and thus current market value, is higher because

less new equity is raised. If existing shareholder dividends are

increased, their claim upon future dividends, and thus current

market value, is lower because more new shares must be sold.

• Link between dividend policy and investment decision.

Dividend Irrelevancy I

• In summary, the notion of dividend irrelevancy argues

as follows: leaving other financial decisions intact,

higher dividends require more new shares to be sold,

lower dividends require fewer. As long as the new

shareholders insist upon receiving full value for the

cash they contribute, and company share value in total

is unchanged (because other decisions are intact),

existing shareholder wealth is unaffected by the

dividend decision. Any change in the cash portion of

current shareholder wealth (due to changes in cash

dividends) will be exactly offset by changes in the value

of their shareholdings (due to changes in the amounts

of new shares issued by the company).

Dividends and Market Frictions

• Taxes, transaction costs and flotation costs.

• Taxation of Dividends

• When a company pays a dividend, the cash thus distributed must

make its way through whatever tax system exists in the economy

before the dividend is useful to the shareholder. From the

shareholder’s perspective, it is after tax (both company and

personal) dividends that are of interest. It is generally the case,

however, that dividends are more heavily taxed than capital gains.

In countries where the amounts of cash available to pay dividends

are net of company taxes, and the dividends paid are taxed again at

the shareholder level, dividend payment to taxable shareholders is

expensive. Those shareholders would likely be better off receiving

their wealth in the form of share price increases that are either not

taxed or taxed at lower rates than the dividends.

• See table 8.2.

Dividends and Market Frictions

• Transaction Costs of Dividend Payments

• In real markets, shareholders cannot shift costlessly

between shares and cash. There are usually brokerage

fees to be paid when such transactions take place.

(And there may be the forced ‘realisation’ of capital

gains and the taxes thereby due.) So shareholders may

prefer one dividend policy to another depending upon

their preferences for consuming wealth across time

and the costs they would pay to achieve the desired

consumption pattern, given a particular dividend policy

by the company.

Dividends and Market Frictions

• Flotation Costs

• Companies themselves incur costs in raising

money from capital markets when they pay

dividends so high as to require new shares to be

sold. These are called flotation costs, and they

can be significant for the issuance of new shares,

depending upon the mechanism of sale. If

intermediaries such as investment bankers are

used, the costs can be as high as 5 to 25 per cent

of the total value of issued shares.

• Residual Dividend Policy

Dividend Clienteles: Irrelevancy II

• It is important to recognise that shareholders are not all alike in the

exposure they have to dividend and capital gains taxation and that

preferences for consumption of wealth across time differ. One type

of shareholder, say those in high personal tax brackets, would

prefer one kind of dividend policy (low cash payout), whereas

another kind of shareholder in a low tax bracket might well prefer

high cash payout.

• Such different kinds of shareholders have come to be called

clienteles in finance. The interpretation is that they comprise

groups that would be willing to pay extra to get the type of

dividend policy that is best suited to their own tax and consumption

preferences. In other words, they may have probably been

attracted to the shares of a company that pursues a policy that to

them is attractive.

Dividend Clienteles: Irrelevancy II

• There are not just a few companies providing wealth

disbursements to shareholders; there are many. And

those companies provide a wide range of dividend

strategies to the market. Given the number and types

of dividend payout patterns available, we can raise

questions as to whether anything a particular company

can do to change its dividend policy is likely to give its

shareholders something that they could not acquire

elsewhere. This idea is one of the underpinnings of

current thinking about company dividend policy, and it

brings us back to the original ‘irrelevancy’ conclusion,

even in realistic financial markets.

Dividends and Signalling

• One of the empirical findings about company

dividends is that these cash payouts seem to be

more stable in monetary terms across time than

any particular residual or clientele hypothesis for

dividend policy can explain. Company financial

managers seem to be loath to pay a dividend

unless they think it can be sustained for some

period of time by the expected cash flows of the

firm. One explanation for the ‘smoothing’ across

time of company dividends that seems more

reasonable is the signalling value of dividends.

Dividends and Share Repurchase

• Reasons given for repurchase

1) undertaken so as to have shares for various uses (merger

and acquisition purposes, employee stock option exercise,

and so forth);

2) very often the company will announce that it considers its

shares ‘underpriced’ and thus a good investment, and is

therefore investing in itself.

• Real reason: Share repurchases are nothing more than a

cash dividend to shareholders. If all shareholders sell back

to the company the same proportion of their holdings, it is

easy to see that the net effect is to shift cash from the

company to shareholders, leaving undisturbed the

proportional claim of each shareholder.

You might also like

- Theories of Financial ManagementDocument5 pagesTheories of Financial ManagementZehraAbdulAzizNo ratings yet

- Review Test Submission: Practice Quiz 1 - Module 1: Quizzes and TestsDocument97 pagesReview Test Submission: Practice Quiz 1 - Module 1: Quizzes and TestsPalak MehtaNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Dividend Decision/PolicyDocument38 pagesChapter Three: Dividend Decision/PolicyMikias DegwaleNo ratings yet

- VC - Finm7312 Slides # 3Document24 pagesVC - Finm7312 Slides # 3Phumzile MahlanguNo ratings yet

- Lecture No. 20Document13 pagesLecture No. 20Ali Asad BaigNo ratings yet

- Lecture No. 22 (R)Document21 pagesLecture No. 22 (R)Ali Asad BaigNo ratings yet

- Dividend Decisions - Dividend PolicyDocument24 pagesDividend Decisions - Dividend PolicyTIBUGWISHA IVANNo ratings yet

- Sharing Firm WealthDocument3 pagesSharing Firm WealthJohn Jasper50% (2)

- Dividend PolicyDocument35 pagesDividend PolicyBhavesh JainNo ratings yet

- DEVIDEND DICISION... HDFC Bank-2015Document64 pagesDEVIDEND DICISION... HDFC Bank-2015Tanvir KhanNo ratings yet

- A Study On Dividend PolicyDocument75 pagesA Study On Dividend PolicyVeera Bhadra Chary ChNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy AfmDocument10 pagesDividend Policy AfmPooja NagNo ratings yet

- Unit Iv-1Document8 pagesUnit Iv-1Archi VarshneyNo ratings yet

- Dividends and Dividend PolicyDocument30 pagesDividends and Dividend PolicyAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy NotesDocument6 pagesDividend Policy NotesSylvan Muzumbwe MakondoNo ratings yet

- Unit 18 Dividend Decisions: ObjectivesDocument10 pagesUnit 18 Dividend Decisions: ObjectivesShriniwash MishraNo ratings yet

- FinmanDocument7 pagesFinmanNHEMIA ELEVENCIONADONo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument10 pagesDividend PolicyShivam MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Gitman c14 SG 13geDocument13 pagesGitman c14 SG 13gekarim100% (3)

- RM Assignment-3: Q1. Dividend Policy Can Be Used To Maximize The Wealth of The Shareholder. Explain. AnswerDocument4 pagesRM Assignment-3: Q1. Dividend Policy Can Be Used To Maximize The Wealth of The Shareholder. Explain. AnswerSiddhant gudwaniNo ratings yet

- Distribution To ShareholdersDocument47 pagesDistribution To ShareholdersVanny NaragasNo ratings yet

- Finance Term Paper (Ratio Analysis)Document13 pagesFinance Term Paper (Ratio Analysis)UtshoNo ratings yet

- AC 16-11 Accounting-G1Document5 pagesAC 16-11 Accounting-G1faris prasetyoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Dividend PolicyDocument32 pagesChapter Four Dividend PolicydanielNo ratings yet

- Orion PharmaDocument20 pagesOrion PharmaShamsun NaharNo ratings yet

- FM ReportDocument14 pagesFM ReportyanaNo ratings yet

- FM II - Chapter 02, Divided PayoutDocument35 pagesFM II - Chapter 02, Divided PayoutKalkidan G/wahidNo ratings yet

- C-5 Dividend Policy 3rdDocument12 pagesC-5 Dividend Policy 3rdsamuel debebeNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Dividend PolicyDocument26 pagesPresentation On Dividend PolicygeoffmaneNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document10 pagesModule 2rajiNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy and Value of FirmDocument3 pagesDividend Policy and Value of FirmSaadNo ratings yet

- Dividend Decisions-1Document24 pagesDividend Decisions-1TIBUGWISHA IVANNo ratings yet

- FM 5Document10 pagesFM 5Rohini rs nairNo ratings yet

- FINANCE MANAGEMENT FIN420 CHP 12Document18 pagesFINANCE MANAGEMENT FIN420 CHP 12Yanty IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy, Chapter 17Document22 pagesDividend Policy, Chapter 17202110782No ratings yet

- Payout Policy: Suggested Answer To Opener-in-Review QuestionDocument15 pagesPayout Policy: Suggested Answer To Opener-in-Review QuestionChoudhry TradersNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument26 pagesDividend PolicyAnup Verma100% (1)

- Unit 5 Financial Management Complete NotesDocument17 pagesUnit 5 Financial Management Complete Notesvaibhav shuklaNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy: Answers To Concept Review QuestionsDocument6 pagesDividend Policy: Answers To Concept Review Questionsmeselu workuNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument47 pagesDividend PolicyniovaleyNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument15 pagesDividend PolicyhunterayskaumeNo ratings yet

- CH 14 - Mini Case - 23845Document11 pagesCH 14 - Mini Case - 23845Aamir KhanNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy.: The Choice Between Distribution and RetentionDocument21 pagesDividend Policy.: The Choice Between Distribution and RetentionSADAK MOHAMED IBRAHIMNo ratings yet

- Distribution To ShareholdersDocument47 pagesDistribution To Shareholderszyra liam stylesNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policies and DecisionsDocument19 pagesDividend Policies and Decisionsdushime delphineNo ratings yet

- Study of Dividend Payout PatternDocument27 pagesStudy of Dividend Payout PatternVivekNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument13 pagesDividend PolicyMohammad MoosaNo ratings yet

- Dividend DecisionsDocument32 pagesDividend DecisionstekleyNo ratings yet

- Dividend Is The Portion of Earnings Available To Equity Shareholders That Equally (Per Share Bias) Is Distributed Among The ShareholdersDocument21 pagesDividend Is The Portion of Earnings Available To Equity Shareholders That Equally (Per Share Bias) Is Distributed Among The ShareholdersKusum YadavNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy: Chapter ObjectivesDocument2 pagesDividend Policy: Chapter ObjectivesMundixx TichaNo ratings yet

- Payout PolicyDocument9 pagesPayout PolicyFirman Nur ZulfikarNo ratings yet

- Topic 10 Dividend Policy (Chapter 16, Brealey) : Information Content of Stock RepurchasesDocument8 pagesTopic 10 Dividend Policy (Chapter 16, Brealey) : Information Content of Stock RepurchasesHashashahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 SummaryDocument8 pagesChapter 18 SummaryCyrilla NaznineNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy (S)Document3 pagesDividend Policy (S)Nahian ShalimNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14-1Document73 pagesChapter 14-1Naeemullah baigNo ratings yet

- Dividend Decisions: © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of IndiaDocument29 pagesDividend Decisions: © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Indiamovies villa hit hai broNo ratings yet

- Dividend DecisionzxDocument0 pagesDividend Decisionzxsaravana saravanaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance BasicsDocument27 pagesCorporate Finance BasicsAhimbisibwe BenyaNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy AssignmentDocument8 pagesDividend Policy Assignmentgeetikag2018No ratings yet

- Dividend Investing for Beginners & DummiesFrom EverandDividend Investing for Beginners & DummiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Dividend Investing: Passive Income and Growth Investing for BeginnersFrom EverandDividend Investing: Passive Income and Growth Investing for BeginnersNo ratings yet

- Company Capital StructureDocument11 pagesCompany Capital StructuretruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Financial EngineeringDocument14 pagesFinancial EngineeringtruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Company Investment DecisionsDocument10 pagesCompany Investment DecisionstruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Earnings, Profit and Cash FlowDocument6 pagesEarnings, Profit and Cash FlowtruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Options, Agency, DerivativesDocument10 pagesOptions, Agency, DerivativestruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Working Capital ManagementDocument12 pagesWorking Capital ManagementtruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Estimating CashflowsDocument3 pagesEstimating CashflowstruthoverloveNo ratings yet

- Boomerang Arbitrage PresentationDocument26 pagesBoomerang Arbitrage Presentationseemsaroj007100% (1)

- My Trading DayDocument4 pagesMy Trading DayJacob CodjoNo ratings yet

- A4 Growealth Survey Oct 2020 PDFDocument1 pageA4 Growealth Survey Oct 2020 PDFAlois KudzaiNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of Money Manager CapitalismDocument38 pagesThe Rise and Fall of Money Manager CapitalismtymoigneeNo ratings yet

- Asset Management Manual A Guide For Practitioners: PlanningDocument71 pagesAsset Management Manual A Guide For Practitioners: Planningjorge GUILLENNo ratings yet

- SOCAP 10th Anniversary BookletDocument84 pagesSOCAP 10th Anniversary BookletSocial Capital Markets100% (1)

- Open Market OperationsDocument4 pagesOpen Market OperationsWickedadonisNo ratings yet

- Certificate in Investment Management - Cert ImDocument4 pagesCertificate in Investment Management - Cert ImbabsoneNo ratings yet

- Birchwood III Investment Summary OPENDocument1 pageBirchwood III Investment Summary OPENthepthikonedNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary Company BackgroundDocument5 pagesExecutive Summary Company BackgroundRhea AngelicaNo ratings yet

- Kras LK TW Iv 2018 PDFDocument229 pagesKras LK TW Iv 2018 PDFRifda FauziyahNo ratings yet

- S3.1 Financial Accounting-QPDocument12 pagesS3.1 Financial Accounting-QPaiza eroyNo ratings yet

- ITC Financial Result Q4 FY2021 CfsDocument8 pagesITC Financial Result Q4 FY2021 CfsKaushik ViswanathanNo ratings yet

- D:/handout/ipo WPDDocument7 pagesD:/handout/ipo WPDNikita JassujaNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure of DR Reddy's LaboratoriesDocument11 pagesCapital Structure of DR Reddy's LaboratoriesNikhil KumarNo ratings yet

- PROJECT - Joining The MarketDocument5 pagesPROJECT - Joining The Marketrobr5604No ratings yet

- Sap Fi Gen FinperformanceDocument14 pagesSap Fi Gen FinperformanceRavi Chandra LNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document23 pagesChapter 9Hamis Rabiam MagundaNo ratings yet

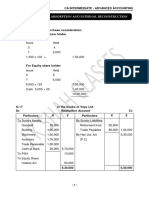

- 5 Amalgamation, Absorption and External Reconstruction - HomeworkDocument21 pages5 Amalgamation, Absorption and External Reconstruction - HomeworkYash ShewaleNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes International Finance PrintedDocument47 pagesLecture Notes International Finance PrintedPurnima PuriNo ratings yet

- Aurum Hedge Fund Industry Deep Dive - 2021 ReviewDocument33 pagesAurum Hedge Fund Industry Deep Dive - 2021 ReviewJagdeep MaviNo ratings yet

- Financial Management September 2012 Marks Plan ICAEWDocument8 pagesFinancial Management September 2012 Marks Plan ICAEWMuhammad Ziaul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Finity Stock Investing EbookDocument15 pagesFinity Stock Investing Ebookindranil mukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Value at RiskDocument11 pagesValue at RiskRashmiroja SahuNo ratings yet

- Forex and Gold Market CourseDocument32 pagesForex and Gold Market CourseBaqar Zaidi100% (3)

- MCQ Advanced Financial ManagementDocument3 pagesMCQ Advanced Financial ManagementBasappaSarkar78% (36)

- The Investments and Securities Act 2007 NigeriaDocument165 pagesThe Investments and Securities Act 2007 NigeriaIbi MbotoNo ratings yet

- Financial Planning and WM Assignment 2Document4 pagesFinancial Planning and WM Assignment 2Nishok NagamaniNo ratings yet

- Dealership PropsalDocument7 pagesDealership PropsalAnkitNo ratings yet