Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Epistemology 9 - Descarte and Scepcitism

Epistemology 9 - Descarte and Scepcitism

Uploaded by

Trung0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views20 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views20 pagesEpistemology 9 - Descarte and Scepcitism

Epistemology 9 - Descarte and Scepcitism

Uploaded by

TrungCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 20

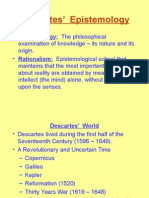

Epistemology 9

Descartes and Scepticism

Epistemology and Scepticism

• Beginning with Descartes (1596-1650), epistemology has two aspects:

(1) It seeks to define what is knowledge is and (2) it seeks to clarify

how knowledge is gained – usually as a defense against scepticism.

• The first gives us a definition of knowledge; the second gives us a

method for attaining knowledge to defeat the sceptic!

• Because of Descartes, modern epistemology faces the problem of

scepticism. In fact, we could classify various types of epistemology by

their responses to scepticism.

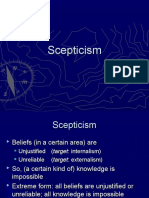

• Scepticism is a form of philosophical doubt about the very possibility of

knowledge. It calls into question whether any of our beliefs about the

world could ever be justified, or proved beyond doubt.

• Scepticism claims: Knowledge is Impossible based on our philosophical

definition -

The target of philosophical scepticism is the

external world outside the mind (brain)

• The Sceptical Argument:

• (1) p = any proposition about the mind-

independent empirical world (e.g. I am sitting

in a lecture theatre, I have hands, grass is

green, etc.)

• (2) (S) Then, for any S, S cannot know that p

Descartes’ Project

• “I have always thought that two questions - that of God and that of

the soul - are chief among those that ought to be demonstrated by

the aid of philosophy rather than of theology.”

• “. . . certainly no unbeliever seems capable of being persuaded of

any religion or even of moral virtue, unless these two are first

proven to him by natural reason.” [Meditations, Letter to the

Theology Faculty, §1-2] – “the light of reason” = unrevealed

reasoning – not Revelation – principle of autonomy (Kant): “think

for yourself!” freedom of the mind

• Note: what does Descartes mean by “natural reason”?

• A rational faculty of proof and demonstration = (justifying belief)

independent of faith/theology. How does it function?

• How does reason break out of the circle of faith (religious belief)?

• Descartes’ conclusion is that reason grounds itself without faith or

theology with the aid of epistemology – the foundation of

philosophy, foundation of ontology/metaphysics (Kant agrees)

Descartes’ Doubt:

autonomy or authority?

• “. . . I realized how many were the false opinions that in my youth I

took to be true, and thus how doubtful were all the things that I

subsequently built upon these opinions.” Jesuit College at “La

Flèche”

• “. . . I realized that for once I had to raze [tear down or destroy)

everything in my life, down to the very bottom, so as to begin again

from the first foundations, if I wanted to establish anything firm and

lasting in the sciences.” (motivation for doubting everything)

• (Type A Doubt) “But because reason now persuades me that I

should withhold my assent no less carefully from things which are

not plainly certain and indubitable. . .”

• “Whatever I had admitted until now as most true I took in either

from the senses or through the senses; however, I noticed that they

sometimes deceived me.” [Med. I, §17-18] perception is not

reliable! Not trustworthy – the cause of many/most of our beliefs

Dream Possibility

• (Type B: the dream hypothesis) “As I consider these cases

more intently, I see so plainly that there are no definite signs

to distinguish being awake from being asleep that I am quite

astonished, and this astonishment almost convinces me that I

am sleeping.”

• Descartes is saying that there is no way to distinguish being

awake from being asleep. Therefore, everything we think we

are experiencing as real (even this class), could just be a

dream. How do we know we are not in bed dreaming about

this philosophy class? (modus tollens), if not, then we don’t

know anything.

• Reason seems to be a mental faculty that examines claims to

truth/reality in light of the degree to which doubt is possible.

This is its foundation - the critical light of doubting/reasoning

The Evil Demon

• (Type C: the evil demon) “A certain opinion has been fixed in my

mind, namely that there exists a God who is able to do anything and

by whom I have been created.”

• “God” for Descartes appears as an infinitely powerful being who

can do anything, create or deceive, according to his will. His will is

omnipotent. He could render even the propositions of logic and

mathematics false.

• But if such a God would have to be good, and therefore could not

be a deceiver, why am I sometimes deceived?

• But there might not be any God and I could be a being of mere

chance: “I would be so imperfect as to be deceived perpetually.”

[Med. I §21] his doubting extends to God = radical doubt – find a

certain foundation – not God because God could be a deceiver –the

light of reason

How to fight against deception

• So, I could be deceived on all of these matters.

• “Thus I will suppose not a supremely good God, the source of truth, but

rather an evil genius, as clever and deceitful as he is powerful, who has

directed his entire effort to misleading me.”

• “ . . . Certainly it is within my power to take care resolutely to withhold my

assent to what is false, lest this deceiver, powerful and clever as he is,

have an effect on me.” [I §23] What ‘power’ is this?

• Descartes concludes: Beliefs appropriately produced (caused) are beliefs

produced in such a way that one is unlikely to acquire beliefs in that way

unless they are true. See (ii) above. The Principle of Reliabilism as

Method produce only reliable beliefs; he cannot trust God

• “Appropriately produced” means that truth is not accidental (the case of

Smith) to how the belief was produced. The application of a method will

produce beliefs that are incorrigible – if the method is error-proof. What

kind of proposition cannot be corrected? = Foundational belief

I exist

• “And deceive me as he will, he can never bring it about that

I am nothing so long as I shall think that I am something.” [I

§25]

• “I am; I exist; this is certain. For as long as I think. Because perhaps

it could also come to pass that if I should cease from all thinking I

would then utterly cease to exist. I am therefore precisely only a

thing [res] that thinks; that is a mind, or soul, or intellect, or

reason. Now I am a true thing . . . A thing that thinks.” [I, §27]

• “But what then am I? A thing that thinks. What is that? A thing

that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and which

also imagines and senses.” [I, §28] = mental states – propositional

attitudes – the way we think about a proposition p – we can doubt

p; we can hope that p; we can think about p; we can know that p –

etc.

Knowledge Defined 3

• We can define Cartesian knowledge another way:

• S knows that p iff:

• (1) S believes p

• (2) p is true

• (3) if p were true, S would believe p

• (4) if p were not true, S would not believe p (tracking – to

follow the truth) namely, the truth to hunt an animal -

• This was proposed by Robert Nozick

• If you understand this argument, then you have understood

Descartes. I will come back to it.

Descartes’ Argument

• Meditation VI, §78

• “For this reason, from the fact that I know that I exist and that meanwhile

I judge that nothing else clearly belongs to my nature or essence except

that I am a thing that thinks, I rightly conclude that my essence consists in

this alone. Although perhaps I have a body that is very closely joined to

me, nevertheless, because on the one hand I have a clear and distinct idea

of myself – insofar as I am a thing that thinks and not an extended thing –

and because on the other hand that I have a distinct idea of a body –

insofar as it is merely an extended thing, and not a thing that thinks – it is

therefore certain that I am truly distinct from my body, and that I can

exist without it.”

• Does the conclusion really follow from the premises? Can I exist without

my body?

Sailor and Ship Analogy

• But Descartes qualifies the above conclusion at §81:

• “By means of these feelings of pain, hunger, thirst and so on, nature

also teaches that I am present to my body not merely in the way a

seaman is present to his ship, but that I am tightly joined and, so to

speak, mingled together with it, so much so that I make up one single

thing with it. For otherwise, when the body is wounded, I who am

nothing but a thing that thinks, would not sense the pain.” [§81]

• Descartes obviously has a dilemma on his hands: he has shown to his

satisfaction that mind and body are distinct substances, yet they

obvious interact in a very close (“tightly joined,” “mingled together”)

relation.

• Not only does the mind act on the body (i.e. the bodily will), but the

body acts on the mind (sensations of pain, as well as in our passions.)

Sceptical Scenarios

• A sceptical scenario is one which is

indistinguishable for you ‘from the inside’

from some current experience you have, but

in which for some reason you are radically

deceived about your environment.

• Evil Demons, Gods - Descartes

• Brains in Vats – contemporary philosophy

• The Matrix – the film

Our Epistemic Limitations about Sceptical

Scenarios

• For any proposition, H, that says that a sceptical

scenario obtains (is true), we don’t seem able to know

that it is false. Hence, we are unable to refute the

scenario.

• For by the nature of a sceptical scenario, we cannot

distinguish the situation that we are in now from a

corresponding situation in which we are radically

deceived but things seem just the same way to us. We

could be in a matrix – controlled by aliens – the

universe (not spatial) is a computer programme!

• But given that we cannot know that we are not brains-

in-vats, or being deceived by demons, how could we

possibly know that we are sitting here in a lecture?

(and so on for any other proposition that one might

think one knows.) – modus tollens: you don’t know q

unless you know not-p

The Argument from Ignorance

1. Premise: you do not know that you are not in a

sceptical scenario – not a brain in a vat

2. Premise**: But, if you do not know that you are

not in a sceptical scenario, you do not know that

you are sitting in a classroom listening to a lecture

on epistemology. [Is this true? Do you agree?] =

modus tollens (logical operation is valid)

3. Therefore, you do not know that you are sitting

here.

(and so on for any empirical proposition…)

The Closure Principle and Inference

(closure= complete a chain of inferences)

• Why is premise 2 true? “Closure” – means a process

of valid inferences…that ‘closes’ doubting.

• If S knows that p, and S knows that if p then q, then S

knows that q = modus ponens (valid)

• This seems unproblematic.

• Closure Principle. Definition: If I know that I am

sitting in my office writing a lecture, and if I know

that if I am sitting in my office writing a lecture (p),

then I am not at home drinking coffee (q), then I

know that I am not at home drinking coffee. Modus

ponens – valid inference from p.

Closure and Ignorance Putnam

• Here’s why this is relevant.

• Could you be sitting here *and* be a Brain in a Vat, deceived into thinking

you were sitting here? Logically: YES

• (possible world semantics – modal logic: there is a possible world in which I

am a brain-in-a-vat and deceived about being in a classroom – this is valid)

But some brother at lunch replies:

• “No: You know that if (p) you are sitting here eating lunch, you are not a BIV.”

[common sense response]

• So, if you did know you were sitting here, and closure holds, then given that

you know this (p), you would know that you are not a BIV (q) – common

sense and valid inference!

• If a, then b = modus pones – inference = closure

• But you do not know this. You can’t. So by modus tollens, you do not know

you are sitting here:

• If p then ¬ q -- [p = brain in a vat and q = sitting in a

classroom], then all I know is that I am a thinking but a

deceived mind (brain) and I am not sitting in a

classroom.

The Closure Principle 1

• Closure: Most of us think we can safely enlarge our

knowledge base by accepting things that are entailed (implied)

by (or logically implied by) things we know. Roughly

speaking, the set of things we know is closed under entailment

(or under deduction or logical implication), so we know that a

given claim is true upon recognizing, and accepting thereby,

that it follows from what we know. “if p, then q” modus

ponens

• Still, it seems reasonable to think that if we do know that some

proposition is true then we are in a position to know, of the

things that follow from it, that they, too, are true.

Closure Principle and Reliabilism

• ** unless the inference involves a tracking [hunting an animal – follow

the evidence being objective] procedure: my grandmother knows that I

am a wonderful grandson, but if I were not a wonderful grandson, she

would also know that.

• Tracking principle: if p is true, S believes p:

• But were p false, S would not believe p. – my grandmother still believes

[p], I am wonderful! A lack of tracking – hence no epistemic

justification!

• A closely related idea is that it is rational (justifiable) for us to believe

anything that follows from [implied/entailed] what it is rational for us to

believe [self-evident]. This idea is intimately related to the thesis that

knowledge is “closed”, since, according to some theorists, knowing p

entails justifiably believing p.

Reliabilism

• Reliabilism is an approach to epistemology that emphasizes the truth-

conduciveness [x leads to y] of a belief-forming process, method.

• F.P. Ramsey (1931), who said that a belief is knowledge if it is true, certain

and obtained by a reliable process = epistemic justification

• Fred Dretske’s “Conclusive Reasons” (1971), which proposed that S’s

belief that p qualifies as knowledge just in case S believes p because of

reasons he possesses that would not obtain unless p were true. In other

words, S’s reasons—the way an object appears to S, for example—are a

reliable indicator of the truth of p. A belief is reliable if the causal process

is reliable! Not fully tracking – because my grandmother believes her

belief has been reliably caused. -== memory – my memory is good –

about the last 10 hours – what did I do at 6 am this morning! Our

memories are reliable - but on August 20, 2012??

• See more: Zagzebski: intellectual virtues

You might also like

- MARTIN, Jean-Clet. Variations - The Philosophy of Gilles DeleuzeDocument246 pagesMARTIN, Jean-Clet. Variations - The Philosophy of Gilles DeleuzeJeezaNo ratings yet

- What Do Philosophers Do - Skepticism and The Practice of Philosophy (2017) by Penelope Maddy PDFDocument265 pagesWhat Do Philosophers Do - Skepticism and The Practice of Philosophy (2017) by Penelope Maddy PDFAnkur AroraNo ratings yet

- Outline of The Argument in Descartes's MeditationsDocument9 pagesOutline of The Argument in Descartes's MeditationsJonathan Sozek100% (1)

- Matrix and Philosophy - William Irwin, EdDocument298 pagesMatrix and Philosophy - William Irwin, Edcatalinsteliannitoi80% (5)

- Phil 102 Descartes 2Document29 pagesPhil 102 Descartes 2rhye999No ratings yet

- Expository Paper (History of Western Philosophy)Document8 pagesExpository Paper (History of Western Philosophy)maria1jennizaNo ratings yet

- Objections To Descartes' DualismDocument10 pagesObjections To Descartes' DualismAbhineet KumarNo ratings yet

- Modern Philosophy (Prof-Breur)Document10 pagesModern Philosophy (Prof-Breur)홍우람No ratings yet

- DescartesDocument23 pagesDescartesRasel Julia AlcanciaNo ratings yet

- Descartes: Doubt and CertaintyDocument17 pagesDescartes: Doubt and CertaintyTianyu TaoNo ratings yet

- PHIL 101 Week 3 Descartes Rationalist SkepticismDocument28 pagesPHIL 101 Week 3 Descartes Rationalist SkepticismtunaugurNo ratings yet

- Descartes' EpistemologyDocument21 pagesDescartes' EpistemologyMEOW41No ratings yet

- Rene Descartes' Methodic DoubtDocument7 pagesRene Descartes' Methodic DoubtKR ReborosoNo ratings yet

- Notes in Meditation Meditation 1Document5 pagesNotes in Meditation Meditation 1Amir Gabriel OrdasNo ratings yet

- Descartes' DualismDocument20 pagesDescartes' DualismNaman Thakur 20bee037No ratings yet

- DESCARTEDocument4 pagesDESCARTEPal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Descartes' MeditationsDocument4 pagesDescartes' MeditationsGlen BrionesNo ratings yet

- Reasons To Believe That The Ideas AccuratelyDocument6 pagesReasons To Believe That The Ideas Accuratelythomasfinley44No ratings yet

- Descartes Sceptical ArgumentsDocument4 pagesDescartes Sceptical Argumentslordtaeyeon76No ratings yet

- Handout Meditation 2Document5 pagesHandout Meditation 2Yoni FogelmanNo ratings yet

- Meditations On PhilosophyDocument12 pagesMeditations On PhilosophyButch CabayloNo ratings yet

- Descartes and Rationalism - RecentDocument36 pagesDescartes and Rationalism - RecentjohnNo ratings yet

- PHIL 1050 (Andrew Bailey) - Replacement Essay For MidtermDocument10 pagesPHIL 1050 (Andrew Bailey) - Replacement Essay For MidtermNanziba IbnatNo ratings yet

- Descartes Meditations Doubt EverythingDocument13 pagesDescartes Meditations Doubt Everythingsikandar aNo ratings yet

- Descartes MeditationsDocument9 pagesDescartes MeditationsJustin Nyang'orNo ratings yet

- What Is MetaphysicsDocument24 pagesWhat Is MetaphysicsDiane EnopiaNo ratings yet

- 3-Descartes' Meditations One and Two-1Document17 pages3-Descartes' Meditations One and Two-1Noora MojaddediNo ratings yet

- Descartes and His Immanentistic Effect To Cause Demonstration of The Existence of GodDocument66 pagesDescartes and His Immanentistic Effect To Cause Demonstration of The Existence of GodPaul HorriganNo ratings yet

- Phil101 3Document20 pagesPhil101 3Faruk AlanNo ratings yet

- 1 DescartesDocument20 pages1 DescartesangrolloNo ratings yet

- Priori KnowledgeDocument12 pagesPriori KnowledgeHasham RazaNo ratings yet

- The Full Interview Alan WattsDocument17 pagesThe Full Interview Alan Wattschristianmartinet320No ratings yet

- MODERN PHILOSOPHY QUIZ Nov 11Document5 pagesMODERN PHILOSOPHY QUIZ Nov 11Kris Angela Dugayo PasaolNo ratings yet

- History of Modern Philosophy (Notes)Document31 pagesHistory of Modern Philosophy (Notes)TrenyNo ratings yet

- Jacob Needleman - The Great Unknown Is Me, Myself (Parabola Interview)Document17 pagesJacob Needleman - The Great Unknown Is Me, Myself (Parabola Interview)Kenneth AndersonNo ratings yet

- Descartes's Meditations On First Philosophy: G. J. Mattey Winter, 2006 / Philosophy 1Document12 pagesDescartes's Meditations On First Philosophy: G. J. Mattey Winter, 2006 / Philosophy 1rikimaru13No ratings yet

- Descartesslides13 HoDocument13 pagesDescartesslides13 HoAnonymous u80JzlozSDNo ratings yet

- 3 - 4 Philosophy NotesDocument52 pages3 - 4 Philosophy NotesCindy LiuNo ratings yet

- Looking Between The Cracks: Exploring the Unseen Details of the Maltese TemplesFrom EverandLooking Between The Cracks: Exploring the Unseen Details of the Maltese TemplesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Descartes' Evil Demon Keith CromeDocument8 pagesDescartes' Evil Demon Keith Cromej9z83fNo ratings yet

- Descartes' Rationalism: Rational IntuitionDocument4 pagesDescartes' Rationalism: Rational IntuitionTrung TungNo ratings yet

- Descartes NotesDocument2 pagesDescartes NotesCindy LiuNo ratings yet

- SkepticismDocument36 pagesSkepticismkennethNo ratings yet

- RationalismDocument22 pagesRationalismHabib UllahNo ratings yet

- Descartes Meditations OutlineDocument6 pagesDescartes Meditations OutlineJae AkiNo ratings yet

- 01 Descartes NotesDocument18 pages01 Descartes NotesBoram LeeNo ratings yet

- Psych 101Document50 pagesPsych 101Mary Joy CamposNo ratings yet

- René Descartes: Meditations On First PhilosophyDocument68 pagesRené Descartes: Meditations On First Philosophymaximil_kolbe3258No ratings yet

- DescartesDocument2 pagesDescartesjoseph baporaNo ratings yet

- Solipsism and NietzscheDocument6 pagesSolipsism and NietzscheMohamed1994No ratings yet

- Is An Unknowable God Logical?Document82 pagesIs An Unknowable God Logical?BaquiaNo ratings yet

- Austin Osman Spare - Book of PleasureDocument27 pagesAustin Osman Spare - Book of PleasureIsaac Christou100% (1)

- The Limits of KnowledgeDocument16 pagesThe Limits of KnowledgeEliam WeinstockNo ratings yet

- Rene Descartes' Methodic SkepticismDocument5 pagesRene Descartes' Methodic Skepticismmichael jhon amisola100% (1)

- Rene DescartesDocument5 pagesRene Descartesmichael jhon amisolaNo ratings yet

- Brain in A VatDocument5 pagesBrain in A VatRamzi H. KawaNo ratings yet

- Descartes - Introductory NotesDocument5 pagesDescartes - Introductory NotesBoram LeeNo ratings yet

- I Think Therefore I AmDocument5 pagesI Think Therefore I AmAditi SinghNo ratings yet

- Theory of Knowledge and Unique Contributions of PhilosophersDocument58 pagesTheory of Knowledge and Unique Contributions of PhilosophersEdward Haze DayagNo ratings yet

- Personal Notes From Conversations W-Seth by Susan WatkinsDocument6 pagesPersonal Notes From Conversations W-Seth by Susan WatkinspacificsunsetNo ratings yet

- Descartes Meditation NotesDocument8 pagesDescartes Meditation NotesNavid JMNo ratings yet

- 1 The Challenge of ScepticismDocument45 pages1 The Challenge of Scepticismjafle567No ratings yet

- Essay About JournalismDocument7 pagesEssay About Journalismb6yf8tcd100% (2)

- Descartes Finitude of Evil Genius Kennington OCR PDFDocument7 pagesDescartes Finitude of Evil Genius Kennington OCR PDFJohannesClimacusNo ratings yet

- Discussion and Criticism of Cartesian EpistemologyDocument65 pagesDiscussion and Criticism of Cartesian EpistemologyStephen AlaoNo ratings yet

- VinciDocument245 pagesVincianimalismsNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Epistemology - TaylorDocument16 pagesOvercoming Epistemology - Taylorsmac226100% (1)

- Atheism or AgnotheismDocument5 pagesAtheism or AgnotheismAliasger SaifuddinNo ratings yet

- Dream-Stanford EncyclopediaDocument37 pagesDream-Stanford EncyclopedianooriaanNo ratings yet

- History of Modern Philosophy (Notes)Document31 pagesHistory of Modern Philosophy (Notes)TrenyNo ratings yet

- The Matrix - The Philosophy Behind The MovieDocument58 pagesThe Matrix - The Philosophy Behind The Movieparmenide00100% (1)

- Al-Ghazali and Descartes From Doubt To Certainty: A Phenomenological ApproachDocument21 pagesAl-Ghazali and Descartes From Doubt To Certainty: A Phenomenological ApproachD BNo ratings yet

- Pierre Klossowski - The BaphometDocument220 pagesPierre Klossowski - The BaphometDuarte MartinhoNo ratings yet

- VrbookbigDocument428 pagesVrbookbigphanthanhhungNo ratings yet

- The First Meditation: John CarrieroDocument27 pagesThe First Meditation: John CarrieroRafael SerraNo ratings yet

- DescartesDocument5 pagesDescartessparshikaaNo ratings yet

- RENE DESCARTES - Philosophize This TranscriptDocument21 pagesRENE DESCARTES - Philosophize This TranscriptButch CabayloNo ratings yet

- Aristotle and DescartesDocument13 pagesAristotle and Descartesbella hackett0% (1)

- Philosophy NotesDocument28 pagesPhilosophy NotesFilippo NerviNo ratings yet

- DESCARTEDocument4 pagesDESCARTEPal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Bjornstad, Ibbett - Walter Benjamin's Hypothetical French TrauerspielDocument175 pagesBjornstad, Ibbett - Walter Benjamin's Hypothetical French TrauerspielJoãoCamilloPennaNo ratings yet

- Descartes NotesDocument2 pagesDescartes NotesCindy LiuNo ratings yet

- Descartes PDFDocument4 pagesDescartes PDFForrest BristowNo ratings yet

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Dreams and DreamingDocument37 pagesStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Dreams and DreamingGeorgia StellinNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Critical Guides) Karen Detlefsen - Descartes' Meditations - A Critical Guide-Cambridge University Press (2012) PDFDocument278 pages(Cambridge Critical Guides) Karen Detlefsen - Descartes' Meditations - A Critical Guide-Cambridge University Press (2012) PDFCarolina Mircin0% (1)

- Rene Descartes & OthelloDocument4 pagesRene Descartes & OthelloRuihong ZhangNo ratings yet

- PHIL 1050 (Andrew Bailey) - Replacement Essay For MidtermDocument10 pagesPHIL 1050 (Andrew Bailey) - Replacement Essay For MidtermNanziba IbnatNo ratings yet

- Atheism and Radical Skepticism Ibn Taymiyyahs Epistemic CritiqueDocument52 pagesAtheism and Radical Skepticism Ibn Taymiyyahs Epistemic CritiqueZaky MuzaffarNo ratings yet

- 50 Philosophy Ideas Ben DurpeDocument208 pages50 Philosophy Ideas Ben DurpeArjun Rathore100% (6)